Deep inside the Googleplex, a small group of writers is huddling around a whiteboard that is plastered with ideas. These read like notes-to-self that Jack Skellington might’ve made: “Halloween survival kit,” “How to defeat monsters.” One in particular stands out to Ryan Germick, a tall and wiry 37-year-old. “People did not like ‘smell my feet’ last year,” he says, laughing. His colleague Emma Coats chimes in to explain:

“It was trick or treat, and one response was ‘smell my feet.’ People thumbed-down the heck out of that.”

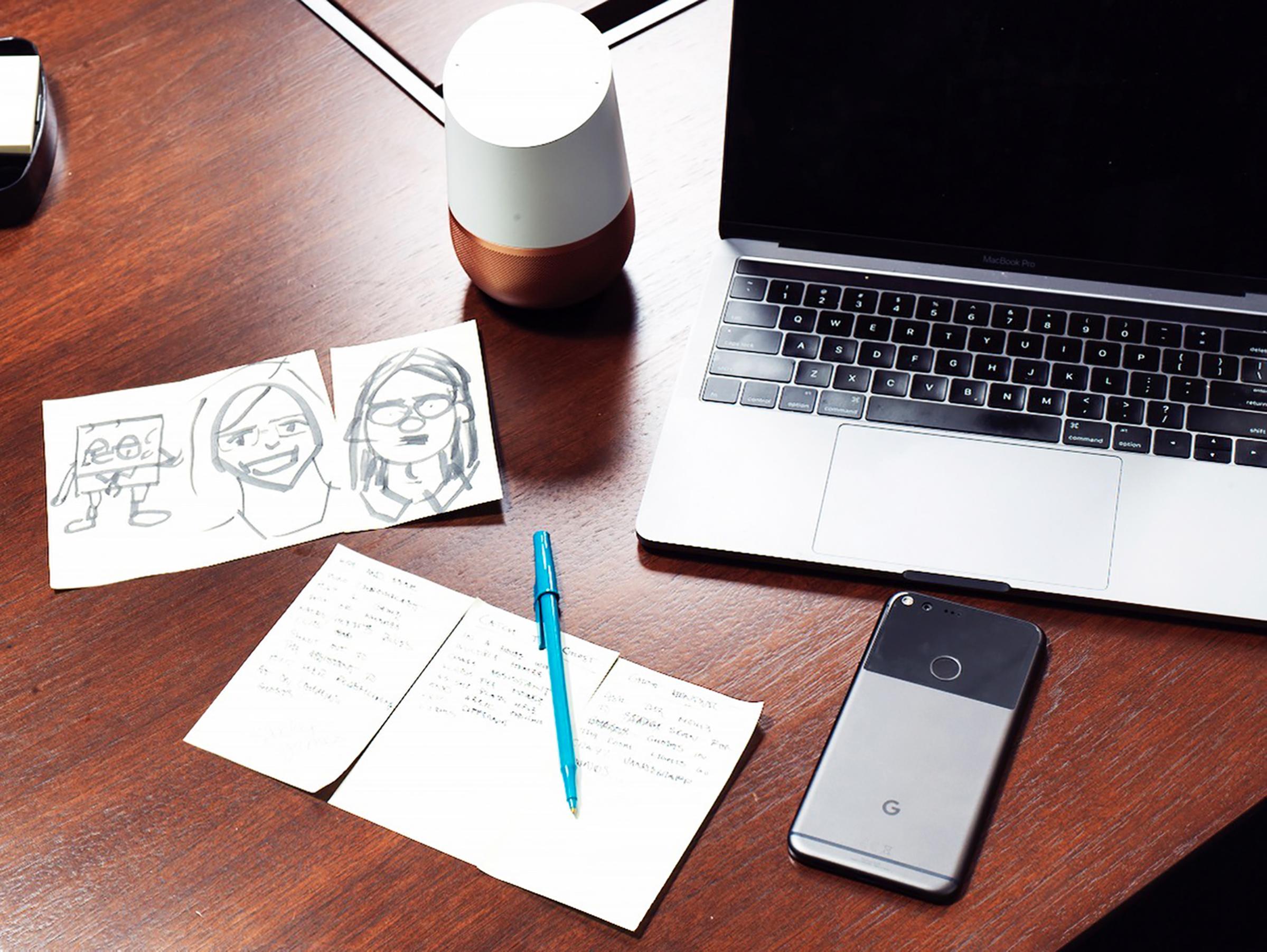

Germick has spent the afternoon bouncing between brainstorming meetings like this one, in which Googlers debate life’s big questions, like whether the sound of a bubbling cauldron or distant howling is spookier. All of which is part of his job as principal personality designer for Google Assistant, the company’s voice-activated helper found on a wide range of smartphones and its Home smart speaker, which first went on sale last fall.

