Photographer Camilo José Vergara has spent his career photographing the poorest and most segregated communities in urban America. As part of this work, Vergara has spent the last 30 years documenting murals and signs, many of them including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in cities across the U.S. Vergara’s unique visual record draws distinct categories of how Dr. King’s likeness appears in these hand-painted tributes: as the “everyman,” a mythic figure, defaced, with company in African American and Latino pantheons and, since 2009, alongside President Barack Obama. Here, Vergara writes for LightBox about the role these images play in American culture.

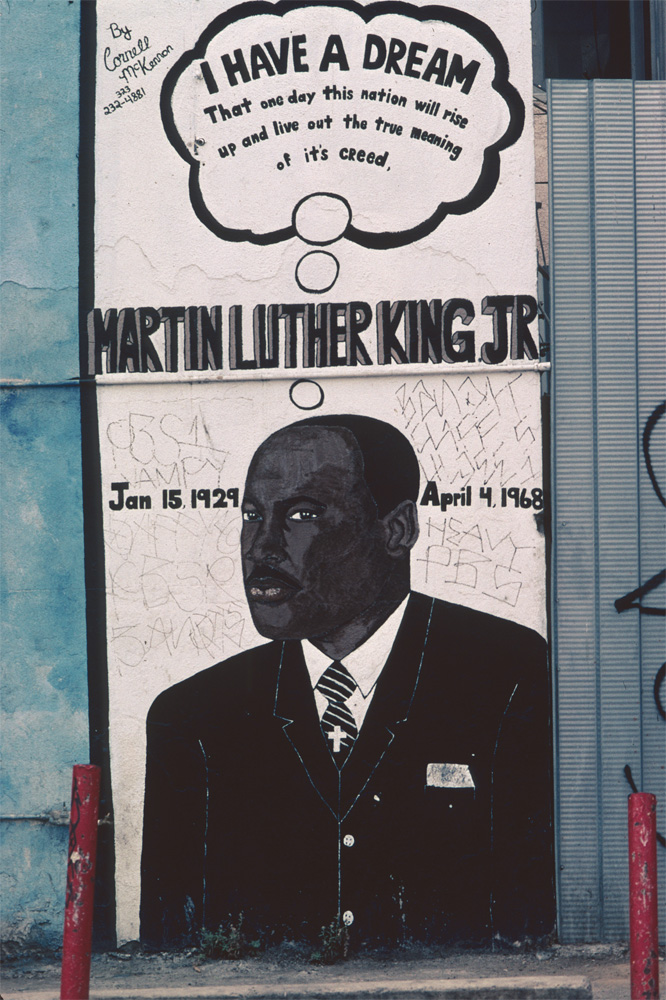

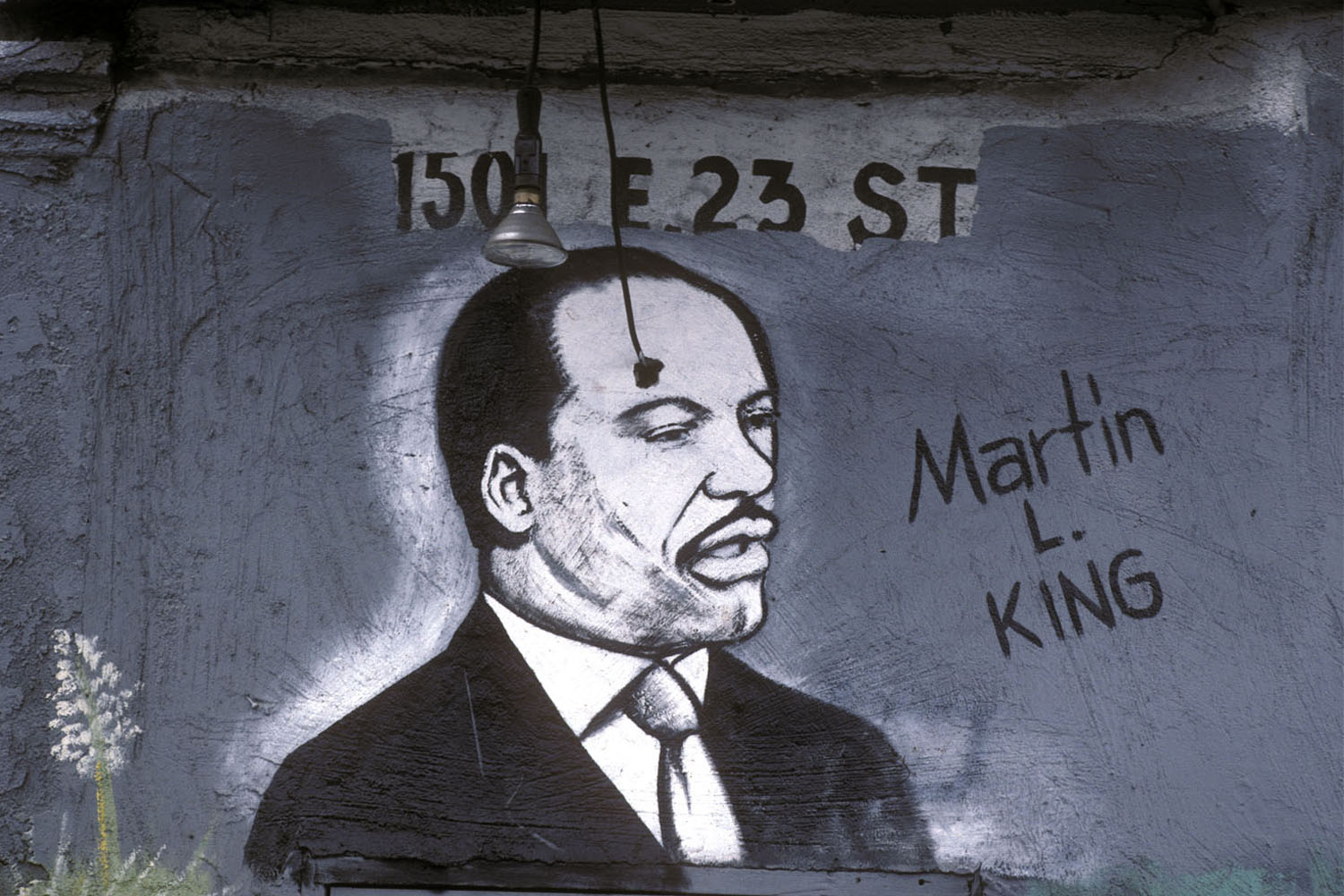

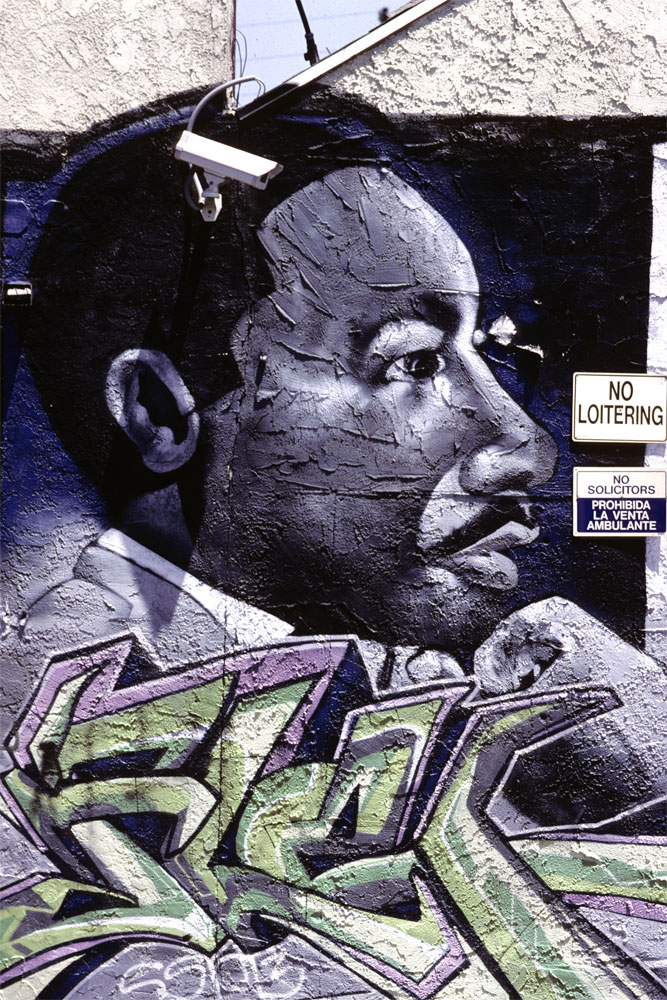

In America’s inner cities, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is a popular subject of street art. Since the 1970’s, I have documented many of these hand-painted images of Dr. King along the streets and alleys of cities from New York and Los Angeles to Chicago and Detroit. Portraits of the slain civil rights leader appear on liquor stores, barbershops and fast food restaurants. Often Dr. King’s famous pronouncement, “I have a dream,” accompanies his image on the wall.

I didn’t set out to intentionally document murals and signs—rather, I found one and photographed it, then another, and soon I had a unique, well defined collection of images of Dr. King. And in talking to artists and storekeepers, I learned that these folk images expressed the way inner-city residents saw him.

