On a crisp fall day in Vienna, Austria, I received a private tour of the crypt below Michaelerkirche (St. Michael’s Church). Bernard, the young Austrian man who led me down the steep stone staircase, had perfect English delivered in an inexplicably deep Southern accent.

“Aye’ve been told my ax-sent is straynge be-fore,” he drawled, like a Confederate general.

Bernard explained that during the Middle Ages, when the members of the Hapsburg court attended St. Michael’s, there was a cemetery located directly outside, in the courtyard. But, as so often happened in larger European cities, the cemetery became overcrowded, “lay-urd with de-cay-ing bodies” — so overcrowded, in fact, that the neighbors (that is to say, the Emperor) complained of the stench. The cemetery was closed and a crypt constructed deep beneath St. Michael’s in the seventeenth century.

Many of the thousands of bodies buried in the crypt were laid to rest on beds of woodchips inside wooden coffins. The woodchips soaked up the fluids from decomposition. The dryness that followed this fluid absorption, in combination with drafts of cool air flowing through the crypt, caused a spontaneous natural mummification of the bodies.

Bernard shone a flashlight onto a man’s body, holding the beam on the spot where the lace bottom of his baroque-era wig clung to his taut grey skin. Down the row, past the typical stacks of bones and skulls found in charnel houses, the body of a woman was so well preserved that her nose still protruded outward from her face, some three hundred years after her death. Her delicate, articulated fingers lay crossed over her chest.

The church currently makes four of these crypt mummies available for public viewing. The questions visitors pose to Bernard should be obvious: “How did this mummification occur?” Or, “How did the church manage to beat the recent invasion of wooden coffin-devouring beetles from New Zealand?” (Answer: by installing air conditioning).

But what visitors, especially young visitors, really want to know is, “Are the bodies real?”

The question is posed as if the stacked bones and skulls, the rows of coffins, the rare mummies, could all be part of a spooky haunted-crypt attraction instead of the very history of the city in which they live.

At almost any location in any major city on Earth, you are likely standing on thousands of bodies. These bodies represent a history that exists, often unknown, beneath our feet. While a new Crossrail station was being dug in London in 2015, 3,500 bodies were excavated from a sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cemetery under Liverpool Street, including a burial pit from the Great Plague of 1665. To cremate bodies we burn fossil fuel, thus named because it is made of decomposed dead organisms. Plants grow from the decayed matter of former plants. The pages of my book are made from the pulp of raw wood from a tree felled in its prime. All that surrounds us comes from death, every part of every city, and every part of every person.

That autumn day in Vienna, my private tour of the crypt wasn’t private because I possess an exclusive all-access corpse card. The tour was private because I was the only person who showed up.

Outside, in the courtyard that was once an overcrowded cemetery, groups of schoolchildren swarmed. They waited impatiently to be herded into the Hofburg Palace to con- front the relics of the past, jewels and golden scepters and cloaks. In the church just across the courtyard, down some steep stone steps, there were bodies that could teach the children more than any scepter. Hard evidence that all who came before them have died. All will die someday. We avoid the death that surrounds us at our own peril.

Death avoidance is not an individual failing; it’s a cultural one. Facing death is not for the faint-hearted. It is far too challenging to expect that each citizen will do so on his or her own. Death acceptance is the responsibility of all death professionals — funeral directors, cemetery managers, hospital workers. It is the responsibility of those who have been tasked with creating physical and emotional environments where safe, open interaction with death and dead bodies is possible.

Nine years ago, when I began working with the dead, I heard other practitioners speak about holding the space for the dying person and their family. With my secular bias, “holding the space” sounded like saccharine hippie lingo. This judgment was wrong. Holding the space is crucial, and exactly what we are missing. To hold the space is to create a ring of safety around the family and friends of the dead, providing a place where they can grieve openly and honestly, without fear of being judged.

