Christian R. Greco found the earliest known photographs of his family by accident. In the wake of President Trump’s decision to walk back some protections for young undocumented immigrants, the historian and legal activist couldn’t help but think about his own family’s immigration experience and his father’s journey to New York from Italy in October of 1950. Inspired to look for images from Ellis Island from that period, he stumbled upon a LIFE.com gallery that contained several Alfred Eisenstaedt photos that were never published in the magazine.

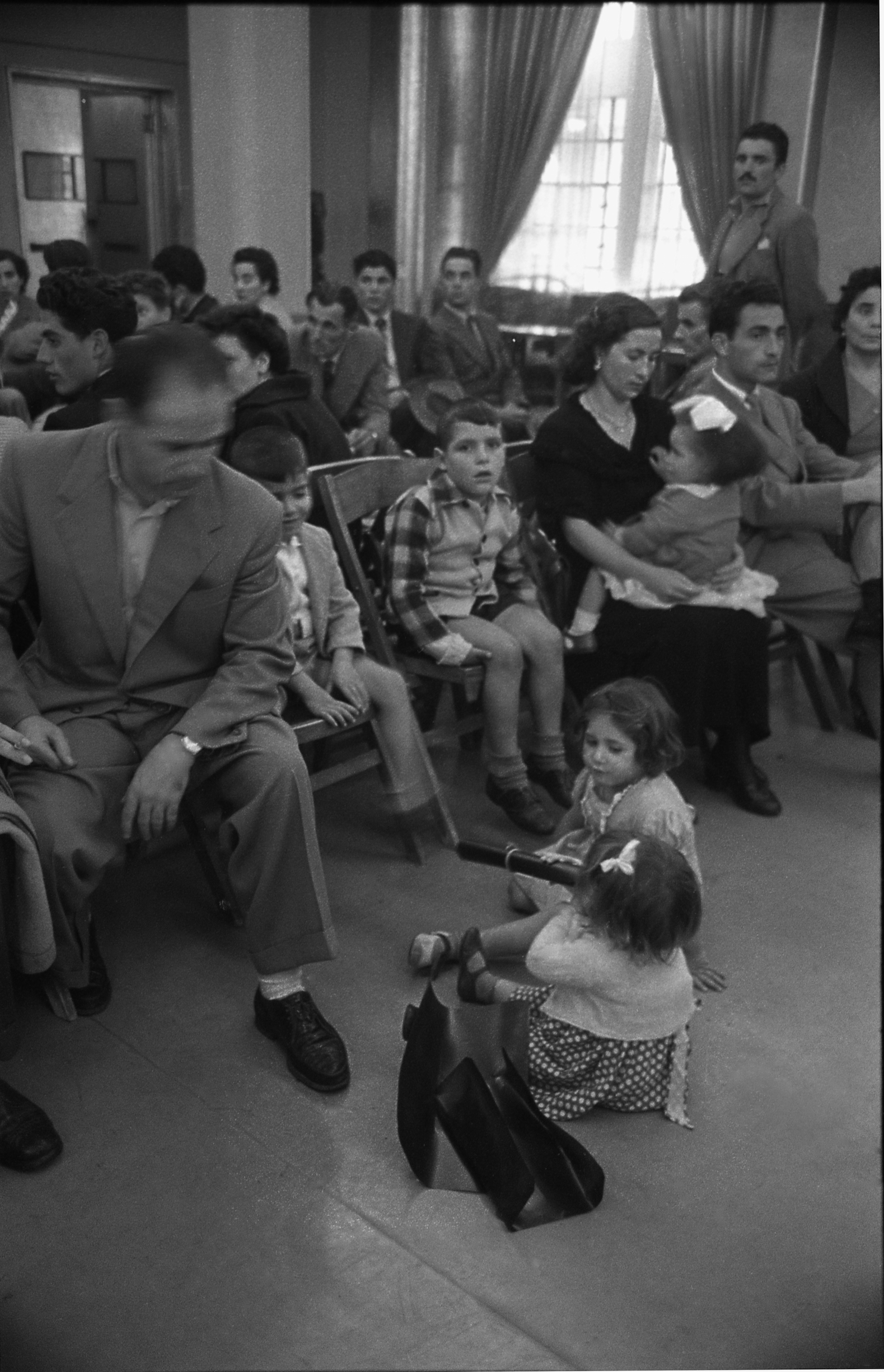

One of them, of a man waiting with his children, caught Greco’s eye. And that man, he was fairly sure, appeared to be his own grandfather, Raffaele Greco.

Greco’s stunned father, seen in the photo as the little boy seated at right in the image, confirmed the match. Because the image had not been published in the magazine, the family had not known about its existence until that moment. And when the photo inspired Greco to do more digging into his family’s past, he found new layers of a story that his grandfather had kept to himself for his entire life.

