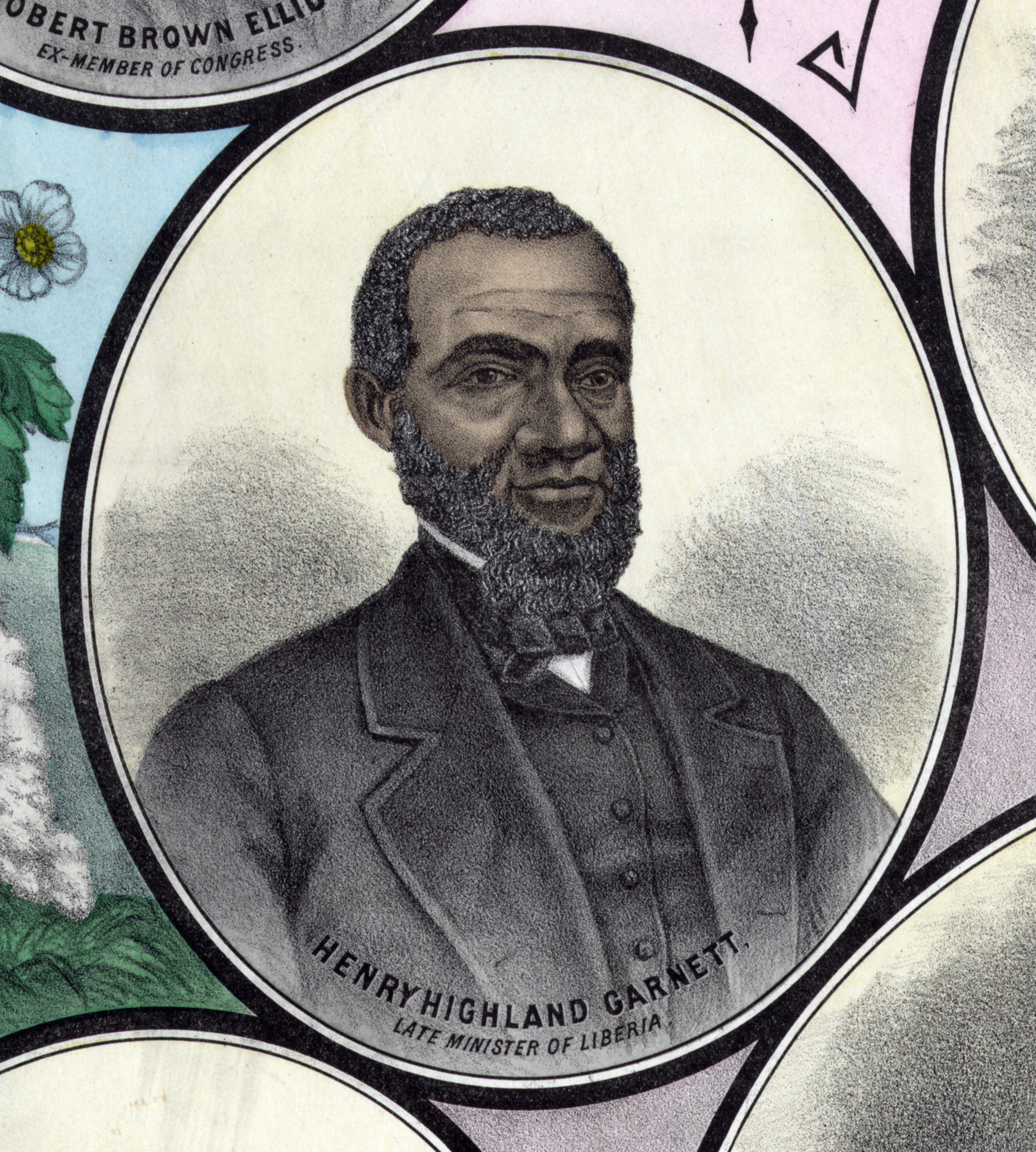

Today, the Reverend Dr. Henry Highland Garnet is the most famous African American you never learned about during Black History Month. In the 19th century however, Garnet, who lived from 1815 to 1882, was recognized as one of the foremost anti-slavery organizers in the world. He was the founding president of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, an organization that waged international campaigns against human trafficking and Cuban patriot José Martí called him America’s “Moses.”

And, though he is often left out of the popular story of abolition, Rev. Garnet’s work of building bridges of solidarity offers a unique perspective on what it means for the U.S. to value human rights in an international context in the 21st century.

