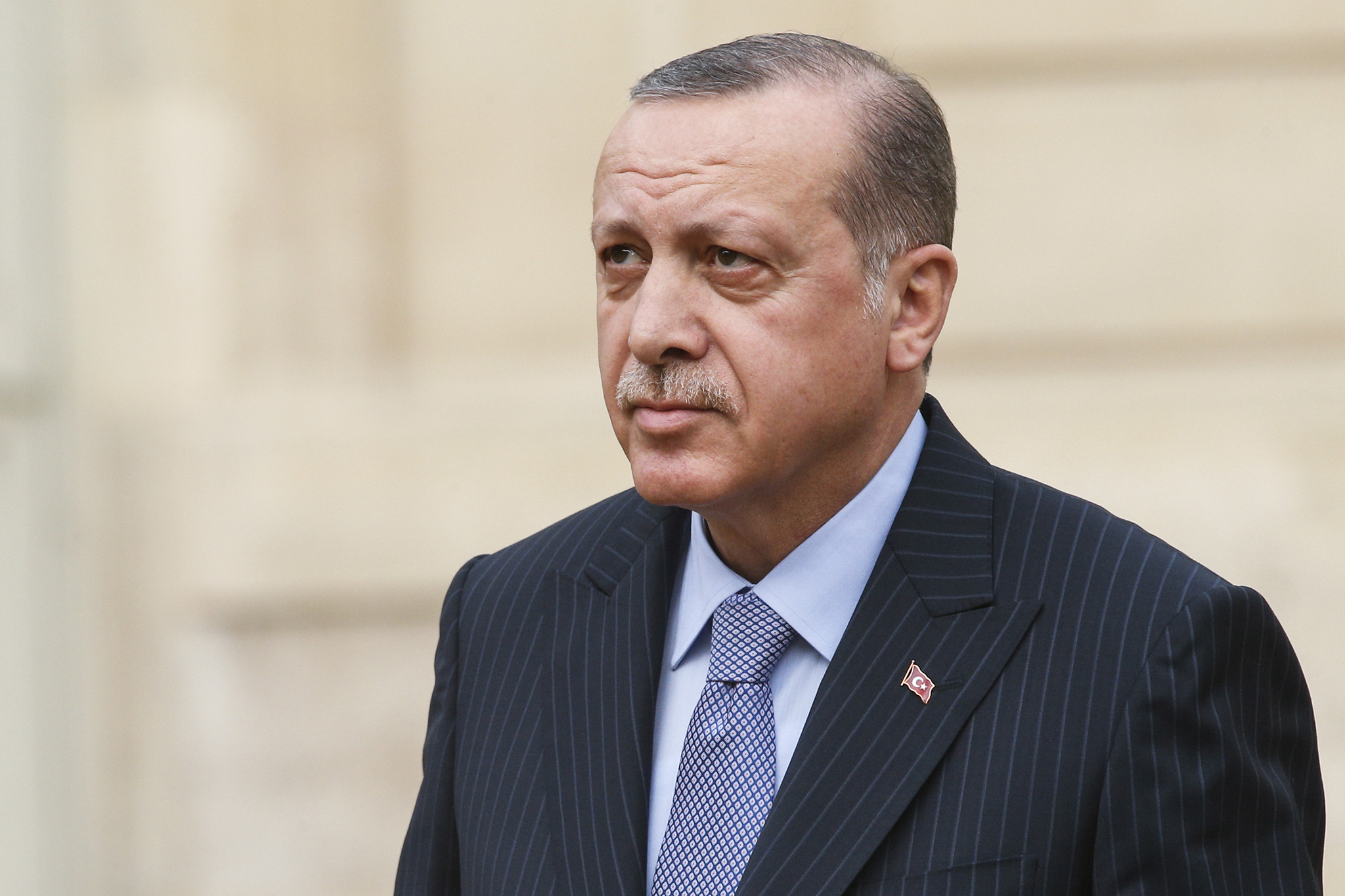

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan isn’t happy with the West. He’s angry at the Trump Administration, because it refuses to extradite Fethullah Gulen, a former preacher now living in Pennsylvania whom Erdogan accuses of treachery and treason. He is also infuriated by the fact that the U.S. has chosen to partner with Syrian Kurds in the fight against ISIS, because he sees them as terrorists who support Kurdish separatists inside Turkey. He has demanded that the U.S. stop working with Syrian Kurds, but that won’t happen anytime soon. Erdogan also has a gripe with Europe, which has condemned his human-rights record and refused to advance Turkey’s bid to join the E.U.

All ambitious leaders need allies, and Erdogan has turned to Russian President Vladimir Putin, who is only too happy to help undermine NATO by courting one of its most strategically important members. In November, Erdogan thumbed his nose at Western critics by purchasing a Russian-made air-defense system while scolding NATO allies for not offering him a better deal.

Erdogan is not likely to find Russia a reliable friend. In 2013, after his repeated warnings that Russian planes should not violate Turkey’s airspace en route to Syria, Turkey shot down a Russian jet, killing a pilot. Putin responded by squeezing Turkey’s economy until Erdogan finally apologized. The pair now treat that episode as old history, but it shows what can happen when these two strong-willed leaders are at cross-purposes in Syria, the place where their interests are most clearly at odds. Erdogan wants Syria’s Bashar Assad out. Russia considers Assad its most important Middle East ally.

And now Turkey has launched a ground assault in Syria, one that’s intended to push Syrian Kurds from territory they hold near the Turkish border. The U.S. and Russia have both urged restraint and, for now, have pulled their forces from Turkey’s path. But both have worked with Syria’s Kurds and would prefer that Turkey back off. Erdogan insists he will not. Russian objections have been muted, but that may not last long.

Turkey will remain a member of NATO, because neither Turkey nor the alliance have good reason to cut ties. But Erdogan’s relations with Europe and the U.S. will worsen as Turkey moves toward probable early elections later this year and he turns to anti-Western rhetoric to shore up his base. He has already angered Iran, which also considers Assad a crucial ally, and the Saudis over his support for Islamist political movements in the Arab world.

That leaves Russia. But Erdogan needs Putin much more than Putin needs Erdogan–and he had better be careful.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com