The family’s immigration story, as reconstructed by Greco, who now lives in the Washington, D.C., area, begins in the town of Rende in Italy’s Calabria region. In the years after World War II, the family was well-off for the time and place, but not by American standards. Christian Greco’s grandmother Rose was American but she met his grandfather in Rende and settled there as their family grew. The couple decided that they ought to make the move to her homeland around 1950, though the precise reasons for that timing have been lost to family memory.

Some months after Greco’s grandmother and her eldest son made their way to the United States, her husband and their four younger children followed on a liner called the Saturnia, arriving on Oct. 22, 1950, after an 11-day journey in what was essentially steerage from Naples to New York City’s Pier 84. Christian Greco’s father Michael, at 7, was the oldest of those four. (The other three children in the photo are Allen, Vivian and Anna Marie, ages 5, 3 and nearly 2.)

Unbeknownst to them, they had not picked a good moment to come to America.

Just weeks earlier, the U.S. Congress had passed a law called the Internal Security Act of 1950, also known as the McCarran Act. In an environment of tense McCarthy-era Cold War fear, the act was billed as a way to keep the nation safe from the insidious influence of communism. The way it was framed, however, was a problem — so much so that the law passed despite a veto by President Truman, who argued that the act would help communists by proving that the United States was not the free nation it claimed to be.

As TIME explained in the wake of the episode, the way the law was written had made such an outcome fairly inevitable:

The letter of the law did not give much choice. It banned any alien who “at any time” had been “affiliated” with any “section, branch, affiliate, or subdivision” of any “totalitarian party.” Under Hitler, nearly every youth was forced to join one or another of the Hitler Youth organizations; nearly every man who worked for a living had to belong to a Nazi-dominated labor union. In Italy, every school was a Fascist school. Officials estimated that the new law would exclude 90% of all Germans, more than half of all Italians. It would bar all repentant Communists, interfere with trade with Yugoslavia, exclude many of the 55,000 German refugees from East Europe, whose admission Congress had just authorized last June.

As one 1950 New York Times Magazine article noted, immigrants who thought that their visas were already settled were “baffled and bitterly disappointed” to arrive in New York City only to be detained under the act. To deal with the bottleneck before it became a crisis, the State Department soon cancelled all U.S. visas for those who had not yet arrived, but it was clear the law would need fixing. (Though its constitutionality was at first upheld when challenged and select portions of the law still stand, many parts of it were struck down over the next few decades. Meanwhile, on Nov. 12, 1954, Ellis Island closed as an immigration center.)

In the meantime, as the Saturnia pulled into the pier in October of 1950 and law-enforcement officers began to approach the ship, the passengers — including the Grecos — didn’t know what to expect.