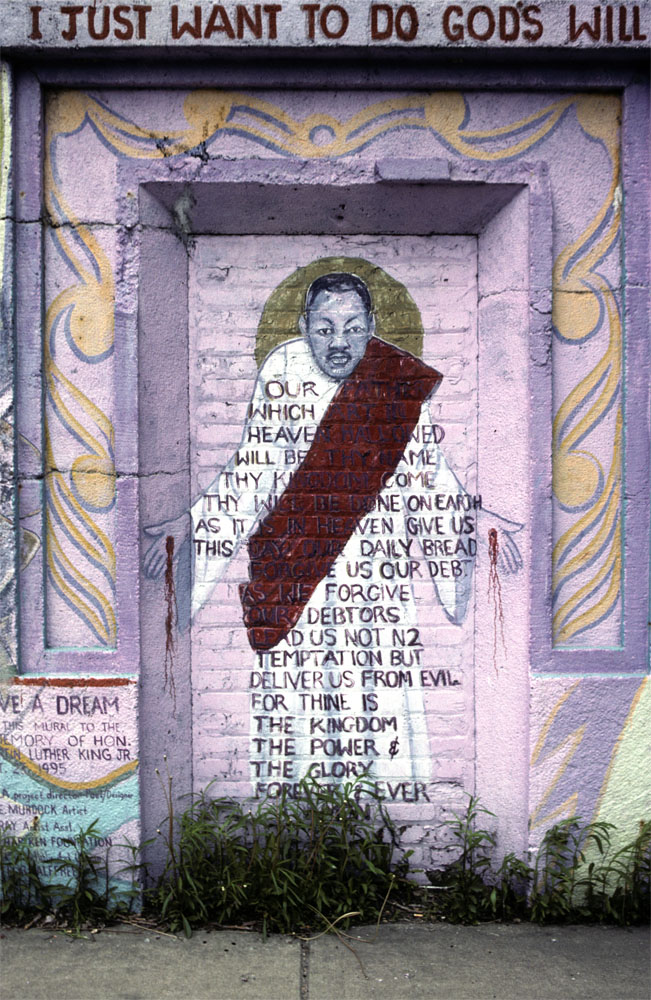

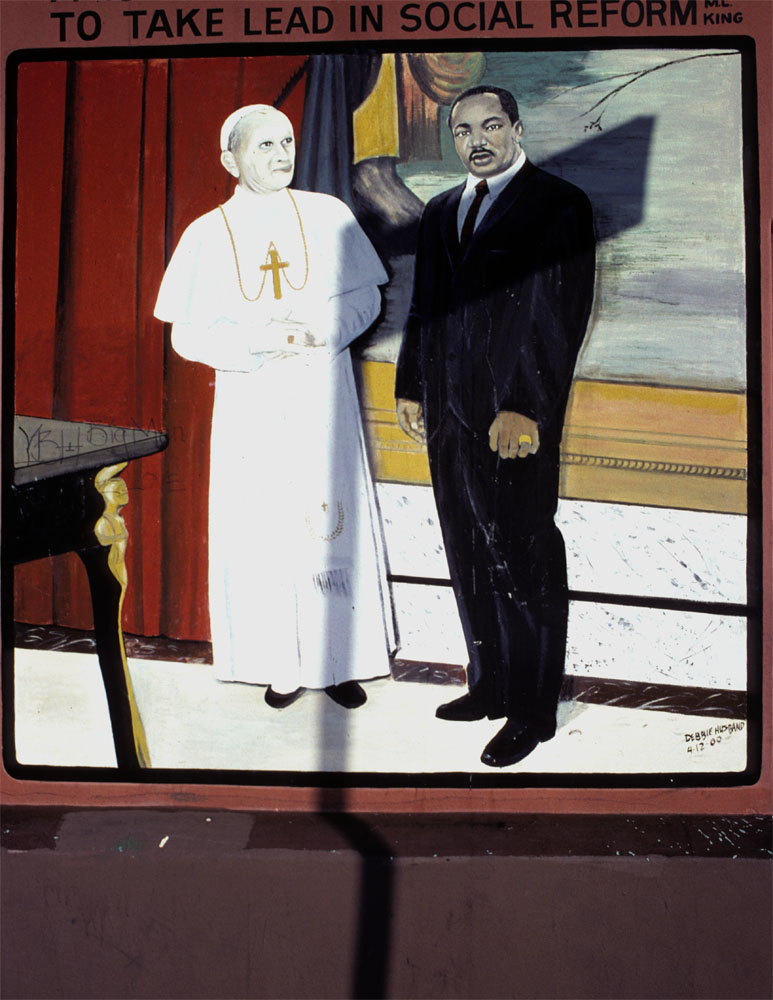

On the streets, Dr. King is represented in many ways–sometimes a statesman, other times a visionary, hero or martyr. Some paintings show Dr. King proud and thoughtful with his hand under his chin, while in others he looks friendly and compassionate, arms outstretched.