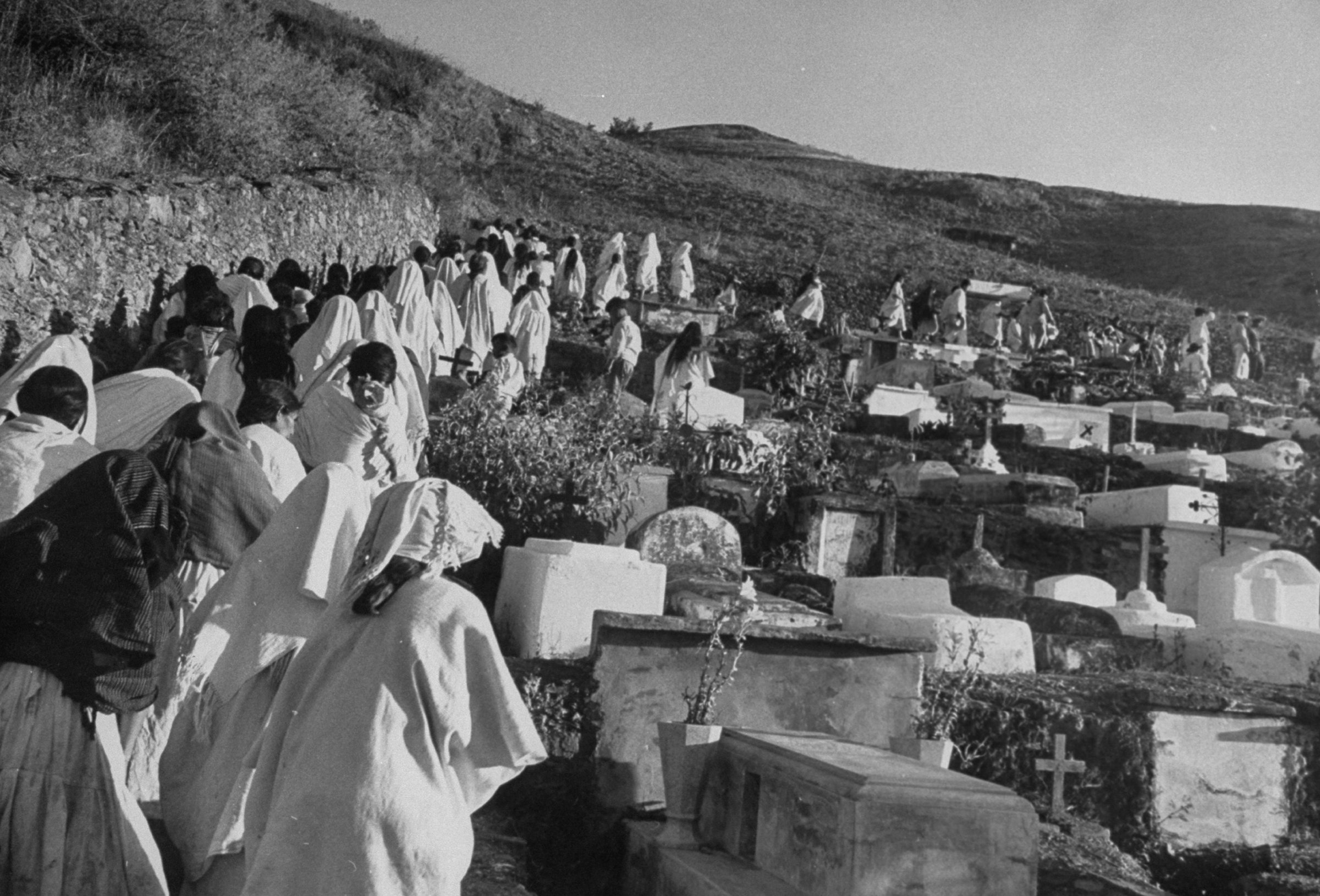

Everywhere I traveled I saw this death space in action, and I felt what it means to be held. At Ruriden columbarium in Japan, I was held by a sphere of Buddhas glowing soft blue and purple. At the cemetery in Mexico, I was held by a single wrought-iron fence in the light of tens of thousands of flickering amber candles. At the open-air pyre in Colorado, I was held within the elegant bamboo walls, which kept mourners safe as the flames shot high. There was magic to each of these places. There was grief, unimaginable grief. But in that grief there was no shame. These were places to meet despair face to face and say, “I see you waiting there. And I feel you, strongly. But you do not demean me.”

