This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

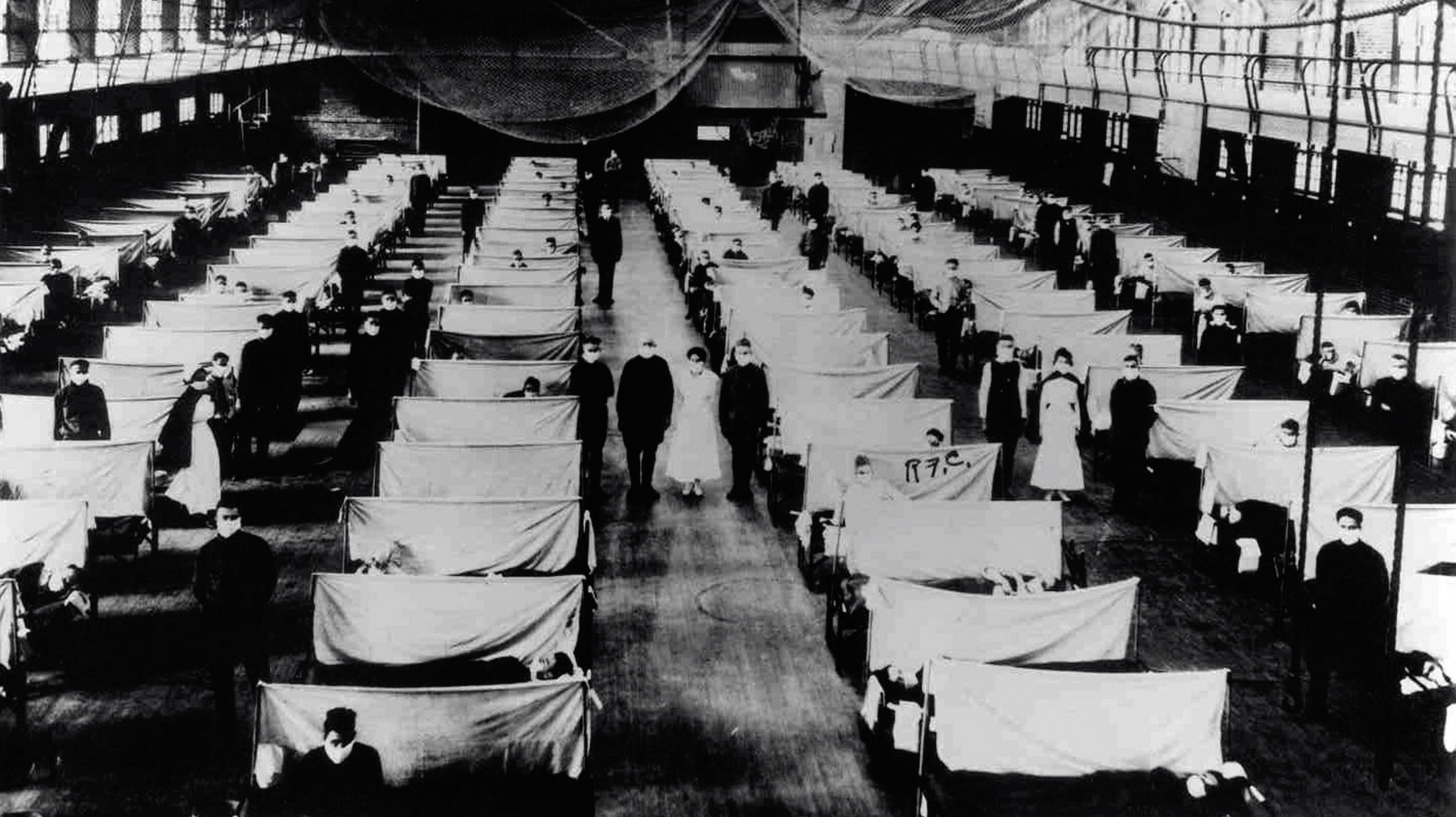

Next year, 2018, marks the centenary of the beginning of the so-called “Spanish” flu. The pandemic killed between 50 and 100 million people, meaning that in terms of loss of life it dwarfed the First World War (around 17 million dead), possibly also the Second World War (around 60 million dead), and perhaps even both together. Yet there are no monuments to the victims of the pandemic, no cenotaph in London, Moscow or Washington, D.C. In history books, it is treated as a footnote to the 1914-1918 war. And when you ask the ordinary person in the street—any street in the world—to name the worst disasters of the 20th century, they rarely mention it. Why?