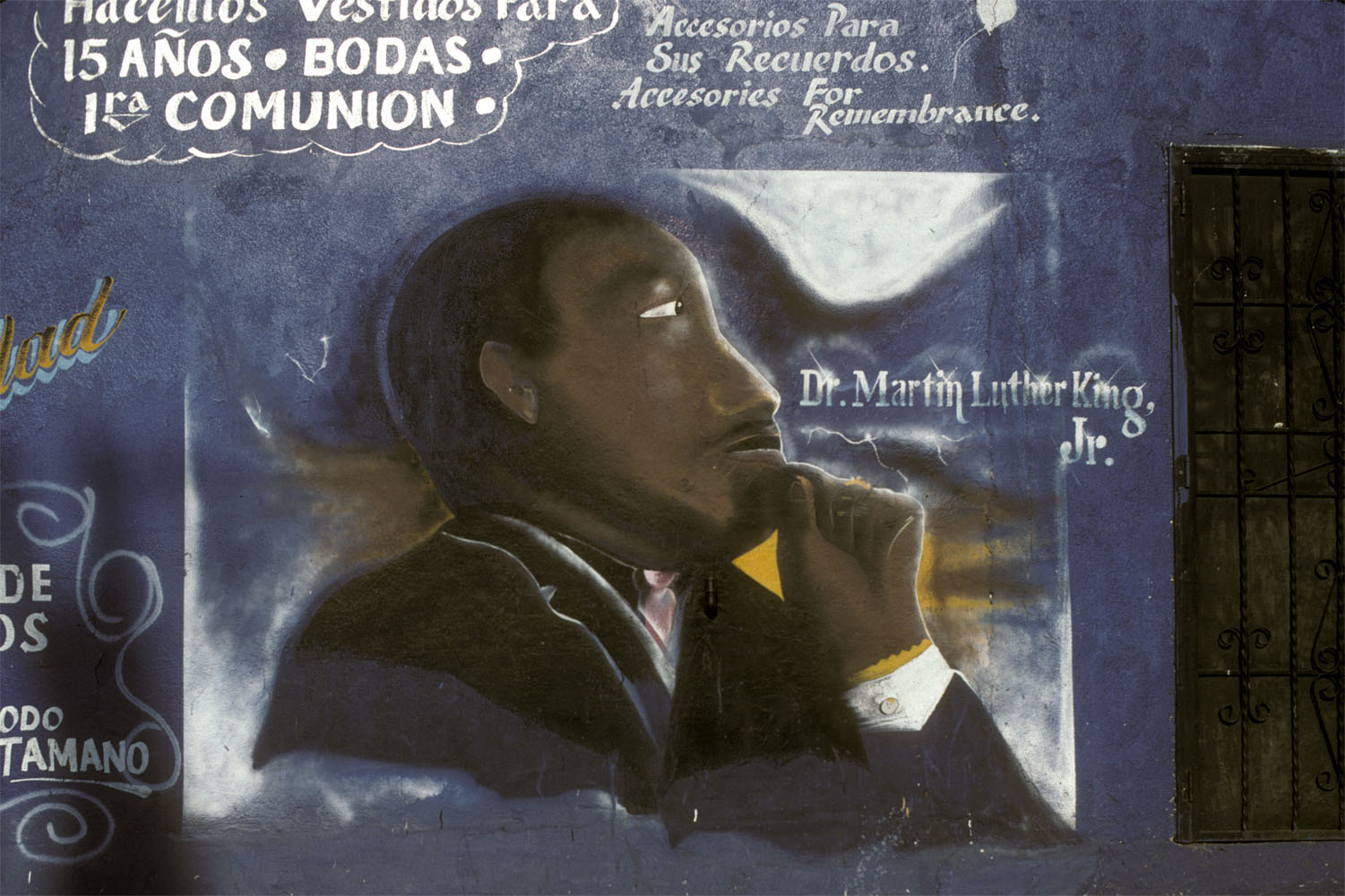

The sign painters and amateur artists who create these portraits use iconic photographs of Dr. King to model their subject. However, they often fall short of producing a perfect likeness. It is not uncommon for Dr. King to look Latino, Native American or Asian.

These portraits of Dr. King serve many purposes – from selling merchandise to encouraging a sense of security, identity and pride in poor communities. In Los Angeles, after the riots in 1992, many Latino shopkeepers painted Dr. King’s portrait on the façades of their businesses in the hope of deterring rioters.

