Days after President Trump personally pushed allies to pressure Congress to repeal a tax law prohibiting churches and tax-exempt institutions from political organizing in its upcoming tax bill, the Senate parliamentarian blocked language for the change on Thursday night.

On Monday, Trump invited his cadre of religious supporters in the Oval Office where they gave him an award following his plan to move the U.S. Israel embassy to Jerusalem. Ralph Reed, founder of the Faith and Freedom Coalition, spoke with Trump about the fate of the half-century-old law called the Johnson Amendment.

“‘We are totally for this, we are 100% on board, but they need to hear from you, these conferees need to hear from you,’” Reed recounts Trump telling him, referencing the bill’s conference committee members, who are hammering out the differences between the Senate and House versions of the tax bill.

Trump reminded Reed that he had signed an executive order in May relaxing prohibitions on political organizing by religious groups. But since Congress determines any actual change to the law, Trump expressed concern that a future Democratic administration could just as easily roll back his executive orders, as he has done with Obama’s.

Reed walked out of the Oval and called his field and legislative teams. “Turn the phones on,” he told them.

Faith and Freedom targeted each conferee’s office with hundreds of phone calls. They also enlisted support from individuals close to the members. “We had megachurch pastors and leading businessmen reaching out to them, in private meetings, and regular phone calls, in texts,” Reed says. “We left it all on the field.”

Reed says he was confident they had the votes to include the language in the conference committee’s version of the tax bill. But because the Senate is using a special budgetary procedure to try to pass the tax bill, the Senate parliamentarian must rule that every part of the bill has a budgetary effect. Thursday night, she ruled that the repeal of the Johnson Amendment did not qualify.

“We always knew that this was a danger,” Reed says of the decision, which he describes as “erroneous and dead wrong.”

“We are exploring various options for a workaround,” he says.

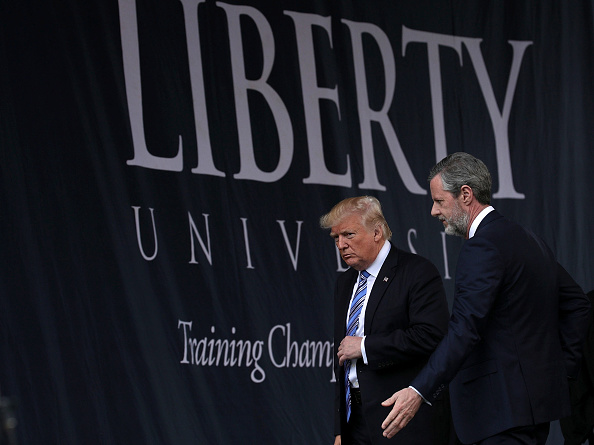

Trump also raised the issue of the Johnson Amendment with Liberty University president and early Trump endorser, Jerry Falwell Jr., at a White House Christmas party earlier this week.

“One of the first things he brought up was the Johnson Amendment,” Falwell says of his private conversation with Trump, who visited with Falwell and his wife, Becki Falwell, in the White House residence. “He’s got to get some of his people, me included, to deal with this concern that charities would become backdoor ways to donate to political campaigns.”

Falwell blames Trump’s evangelical advisors for not addressing that concern. He suggests there be a limit to how much nonprofits could spend on lobbying or supporting a political candidate, perhaps pegged to a percentage of their gross revenue. “Maybe 5% or less,” Falwell says.

“If Liberty has $1.5 billion in reserves, there would be a problem if we were allowed to use that to support a political candidate,” he says. “We have to work that out.”

Critics of the repeal have long expressed concern that it would create a campaign finance loophole for tax-exempt institutions. “The provision would have allowed partisan campaign activity to permeate tax-exempt organizations, transforming them from charitable entities into quasi-campaign groups,” says Maggie Garrett, legislative director for Americans United. “People could have donated money to a church or charity and claimed a tax deduction for it, even if that money were used to promote or attack a candidate.”

Falwell’s suggestion could likely open the door to increased government inspection of church books, a move unlikely to have much support among those who think their First Amendment rights to religious freedom are already overly scrutinized. Execution and compliance could be a headache for small nonprofit groups and the Internal Revenue Service alike.

Falwell remains confident that Trump is committed to ending the prohibition on political organizing by churches and other nonprofits. “Until the President gets a Senate of real Republicans, he won’t be able to make the changes he wants to make,” he says.

Last year shortly before the Republican nominating convention in Cleveland, Trump called Falwell to personally tell him that the 2016 Republican Party platform would include the repeal of Johnson Amendment. “He thinks it is going to be a revolution in the Christian world,” Falwell told TIME last summer.

Social conservatives, and in particular Trump’s white evangelical supporters, have long advocated for the repeal of the Johnson Amendment. This year the effort has been one of their top policy priorities, along with nominating a conservative justice to the Supreme Court, repealing the Affordable Care Act, defunding Planned Parenthood and moving the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. At the end of Trump’s first year in office, one of those five goals has been fully realized, and the second — moving the embassy — has been announced but is expected to take years to enact.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com