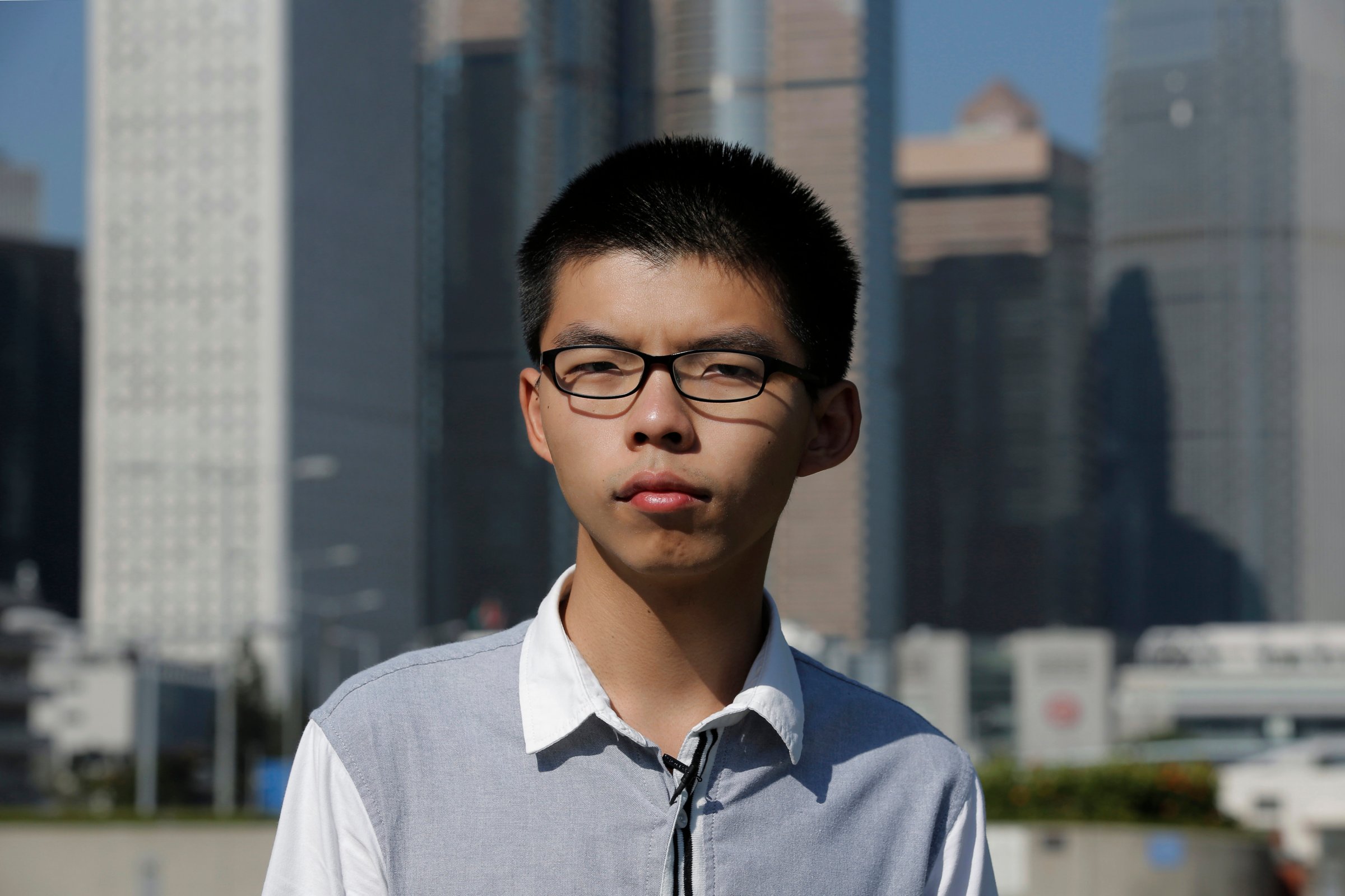

A little more than three years ago, Joshua Wong marked his 18th birthday amid tens of thousands of people occupying a stretch of Hong Kong’s financial district. The protests, for greater democracy, lasted nearly three months and made student activist Wong a global icon — a Netflix documentary about him has been submitted for the Oscars.

On Oct. 13 this year, Wong marked another important birthday: He turned 21, not among friends and supporters, but in a prison cell. Wong was convicted in August for his role in what came to be called the Umbrella Movement — the charge was inciting others to take part in an unlawful assembly — and sentenced to six months’ jail. He was also separately convicted of other charges related to the 2014 demonstrations. Wong has been granted bail pending appeal, but there’s still the potential for extra prison time over the second case.