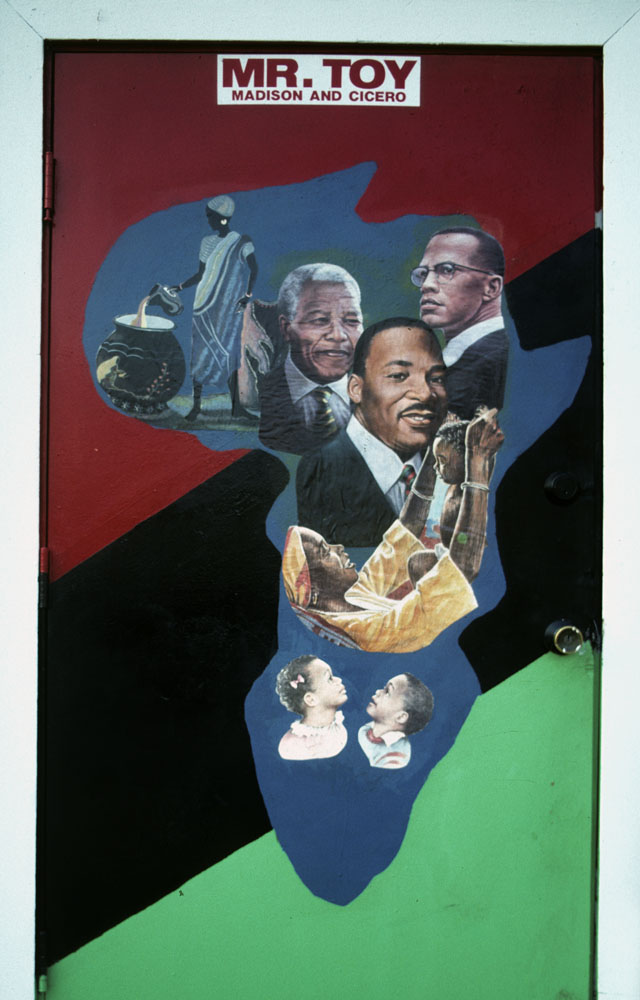

In Black neighborhoods, portraits of Dr. King rarely include Caucasian or Latino figures. Rather, Dr. King is often accompanied by icons such as Malcolm X, who represents the embodiment of righteous anger, or other Black leaders such as Nelson Mandela, Harriet Tubman or Rosa Parks. And while Dr. King continues to be a popular icon, portraits of Malcolm X and Nelson Mandela have been steadily declining.

In group portraits, Dr. King takes center stage, often appearing physically larger than the rest. Since 2009, Dr. King has been painted with President Obama, a local resident explained the pairing saying: “Rosa Parks sat so Martin Luther King could walk. Martin Luther King walked so Obama could run. Obama ran so we can all fly.”