Born a slave in Maryland, Garnet was carried by his parents to freedom in the North at the age of 9. As a teenager, Garnet attended Noyes Academy in New Hampshire, an integrated institution of higher learning founded by anti-slavery advocates. Suffering from an ailment that would eventually cost him his leg, the enterprising student discovered one day that area white farmers were plotting to destroy the school. Garnet’s biographer noted that he “spent most of the day in casting bullets in anticipation of the attack, and when the whites finally came he replied to their fire with a double-barreled shot-gun, blazing from his window, and soon drove the cowards away.” Though the mob eventually destroyed the school, Garnet’s covering fire allowed his fellow students to escape under the cover of darkness.

Rev. Garnet’s speeches on slavery and liberation captivated audiences. At the National Negro Convention held in Buffalo in 1843, the 27-year-old minister came forward with an audacious plan to end slavery, urging an armed uprising of the slaves. “If you would be free in this generation, here is your only hope,” he said. “However much you and all of us may desire it, there is not much hope of redemption without the shedding of blood. If you must bleed, let it all come at once—rather die freemen, than live to be slaves.”

Garnet came to this radical conclusion because he believed that it was the only way to stop the United States from spreading slavery via warfare across the continent: “The Pharaohs are on both sides of the blood red waters!” Rev. Garnet lectured. “You cannot move en masse, to the dominions of the British Queen—nor can you pass through Florida and overrun Texas, and at last find peace in Mexico. The propagators of American slavery are spending their blood and treasure, that they may plant the black flag in the heart of Mexico and riot in the halls of the Montezumas.”

Garnet interpreted the contested U.S. invasion of Mexico that launched the Mexican-American War in 1846 as a diabolical plan to re-plant slavery’s banner in a republic that had effectively abolished chattel bondage. In contrast to those politicians who preached the hatred of Mexicans, Garnet reminded Americans that fugitive slaves regularly found sanctuary in Mexico. Garnet lauded the Mexican people as “liberty-loving brethren,” and “ultra-abolitionists.” Garnet’s understanding of the role that Mexican and Latin American abolitionists played in the global struggle against slavery informed his later human-rights crusades.

After helping to recruit black soldiers to the Union Army during the Civil War—and barely escaping a vengeful white mob during the New York Draft Riots of 1863—Garnet became the first African American to deliver a sermon to the United States Congress. On Feb. 12, 1865, Rev. Garnet urged Congress to formally adopt the 13th Amendment, saying, “If slavery has been destroyed merely from necessity, let every class be enfranchised at the dictation of justice. Then we shall have a Constitution that shall be reverenced by all, rulers who shall be honored and revered, and a Union that shall be sincerely loved by a brave and patriotic people, and which can never be severed.”

At the end of the Civil War, Henry Garnet expressed his disappointment at what he considered to be premature celebrations of the end of slavery. Rev. Garnet urged abolitionists to retool their anti-slavery organizations to fight slavery’s continuing existence in nations such as Cuba and Brazil. At the height of Reconstruction, Garnet insisted that African Americans tie their struggles for the passage of equal-rights legislation with the Cuban liberation struggle against Spanish rule. In 1872, the popular minister helped to organize the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee, which formed branches throughout Florida, Louisiana, New York, California and other states. The committee launched a national movement to demand that the United States extend support to the Cuban patriots fighting for independence from the Spanish Empire.

At a mass meeting held in Philadelphia in 1877, Rev. Garnet expounded on the theme that the work of slavery abolitionism was incomplete. “If the veteran abolitionists of the United States had not mustered themselves out of service,” he argued, “I believe that there would not now have been a single slave in the Island of Cuba.” Rev. Garnet continued, “We sympathize with the patriot of Cuba not simply because they are Republicans, but because their triumph will be the destruction of slavery in that land.” Cuban liberation leaders, including the great general Antonio Maceo, met with Garnet and other African American activists to form an international coalition that dramatically expanded the meaning of emancipation.

Before a standing-room only memorial service held at the Great Hall of the Cooper Union in New York City, Garnet’s compatriots in the Anti-Slavery Society observed, “Having personally experienced the woes of the down-trodden of his race, he seemed all the better fitted to sympathize with the down-trodden and afflicted in every clime…”

And yet the strength and breadth of Garnet’s advocacy helped contribute to his later obscurity. His urgings of insurrection before the war had frightened the mainstream of the abolitionist movement. And later, American historians tended focus on domestic issues during the Reconstruction period, viewing that time as a “national event,” rather than the international solidarity work he did. That view has led many to miss the way Garnet connected African American citizenship with the emancipation of people in other nations, and to gloss over the role he played.

Today, when the President of the United States dismisses countries in Africa as well as Haiti and El Salvador, and when politicians often seek to divide us from each other and the world, it’s time to remember Henry Highland Garnet’s life — and what it looks like to stand on the side of the oppressed, not only at home but all over the world.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Paul Ortiz is the author of the new book An African American and Latinx History of the United States, available now from Beacon Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com