It’s August, but Germick’s team is grappling with what users might ask Google on Halloween and why. Will people turn to Assistant for costume ideas? Or will they want to hear a seasonally appropriate joke? The key to answering these kinds of questions, Assistant’s creators maintain, is not to think of Google as most of us have come to–a dispassionate dispenser of information–but as a dynamic character. “At the very simplest level,” says Lilian Rincon, director of product management for Assistant, “it’s, Can I just talk to Google like I’m talking to you right now?”

This is harder than it sounds. And over the past few years, developing voice-enabled gadgets has become one of Silicon Valley’s most hotly contested technology races. Assistant is available on phones from the likes of Samsung and LG that run the Android operating system. Amazon offers its take, Alexa, on its popular Echo speakers. Apple has built Siri into a plethora of iDevices. And Microsoft is putting its Cortana helper in everything from laptops to thermostats.

With so many companies rushing to make such a wide variety of devices capable of listening and talking to us, it’s hard to quantify how quickly the technology will become mainstream. But this year, 60.5 million Americans will use Alexa, Assistant or another virtual butler at least once a month, according to research firm eMarketer. Sales of smart speakers alone will reach $3.52 billion globally by 2021, up nearly 400% from 2016, predict analysts at Gartner. Many technology experts are convinced that voice is the next major shift in how humans use machines. This will be “a completely different level of interaction,” says Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, a research outfit in Seattle. “This really becomes a game changer when you can have a dialogue with a virtual assistant that may be at the level of a concierge at a hotel.”

But barking orders at a computer is not the same thing as having a conversation–which puts Google in an unusual position. The firm became one of the most valuable companies in the world by building technology capable of doing what no human conceivably could: indexing vast troves of online information. Now it’s future may hinge on teaching machines to perform a task that comes naturally to most people, but has proved to be profoundly difficult for computers: small talk. To do so, the company has turned to a team of left-brained creative types that Google isn’t exactly known for hiring: fiction writers, filmmakers, video-game designers, empathy experts and comedians. If they succeed, they’ll give Google something it’s never had before: a personality.

Digital assistants are nothing new. In 1952, Bell Labs’ Audrey computer was capable of recognizing spoken numeric digits, but it consumed huge amounts of power and couldn’t understand voices it wasn’t trained to. In 1990, Dragon Systems unveiled Dictate, software that had a vocabulary of 30,000 terms but required the speaker to pause awkwardly between each word. And in 1997 the field got its poster child for what can go wrong. That year Microsoft introduced Clippy, a cartoon paper clip intended to anticipate Office users’ needs and answer questions. But in practice, Clippy was a worse bumbler than C-3PO, popping up inconveniently more than it ever helped. (It didn’t talk, thank God.) The feature became a punch line and was retired ignominiously in 2007.

It wasn’t until six years ago that the noble idea behind Clippy–predicting what information you might need next, offering the right tips at the right moment, this time packaged in a friendly voice–came to fruition in Apple’s Siri. She could understand questions in context and apply a level of intelligence before answering out loud. Plus, she was funny. Before long, every one of Apple’s competitors was working on similar technology.

This hit-or-miss history isn’t lost on the Googlers now working on Assistant. Germick, who has dressed up as Clippy for Halloween, argues that future assistants have to be more than just question-and-answer machines. After all, Google search already does that pretty well. “We want you to be able to connect with this character,” he says. “Part of that is acknowledging the human experience and human needs. Not just information, but also how we relate to people.”

Making that character seem plausible falls to Google’s personality team, which has been working on turning Assistant into a digital helper that seems human without pretending to be one. (That’s part of the reason, by the way, that Google’s version doesn’t have a human-ish name like Siri or Alexa.) Coats, whose title is character lead for personality, draws on years of experience developing fictional characters. She spent five years at Pixar Animation Studios working on films such as Monsters University, Brave and Inside Out. “It takes a lot of thinking about what are the other tools besides facial expressions that can be used to make emotional connections,” she says.