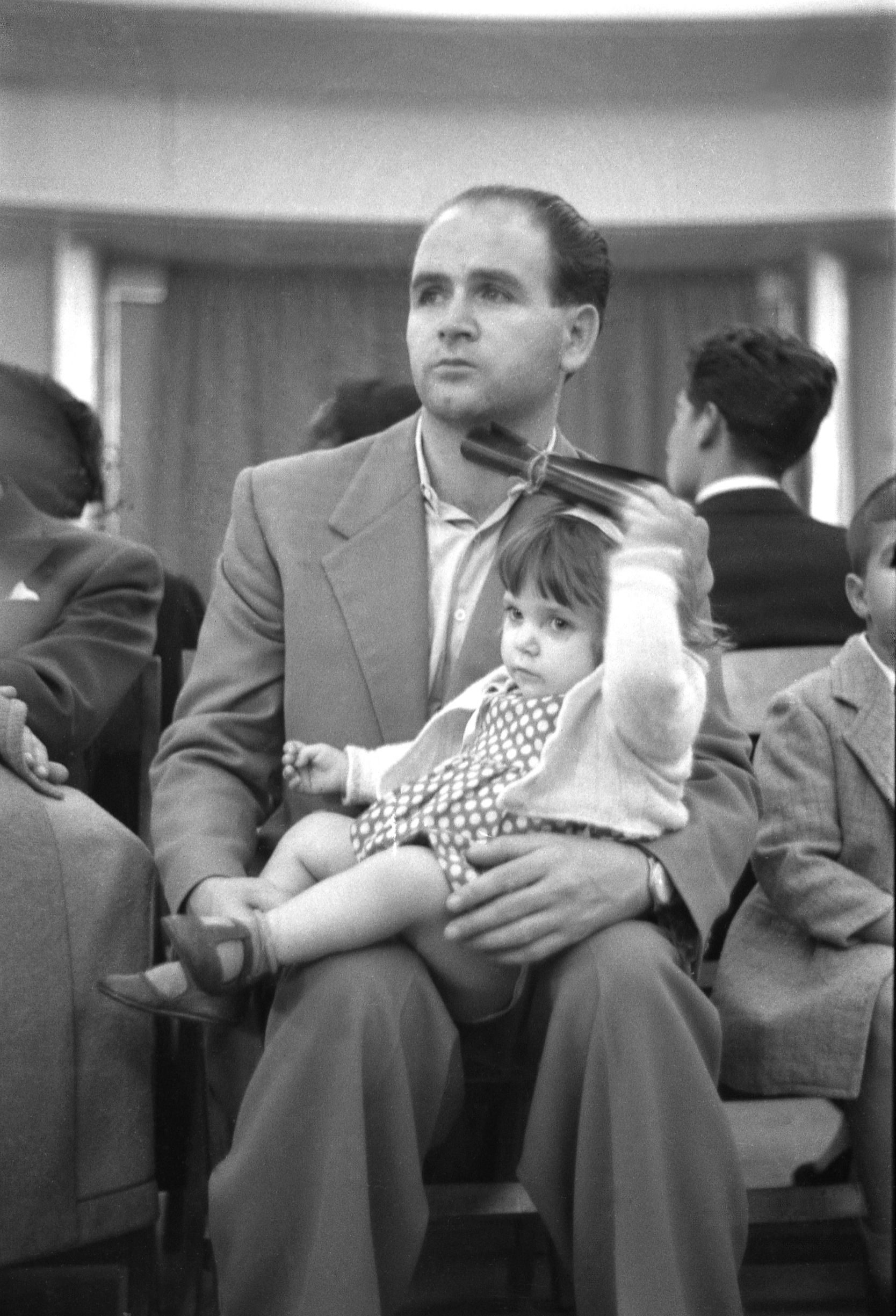

It was the McCarran Act that brought LIFE’s Alfred Eisenstaedt out for a story that was published in the Nov. 13, 1950, issue of the magazine, which dubbed Ellis Island “a gray and gloomy place suddenly full of bewildered people who have become victims of American politics.” The photographer met the hundreds of detained immigrants aboard the Saturnia, where they were crammed into a luxury lounge to await interrogation and then, for many, transfer to Ellis Island for further questioning and detention. According to news reports from the time, the 130 Saturnia passengers who were detained comprised the largest group held under the law at that point. Though only a few of the images would be published in LIFE, Eisenstaedt shot pictures throughout the ordeal and they are still part of the LIFE Picture Collection.

“It’s fascinating to look at the faces of some of these people, including my grandfather,” Greco says. “You can just see the ebb and flow of emotion as people are at first surprised, confused, and then they start to get worried and some of them are in tears as the day goes on.”

Greco says that his grandfather had been conscripted into an Italian fascist youth corps in the 1920s and then into the Italian army during the war, and that was enough of a red flag to trigger the McCarran Act — even though the same would have been true for pretty much any Italian man of that age.

It would take days — accounts differ on exactly how many — for the Grecos to be released into the United States to reunite with their family. But, with the children young and the family ultimately proving to be the kind of immigrant success story that America loves (Greco’s father was the first immigrant to be president of the American Bar Association, for example), those terrifying first few days were rarely discussed. Each of the Greco children, of whom there would be a total of ten over the course of Raffaele and Rose’s half-century-long marriage, developed a slightly different version of the story, but the law didn’t figure heavily in any of the versions that made their way to the next generation. “It was news to us a month ago when I started to discover these photographs that we were even victimized by this act,” Greco says.

To Greco, the information he has gathered about the law and his own family’s story has only added another layer to the apt timing of his initial discovery. After all, if it hadn’t been for today’s debate over immigration, he might never have found the photograph — or have learned that the debate had a precursor through which his own family lived.

“I’m a first-generation Italian immigrant,” Greco says, “and as the child of someone who has now learned this story and learned that we were victimized by a law similar to what Trump is trying to do by detaining certain people based on their point of origin, it struck a chord with me that I wasn’t aware was a chord until I read about it.”

Though there are still gaps in what the Greco family knows about that period, the discovery of Eisenstaedt’s photographs of that day have been a start toward a complete story — one that only makes him appreciate more than ever the bravery of his grandfather, crossing an ocean with little money but four small children, to a land where he didn’t speak the language but where dreams for his family’s success would eventually come true. Looking at his grandfather’s face even on that stressful day so many decades ago, he sees a spark of the confidence that would carry Raffaele Greco forward, like so many other immigrants before and after.

“Without Eisenstaedt and LIFE we wouldn’t have known this,” he says. “I don’t think it ever would have been realized by the family.”

Correction: The original version of a photo caption in this gallery misidentified the vessel the passengers were on immediately prior to processing at Ellis Island. It was a ferry, not the Saturnia.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com