The answer is not straightforward. Historian Alfred Crosby’s important account of the United States’ experience of the pandemic, America’s Forgotten Pandemic (1976), could not be published under that title today, because we are more aware of it than we were 40 years ago. Even in 1976, the same people who excluded the Spanish flu from their list of the major disasters of the 20th century—and let’s face it, it was a particularly disaster-prone century—often had a family memory of the pandemic, and the same is true today. They can name a great-uncle who died of it, distant cousins who were orphaned, a branch of the family that was simply rubbed out in 1918. The Spanish flu is remembered, not as a historical disaster, but as millions of discrete, private tragedies. And for that reason it offers us a fascinating insight into the nature—and fallibility—of collective memory.

Influenza is caused by a virus, but virus was a novel concept in 1918, and there was no diagnostic test for flu. That means that there was no such thing as a laboratory confirmed death from the disease, a fact that goes a long way to explaining that vast range in the estimated death toll. There is still a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the number of victims. Until the 1990s, people thought that around 22 million people had died. It wasn’t until 1998, the 80th anniversary of the disaster, that Australian historian and geographer Niall Johnson and German flu historian Jürgen Müller came up with the current estimates, which means that for 80 years humanity only had a tiny inkling of its loss in 1918. It was really only in the 21st century that people realized the full impact of the Spanish flu.

Scholars in the humanities, who have long been interested in collective memory, point out that impact is not the same as meaning. Meaning depends on language—that is, on having the language available to describe exactly what happened and why. That language was lacking in 1918. In large swathes of the world, people still viewed epidemics as acts of god and considered themselves helpless against them. Divine retribution, or vindictive spirits, was often the only explanation they could offer for what they saw as a cruel and random lottery—the fact that not everybody was equal before the disease. Men were more vulnerable than women, for example, and some age groups were at greater risk than others—notably the very young, the elderly, and an intermediate age group of 20-to-40-year-olds. But the plague’s lethality didn’t only vary across time, it varied across space too. If you lived in certain parts of Asia, you were 30 times more likely to die of the Spanish flu than if you lived in certain parts of Europe. New York City lost 0.5% of its population, Western Samoa 22%.

We now have the vocabulary to explain these troubling disparities. Concepts like immune memory and genetic predisposition have taken over that task from divine retribution. We understand that social and economic factors shape health as much as biological ones—something that was much less well appreciated at the time. And we have it in our linguistic toolbox to explain other features of the pandemic too, that were inexplicable then—features such as the subsequent wave of lethargy and “melancholia” (depression) that washed over the world. Today, we call this postviral syndrome. We know that the flu virus can affect the central nervous system, producing neurological and psychiatric symptoms. As these concepts were recognized and labelled, the pandemic began to acquire meaning—or rather, a different meaning: the one we recognize today. But it took time.

The hypothesis that I lay out in my book, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, is that wars and pandemics are remembered differently. Collective memories for war seem to be born instantly, fully formed—though subject, of course, to endless embellishment and massage—and to fade over time. That’s because we’ve never not had the vocabulary of war: the enemy is familiar, after all. The casualties of war are easier to count, too, or at least they were up until 1918. They tended to wear uniforms, display exit wounds and fall down in a circumscribed arena. Not so the victims of infectious disease. Memories of cataclysmic pestilence therefore build up more slowly, and once they have stabilized at some kind of equilibrium—determined, perhaps, by the scale of death involved—they are, in general, more resistant to erosion.

We’re at an interesting point on the remembering/forgetting arc with respect to the 20th century. The two world wars are still raw, we revisit them obsessively and are firmly convinced we will never forget them—though experience suggests that they will gradually fade in our memories, or be eclipsed by other wars. Meanwhile the Spanish flu intrudes more and more into our historical consciousness, but it can’t shake the prefix “forgotten.”

By the time the bicentenary swings round, I think it will have finally broken free from that prefix. There is a precedent in the 14th century Black Death, after all. Like the Spanish flu, it overlapped with a war—the Hundred Years’ War, in its case. Like the Spanish flu it was far more lethal than the war with which it overlapped. But unlike the Spanish flu it is not treated as a mere footnote to that war. That the Black Death gets its own psychological “monument” is a tribute to the generations of researchers who have calculated its impact and imbued it with meaning. The Spanish flu only happened 100 years ago. Its monument is a work-in-progress.

Laura Spinney is a science journalist and a literary novelist. She has published two novels in English, and her writing on science has appeared in National Geographic, Nature, The Economist, and The Telegraph, among others. Her latest book is Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World (PublicAffairs, 2017).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com