Coats tells me about the questions Googlers consider when crafting a response that’s lively but not misleading. Among them: What does the user hope to get out of the interaction? How can Google put a positive spin on the answer? How can it keep the conversation going? Then Coats gives me a specific example: When asking Assistant if it’s afraid of the dark, it won’t respond with an answer that suggests it feels fear. Instead it says, “I like the dark because that’s when stars come out. Without the stars we wouldn’t be able to learn about planets and constellations.” Explains Coats: “This is a service from Google. We want to be as conversational as possible without pretending to be anything we’re not.”

This often involves analyzing the subtext of why someone may have asked a particular question in the first place. When asked “Will you marry me?”–a request Google says it’s seen tens of thousands of times–Assistant doesn’t give a straight answer, but deflects that it’s flattered its owner is looking for more commitment.

Questions like this can be banal or emanate from complex emotions. While it’s unlikely anyone presenting Assistant with a marriage proposal expects a serious answer, the company is trying to systematically understand how various emotional states differ from one another. Danielle Krettek’s job at Google as an empathic designer is to help the creative writers do that. It’s easiest to think of Krettek’s role as a sort of emotional interpreter. Not long after sitting down with her, I understand why: she’s bubbly and animated, with facial expressions that telegraph exactly how she’s feeling at any given moment. “There are things that people feel and say, and there are the things they don’t say,” she tells me. “My ability to read that is what I bring to the team.”

Krettek talks her colleagues through the ways in which people experience emotions differently, particularly feelings that are similar and may be easily confused. She might delve into how disappointment is distinct from being angry. Or, say, why feeling mellow isn’t the same as satiation. This is supposed to help the writers come up with responses that provide a sense of empathy. Take Assistant’s answer to the phrase I’m stressed out. It replies, “You must have a ton on your mind. How can I help?” Says Krettek: “That acknowledgment makes people feel seen and heard. It’s the equivalent of eye contact.”

Google’s personality architects sometimes draw inspiration from unexpected places. Improv, both Coats and Germick tell me, has been one of the most important ones. That’s because the dialogue in improv comedy is meant to facilitate conversation by building on previous lines in a way that encourages participants to keep engaging with one another–a principle known as “yes and.” Germick says almost everyone working on personality at Google has done improv at some point.

You’ll get an example of the “yes and” principle at work if you ask Assistant about its favorite flavor of ice cream. “We wouldn’t say, ‘I do not eat ice cream, I do not have a body,'” explains Germick. “We also wouldn’t say, ‘I love chocolate ice cream and I eat it every Tuesday with my sister,’ because that also is not true.” In these situations, the writers look for general answers that invite the user to continue talking. Google responds to the ice cream question, for instance, by saying something like, “You can’t go wrong with Neapolitan, there’s something for everyone.”

But taking the conversation further is still considerably difficult for Assistant. Ask it about a specific flavor within Neapolitan, like vanilla or strawberry, and it gets stumped. Google’s digital helper also struggles with some of the basic fundamentals of conversation, such an interpreting certain requests that are phrased differently from the questions it’s programmed to understand. And the tools Google can use to understand what a user wants or how he or she may feel are limited. It can’t tell, for instance, whether a person is annoyed, excited or tired depending on the tone of their voice. And it certainly can’t notice when facial expressions change.

The best characteristics Google currently has to work with are a user’s history. By looking at what a person has previously asked and the features he or she uses most, it can try to avoid sounding repetitive. In the future, Google hopes to make broader observations about a user’s preferences based on how they interact with Assistant. “We’re not totally there yet,” says Germick. “But we’d be able to start to understand, is this a user that likes to joke around more, or is this a user that’s more about business? The holy grail to me is that we can really understand human language to a point where almost anything I can say will be understood,” he says. “Even if there’s an emotional subtext or some sort of idiom.”

When that will be exactly is unclear. Ask most people working on voice in Silicon Valley, including those at Google, and they will respond with some version of the same pat phrase: “It’s early days,” which roughly translates to “Nobody really knows.”

In the meantime, Google is focusing on the nuances of speech. When Assistant tells you about the weather, it may emphasize words like mostly. Or perhaps you’ve noticed the way its voice sounds slightly higher when it says “no” at the start of a sentence. Those seemingly minor inflections are intentional, and they’re probably James Giangola’s doing. As Google’s conversation and persona design lead, he’s an expert in linguistics and prosody, a field that examines the patterns of stress and intonation in language.