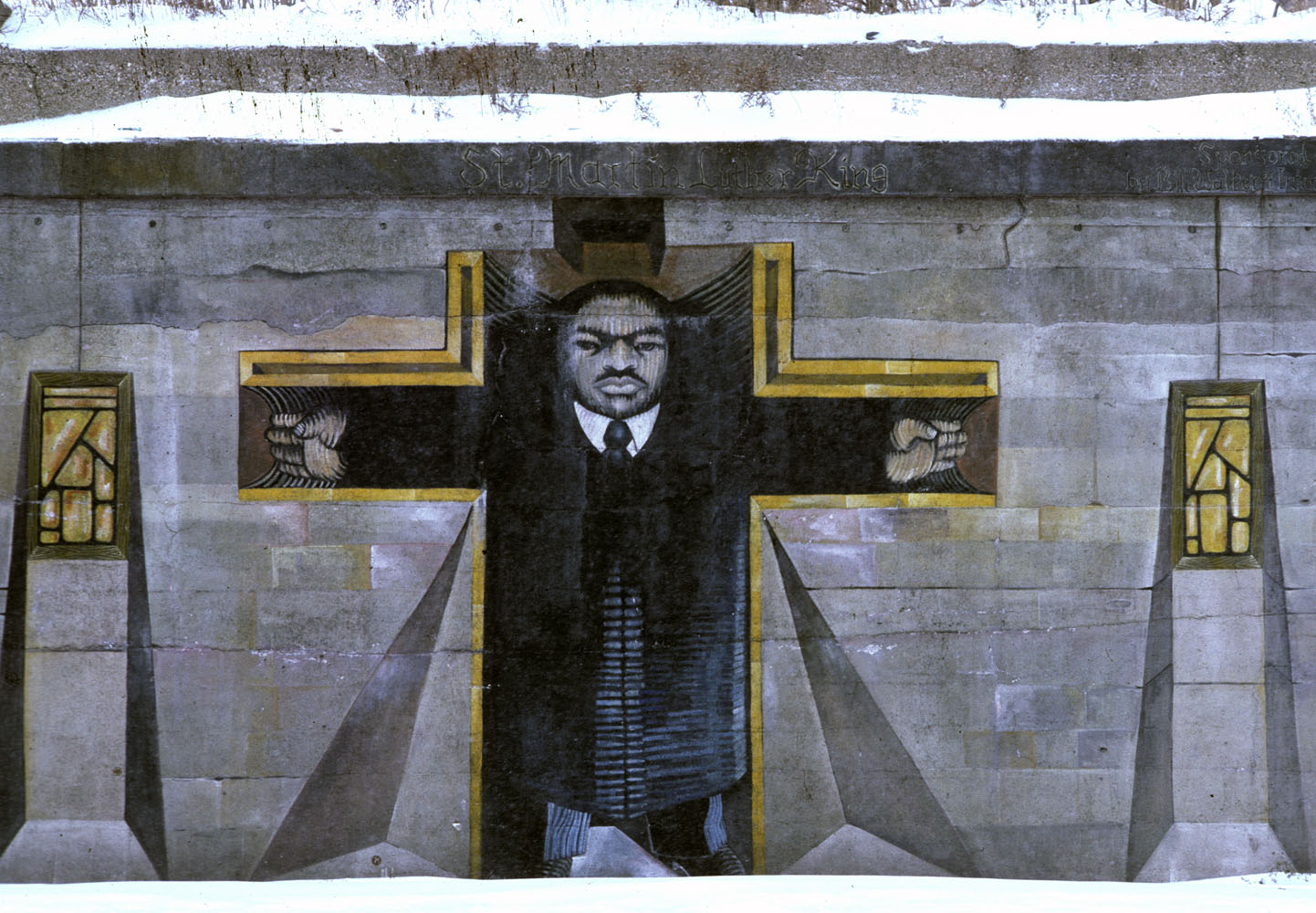

In Latino neighborhoods, figures such as Pancho Villa, Benito Juarez and the Virgin of Guadalupe appear with Dr. King. In Detroit, among the ruins of what once was the city’s Chinatown, I found a memorial mural to Vincent Chin, a Chinese American auto-worker who was the victim of a race-motivated murder, in it Dr. King had Asian features. On a viaduct in Chicago’s South Side, I discovered a mural by the artist B. Walker that depicted Dr. King as a crucified saint. Clearly influenced by the Mexican muralist tradition, Walker painted Dr. King with pronounced Mexican-Indian features.

Most murals and street portraits of Dr. King are ephemeral. Paint fades, businesses change hands and neighborhood demographics shift. Gradually, images reflecting the culture and values of poor communities are lost. Folk art museums collect objects, but seldom photographs. Museums, if they collect murals at all, are typically interested in commissioned works by professional artists. Often, my photographs are the only lasting record of these public works of art.

It is ironic that given Dr. King’s life-long struggle against segregation and poverty, his name and likeness have become one of the defining visual elements of the American ghetto, a place he worked his whole life to abolish. His dream of justice and equality for all seems as distant today, if not more so, than when he was alive.

I love the street images of Dr. King in all their earnest misrepresentations because of the hopes they embody. As I find and photograph them on my urban explorations, I am happy building my own Smithsonian—a permanent record of historical work on subject matter which is often overlooked, and without cataloguing, would otherwise be lost.

It is my strong belief that portraits such as these are rare and should have been part of the American memory, but it bothered me that they hadn’t been—a fact that is changing: On Jan. 18, the New York Historical Society is slated to open an exhibition of these images to celebrate what would have been Dr. King’s 84th birthday. After the closing of the exhibition, the photographs will become part of their permanent collection.

Camilo José Vergara is a 2002 MacArthur fellow whose books include American Ruins and How the Other Half Worships. You can see more of his photos on his web site and can contact him at camilojosev@gmail.com.

An exhibition of Vergara’s MLK photographs is on display at the New York Historical Society through May 5, 2013.

All photos courtesy Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, Calif.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com