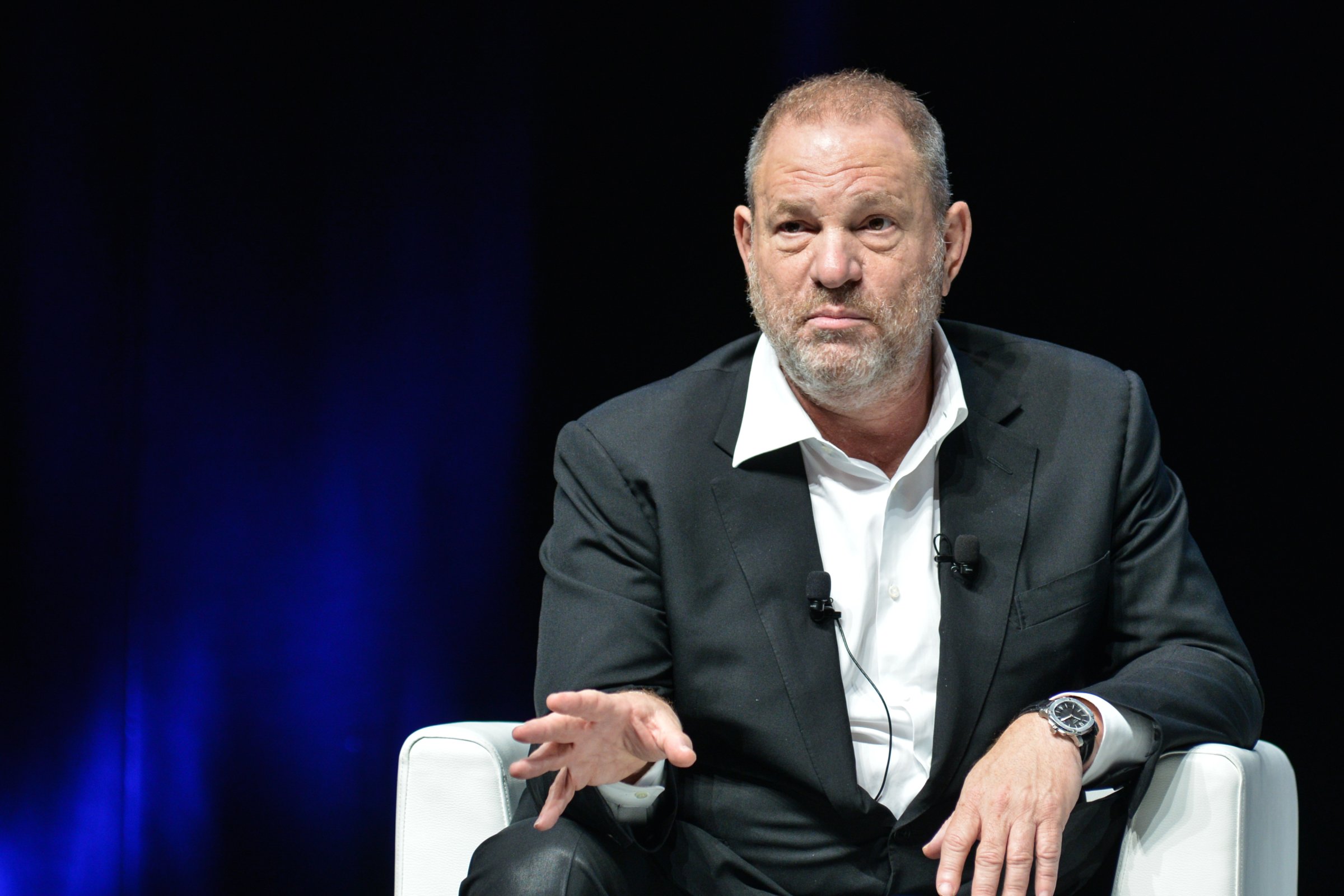

The Weinstein Company Board of Representatives has claimed it was “shocked and dismayed” to learn from news reports that Harvey Weinstein, one of its owners and co-founders, had sexually harassed employees and actresses for decades. In response, it summarily fired him, announced it was seeking to change its name, and even began striking Mr. Weinstein’s name off of its television credits.

While this response is justified, the fact that it comes only now, suggests the company was more outraged by the exposure of the conduct than the conduct itself.

Mr. Weinstein reportedly made payments to at least eight women while he was at Miramax and the Weinstein Company, and lawyers and executives at the latter were aware of some of those payouts for at least the last two years. Where was the outrage then? The conduct was the same. The impact the conduct had on the accusers was the same. All that changed was the publicity.

The real story here is not what the Weinstein Company is doing now, but what it — and others in corporate America — have not been doing. Rather than investigate the complaints of sexual harassment by a powerful company executive and demand that it cease, companies have swept illegal conduct under the rug and allowed it to continue. Quite simply, the serious impact that the behavior caused to the alleged victims took a back seat to the importance of the accused harasser’s power and value to the company.

The Weinstein Company is far from the only offender. Fox News only parted ways with Roger Ailes and Bill O’Reilly once public exposure of allegations that had swirled or been known for decades created a public relations nightmare for the network. And the list goes on and on, and includes prominent entertainment figures, athletes, politicians, two presidents and a Supreme Court justice. So long as our society continues to allow the dismissal of sexual harassment as “locker room talk” or resents women for spoiling a “boys will be boys” culture, no workplace will be immune from this problem. Since sexual harassment at its core is really about power, any employee – from the lowest paid to the highest – may fall victim when a boss or co-worker uses their advantage of power over someone else’s livelihood or career.

Workplace sexual harassment is illegal, and the law provides protection to employees who report it. If the employer finds that the employee’s complaint has merit, it must take appropriate steps to end the harassment without adversely affecting the work or position of the employee. But the law can only succeed if victims aren’t afraid – despite the stated protections – to use it. And the practical reality is that few are, and those who do are frequently branded and humiliated by the alleged harasser or his supporters as liars, jilted, revengeful or worse.

In representing victims of discrimination and harassment for many years, all too often the company’s response follows one of two routes: denial that the conduct occurred, or a conclusion after an “investigation,” to which only the company is privy, that the victim’s allegations could not be substantiated. It’s also not unusual to find that co-workers who witnessed the harassment are afraid to corroborate claims out of fear for their own jobs, particularly if the accused wields power over them as well. Other co-workers may turn on the accuser, upset that they’re overreacting, threatening the position of a friend or stifling the work environment.

Sometimes, a company may respond even more aggressively and the complaining employee may find themselves accused of inappropriate behavior. And even if the company concludes that a monetary settlement is desirable, it will likely be conditioned on: no admission of liability, strict confidentiality and often an agreement that the employee leave the company and find new employment.

Thus, despite legal protections, employees’ fears that any accusation is more likely to further victimize them, their livelihood and career are real. Many are simply not willing to take that personal risk.

This practical reality allows sexual harassment to proliferate and prevents the anti-discrimination laws from achieving their goal of ridding the workplace of harassment, and protecting employees against retaliation for reporting it.

But this goal could be readily achieved if companies start demonstrating genuine outrage over exploitative and degrading behavior that has no place in the workplace, no matter who the harasser is. They must afford victims the dignity of taking their claims seriously. They must confront the harasser and take whatever steps necessary to protect their employees from the offensive behavior. By such actions, employees will learn that they need not fear speaking up, and this type of behavior will become much less prevalent.

Geri Krauss is a lawyer in New York City who has handled numerous claims of sexual harassment, the most well known being her representation of an employee who asserted claims of sexual orientation discrimination and harassment against Leona Helmsley, which resulted in an $11 million verdict.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com