Of all the people I meet on Google’s personality team, Giangola is the most engineer-like. He comes to our meeting prepared with notes and talking points that he half-reads to me from behind his laptop. He’s all business but also thrilled to tell me about why voice interaction is so important for technology companies to get right. “The stakes are really high for voice user interfaces, because voice is such a personal marker of social identity,” he says. Like many other Assistant team members I spoke with, Giangola often abbreviates the term voice user interface as VUI, pronounced “vooey,” in conversation. “Helen Keller said blindness separates people from things, and deafness separates people from people,” he says. “Voice is your place in society.”

His job also entails casting and coaching the actor Google hired to play Assistant’s voice. He plays me a clip of one studio session in which he worked with the voice actor behind Assistant to get her into character. (Google declined to reveal her identity.) In this particular scenario, Giangola played the role of a manager asking the actor how a recent interview with a potential hire went, a task Assistant can’t currently help with but might someday.

The actor playing Assistant replies in what seems like a characteristically Google way: “Well, he was on time, and he was wearing a beautiful tie.” Factual and upbeat, if a little odd. Her voice is nearly impossible to distinguish from that of the inanimate butler she’s portraying, except for a subtle break as she says the word tie, which reminds me she’s human. Which also reminds me that even a voice that sounds genuine isn’t all that useful if its speaker doesn’t understand the intricacies of spoken language. Tell Assistant “I’m lonely” and it will recite an elaborately crafted and empathic response that Krettek and others helped create. But tell it “I feel like no one likes me” and it responds that it does not understand.

There are more prosaic problems for Google and its competitors than decoding the fundamentals of speech. Engaging users in the first place is a big one. Google doesn’t typically make its usage statistics public, but according to a study last year by researcher Creative Strategies, people said they used voice features only rarely or sometimes: 70% for Siri and 62% for Google.

Privacy is another growing concern. Earlier this year, for example, ambient recordings from an Amazon Echo were submitted as evidence in an Arkansas murder trial, the first time data recorded by an artificial-intelligence-powered gadget was used in a U.S. courtroom. Devices like Echo and Google’s Home are always listening but don’t send information to their hosts unless specifically prompted–or in Assistant’s case, when someone says, ‘O.K., Google.’ But given that firms such as Amazon and Google profit from knowing as much about you as possible, the idea of placing Internet-connected microphones around the house is disquieting to many. Google says it clearly lays out what kind of data its gadgets collect on its website and points to the light on top of its Home speaker that glows to indicate when it’s actively listening.

And then there’s the difficulty of the underlying problem. Computers are still far from being able to detect the cues that make it possible to understand how a person may be feeling when making a request or asking a question. To do so, Assistant would need to learn from a huge amount of data that depicts the user’s voice in various emotional states. “Training data usually includes normal speech in relatively quiet settings,” says Jaime Carbonell, director of the Language Technologies Institute at Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Computer Science. “You don’t typically get people in highly stressful situations to provide data. It’s very difficult to collect data under all of these conditions.”

Getting more devices into more homes would help. On Oct. 4, in a splashy presentation, Google announced two new Home speakers, including a smaller, less expensive version and a higher-end device. But Amazon is still far ahead. The company’s Echo speaker will capture 70.6% of the voice-enabled speaker market in 2017, while Google will account for only 23.8%, according to eMarketer projections.

Germick doesn’t seem daunted, though. And he isn’t shy about Assistant’s shortcomings. When I ask him which artificial intelligence from science fiction he hopes Assistant evolves into, he doesn’t choose one of the super-advanced, all-knowing varieties like Jarvis in the Iron Man films or Samantha from the 2013 movie Her. He says he hopes to make Assistant like the perennially cheery character played by Ellie Kemper on Netflix’s Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. Despite having been held captive underground for 15 years and being systematically bamboozled, Kemper plays Kimmy as almost unnervingly able to find the bright side. “We talk a lot about her relentless optimism,” Germick says. “Just like she came out of the vault, we don’t always understand context, but we try to stay positive.” That’s the thing about personality: quirks can be part of the charm.

Correction: The original version of this story mischaracterized James Giangola’s previous work experience.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com