Since the Umbrella Movement ended, the outlook for Hong Kong’s democratic progress has been bleak. Besides Wong, many other activists have been jailed. Some were elected in 2016 to the local legislature, but earlier this year Beijing made a legal ruling that ousted six of those young, liberal lawmakers on technicalities.

Hong Kong has a new leader (known as the Chief Executive), Carrie Lam, selected by a pro-Beijing electoral college. While Lam, a career bureaucrat, is not as hardline in word and deed as her predecessor Leung Chun-ying, she is an establishment figure and toes Beijing’s line on politics.

Read more: Joshua Wong, the Voice of a Generation

In the face of these developments, the 2014 protesters’ original goals — free elections for the Chief Executive and the entire legislature — remain unlikely. Many Hong Kong citizens say that “One Country, Two Systems,” the template that promised the territory considerable autonomy after its return to China from Britain in 1997, is under strain.

TIME sat down recently with Wong to talk about life behind bars, the future of Hong Kong and the way forward for his cause. The interview has been translated from Cantonese, and edited for length and clarity:

How has it been inside?

I’m still in the process of adjusting. But it wasn’t as over-the-top as I’d imagined. There were fights, but I didn’t witness any; also, I wasn’t beaten. It wasn’t like in Prison Break. The way I see this reported in international media, some people outside Hong Kong must’ve thought that I was in a Prison Break kind of prison. I mean, come on…

But life in prison comes with limitations on you, not just physically.

Apart from the dietary stuff, there’s also disciplinary training in the form of foot drills. Their logic is that if you learn to obey orders inside, you will learn to abide by the law outside. But I don’t think doing foot drills well inside translates to following the law outside. I don’t think there’s a linear relationship there for, say, youngsters engaged in drug-trafficking. Another thing is that you cannot say no. Normally you reply “Yes, sir” during foot drills. But then, for example, I might say “no” when you ask me if there is anything I wish to add — in prison, the way to give a “no” answer is to say: “Sorry, sir.” In other words, “sorry” becomes the substitute for “no.” Why is it that I have to apologize in order to express an answer in the negative? Do I owe you something? That’s their logic. One other thing is that you can’t put your cup on the desk if you meet with correctional officers; you must put it on the floor. It doesn’t take up much space on the desk — why can’t inmates put their cups there? This is their way of showing hierarchy. [Ed. note: Hong Kong’s Correctional Services Department tells TIME via email that this is not official policy.]

How did you keep abreast of what’s happening outside while behind bars?

Each inmate can only subscribe to one newspaper inside, and I chose [the liberal] Apple Daily. We also get news on TV during mealtime, but it could be during meals or after meals. Why bother if you only put on the news channel for 10 minutes after meals? That really depends on specific officers. In addition there are letters, which help a lot. Many supporters sent letters to me. Between August and September, I received a total of 777 pages of letters. Normally you don’t count the pages of letters, but I did because I had to let my family help me take them out. It would be troublesome for me to carry a thick stack of letters out of prison. Everything that gets taken out of a high-security prison has to be checked, so turns out there were 777 pages of mail in total… These letters help me feel less distant from the outside.

You said that you have learned to adjust your pace. Does that have to do with your experience inside?

Your pace becomes slower. I think less fast, too, because there’s no need to think inside prison. From 6:30 a.m. to 10:30 p.m., everything you do is scheduled. You don’t get to make decisions. There are no options at all. It makes the inmates feel constrained, for sure, but I think that even applies to the staffers. To do the same things day after day in the same enclosed environment with no variation — think about it: after training, they spend 30-odd years in prison, looking after the dozens of inmates they are responsible for, with little else to do. You would go mad if you worked there.

Did you ever think you would eventually land in prison?

By the time Umbrella rolled around, the possibility of going to jail crossed my mind. As for whether I was mentally prepared for prison, Hong Kong has entered an authoritarian era, but it’s a paradoxical one, a modern one. First is a psychological thing, that for hardcore Hong Kong activists to go to prison, 90 days may be bearable, but maybe not 900 days. Second is the notion that, as of now, prison sentences for those fighting for democracy in Hong Kong are relatively short compared to the long sentences faced by people like Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi or activists in Taiwan — it’s nothing in comparison. But the other way to look at this is that getting imprisoned in this age of free-flowing information will create a severe disconnect. It might well be that the information gap created by a year’s imprisonment 20 years ago is the same as what you’d miss out today by being jailed just for a month.

