When Jack Kerouac’s On the Road was released on Sept. 5, 1957 — 60 years ago this Tuesday — the first impression of TIME’s critic was that the book was “partly an ingenuous travel book, partly a collection of journalistic jottings about adventures that are known to everyone who has ever hitchhiked more than a hundred miles in the U.S.” And yet, even with that somewhat dubious characterization, it was clear that the work had something noteworthy within it.

Kerouac, working out of his mother’s house in Orlando, Fla., had finally put a literary face on the “beat generation,” a world with which the 35-year-old author was intimately familiar. “With his barbaric yawp of a book, Kerouac commands attention as a kind of literary James Dean,” the reviewer noted.

As TIME’s then explained, the plot was an opportunity for Kerouac to expound upon a new set of moral guidelines for young Americans:

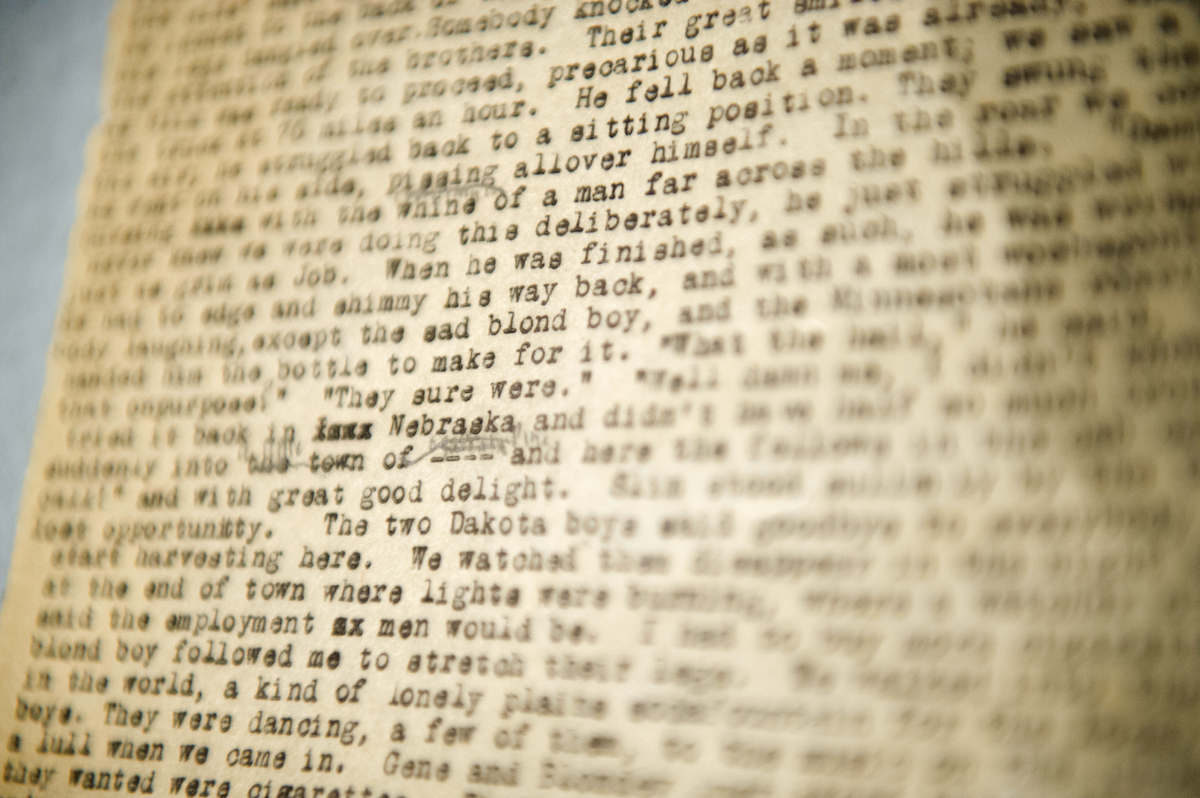

The story is set in the late 1940s, told in the first person by Sal Paradise, a budding writer given to ecstasies about America, hot jazz, the meaning of life, and marijuana. The book’s protagonist is Dean Moriarty (“a sideburned hero of the snowy West”), who has spent a third of his waking time in poolrooms, a third in jail, a third in public libraries, and is always shouting “Yes, yes, yes!” to every experience. Dean and Sal and their other buddies—Carlo Marx, the frenzied poet; Ed Dunkel, an amiable cipher; Remi Boncoeur, who has the second loudest laugh in San Francisco—are forever racing cross-country to meet one another. Their frantic reunions are curiously reminiscent of lodge and business conventions, with the same shouts of fellowship, hard drinking, furtive attempts at sexual dalliance—and, after a few days, the same boredom.

Then Sal’s pals are off again, by bus, on foot, by thumb, roaming the continent, feeling the wind of Wyoming nights and the heat of Texas days, looking for Moriarty’s never-to-be-found father or anyone’s sister, always expecting the ultimate in music or love or understanding around the next bend in the road. Excitement and movement mean everything. Steady jobs and homes in the suburbs are for the “squares.”

Dean Moriarty, a real gone kid in whom Sal sees traces of a “W. C. Fields saintliness,” is the only authentic proletarian in a basically timorous band of bourgeois rebels. Dean steals cars where the others are scarcely capable of filching a loaf of bread from an untended grocery. He takes women and abandons them, wrecks Cadillacs for the hell of it, deserts his friends. He talks a blue streak in a syntax-free jumble of metaphysics, hipster jargon, quotations from comic strips and animal gruntings. Describing the skills of a hot saxophonist, Dean cries: “Here’s a guy and everybody’s there, right? Up to him to put down what’s on everybody’s mind. He starts the first chorus, then lines up his ideas, people, yeah, yeah, but get it, and then he rises to his fate and has to blow equal to it. All of a sudden, somewhere in the middle of the chorus he gets it . . . Time stops. He’s filling empty space with the substance of our lives, confessions of his belly bottom strain, remembrance of ideas, rehashes of old blowing.”

It was Kerouac’s ability to “create a rationale” for what seemed to many Americans to be a senseless streak of rebellion among the nation’s youth that allowed On the Road to strike a chord even with readers who were not themselves attracted to the beat movement. That’s also part of the reason why, 60 years later, the book remains an iconic moment in American literature — even despite the later revelation that Kerouac himself did not drive.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com