In our Western culture, where are we held in our grief? Perhaps religious spaces, churches, temples — for those who have faith. But for everyone else, the most vulnerable time in our lives is a gauntlet of awkward obstacles.

First come our hospitals, which are often perceived as cold, antiseptic horror shows. At a recent meeting, a longtime acquaintance of mine apologized for having been so hard to reach, but her mother had just died in a Los Angeles hospital. There had been an extended illness, and her mother spent her final weeks lying on a special inflatable mattress, designed to prevent the bedsores that can develop from long periods of immobility. After her death, the sympathetic nurses told my acquaintance that she could take the time she needed to sit with her mother’s body. After a few minutes, a doctor strode into the room. The family had never met this doctor before, and he did not choose to introduce himself. He walked over to her mother’s chart, read it briefly, and then leaned down and pulled the plug on the inflatable mattress. Her mother’s lifeless body sprang upward, jolting from side to side “like a zombie” as the air left the mattress. The doctor walked out, having not said a word. The family was far from held. As soon as their mother took her last breath, they were spat out.

Second, there are our funeral homes. An executive of Service Corporation International, the country’s largest funeral and cemetery company, admitted recently that “the industry was really built around selling a casket.” As fewer and fewer of us see value in placing Mom’s made-up body in a $7,000 casket and turn to simple cremations instead, the industry must find a new way to survive financially, by selling not a “funeral service” but a “gathering” in a “multisensory experience room.”

As a recent Wall Street Journal article explained: “Using audio and video equipment, the experience rooms can create the atmosphere of a golf course, complete with the scent of newly mowed grass, to salute the life of a golfing fanatic. Or it can conjure up a beach, mountain or football stadium.”

Perhaps paying several thousand dollars to hold a funeral in a faux “multisensory” golf course will make families feel held in their grief, but I have my doubts.

My mother recently turned seventy. One afternoon, as an exercise, I envisioned taking my mother’s mummified body out of the grave, as they do in Tana Toraja in Indonesia. Pulling her remains toward me, standing her up, looking her in the eyes years after her death — the thought no longer alarmed me. Not only could I handle such a task, I believe I would find solace in the ritual.

Holding the space doesn’t mean swaddling the family immobile in their grief. It also means giving them meaningful tasks. Using chopsticks to methodically clutch bone after bone and place them in an urn, building an altar to invite a spirit to visit once a year, even taking a body from the grave to clean and redress it: these activities give the mourner a sense of purpose. A sense of purpose helps the mourner grieve. Grieving helps the mourner begin to heal.

We won’t get our ritual back if we don’t show up. Show up first, and the ritual will come. Insist on going to the cremation, insist on going to the burial. Insist on being involved, even if it is just brushing your mother’s hair as she lies in her casket. Insist on applying her favorite shade of lipstick, the one she wouldn’t dream of going to the grave without. Insist on cutting a small lock of her hair to place in a locket or a ring. Do not be afraid. These are human acts, acts of bravery and love in the face of death and loss. I would be comfortable with my mother’s dead body precisely because I would be held. The ritual doesn’t involve sneaking into a cemetery in the dead of night to peek in on a mummy. The ritual involves pulling someone I loved, and thus my grief, out into the light of day. Greeting my mother, alongside my neighbors and family — my community standing next to me in support. Sunlight is the best disinfectant, they say. No matter what it takes, the hard work begins for the West to haul our fear, shame, and grief surrounding death out into the disinfecting light of the sun.

Excerpted from From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death by Caitlin Doughty. © 2017 by Caitlin Doughty. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com