What does the spate of prosecutions and jailings of Hong Kong activists say about the state of Hong Kong and China relations?

It’s simple when it comes to Hong Kong: Even a movement fighting for free elections, which basically the entire world considers peaceful, can result in imprisonment. What we want, essentially, is to elect our mayor ourselves. But [Chinese President Xi Jinping’s] emphasis on “comprehensive jurisdiction” over Hong Kong has overridden the “high degree of autonomy.” Hong Kong being the place in China where there is still free information, where there are still young people who put up a fight, go to jail, then continue to fight even after getting out of jail — I’m talking about me — our passion is worthy of being witnessed by everyone. Plus, people like to talk about a right-wing wave in the past five to 10 years — despite this wave and the uncertain international climate, the fact that a group of people are still fighting for the most basic values should be appreciated.

What does the situation in Hong Kong tell the world about China?

If you talk about getting imprisoned for political reasons, then Hong Kong is nothing compared to China, where conditions can be much worse. But if democracy and authoritarianism are two ends of a scale, we used to describe Hong Kong as semi-democratic. Now, people think it’s veering toward more control; that’s why we say semi-authoritarian now.

Benedict Rogers, the British human-rights campaigner who has spoken up on your behalf, was barred from entering Hong Kong ahead of your birthday. What do you make of it?

Ben Rogers being barred from entry is very serious. I learned about Rogers’ denial of entry in prison from the news on TV. This was totally unexpected, as I knew even before my imprisonment that he was going to come. In the past, it was the likes of Taiwan independence advocates or Chinese dissidents in exile who couldn’t enter Hong Kong, but those are causes that the Chinese government refuses to acknowledge. Now it’s the vice-chair of the U.K. Conservative Party’s human-rights commission. Isn’t that over the line? My first reaction when I saw the news was, you might as well bar [former British governor] Chris Patten from the city next time around. Then Carrie Lam said on the next day that the possibility couldn’t be excluded. I was stunned. U.S. or U.K. lawmakers do occasionally visit Hong Kong. For example, a group of U.S. congresspeople came a week after Rogers was turned away, while a U.K. Foreign Office secretary in charge of Asia affairs came in August. It’s normal in and of itself for politically-connected people to come to Hong Kong, whether for sightseeing, for visiting friends or for business exchange. Heck, even [pro-Beijing lawmakers] Holden Chow and Starry Lee met the U.S. lawmakers. What the Ben Rogers incident reflects is that, in terms of its impact to U.K. politicians, they might well never be able to set foot in Hong Kong. Such a scenario could happen. When Carrie Lam can say that Chris Patten might be barred from entry, the situation has elevated to such a level in international relations that if you’re not friendly to China you couldn’t enter Hong Kong. How do we face the possibility that they couldn’t enter such a global city as Hong Kong?

Read more: Xi Jinping Becomes China’s Most Powerful Leader Since Mao Zedong

Chris Patten isn’t a threat to the Chinese state. Ben Rogers didn’t have any public events planned — his visit would’ve involved private meals with pro-democracy figures for the most part. So overall, the latest Chinese policy has become that, like Tibetan independence advocates, British people who care about Hong Kong can’t enter. How are these two on the same level? Going further still, does it stop at politicians?

Even more activists are facing imprisonment over Umbrella and other protests. What message do you have for them?

I do hope that the international community pays attention to those other than me. Right now in Hong Kong, more than 20 political prisoners remain behind bars. And I have to emphasize this: I’m not free, I’m simply on bail. So now over 20 are inside, and nearly 100 others are waiting for their trials. Their jail terms will be longer than mine. My six-month sentence is the shortest among all current political prisoners in Hong Kong.

You’ve called Hong Kong’s path to democracy “exhausting.” Realistically, how do you persuade the people of Hong Kong to remain hopeful?

One reason is that Hong Kong’s fight for democracy has received such widespread international support and attention. So why do we need to give up? In prison I would remind myself that, though I might not be able to change the environment, I can change myself and cope with the environment while keeping my mind free. In the same vein, though we can’t change this semi-autocratic environment of ours, we can all adjust our mindsets to cope with it, without getting used to it. Hong Kong can’t yet be described as a prison, but it’s still an imprisoned place. Why do I see hope? Everybody’s on our side.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com