A 110-year-old World War II veteran in Texas was able to remain in his home last year after his family raised nearly $200,000 online to pay for his nursing care. A Harvard-bound teen in Compton, Calif. put out a digital call for help and received $21,000 for textbooks and other expenses so that he could afford to attend the Ivy League school. In Detroit, residents raised more than $2,200 for a 74-year-old peanut vendor whose motorized bicycle, which he used to push his cart, was stolen.

These are just three among millions of Americans who have turned to sites like GoFundMe and YouCaring in recent years in the hopes that sharing details of their personal plights will mobilize strangers to help them. Crowdfunding — the practice of raising small amounts of money from a large number of donors online — was once the province of startups and political campaigns. But over the past five years, it has ballooned into a multi-billion-dollar charity industry, with donations going not to gadgets or causes but to individual people.

Since GoFundMe launched in 2010, more than 40 million individual donors have raised more than $4 billion, with the fastest growing category of requests in education. YouCaring, a similar site, has raised more than $800 million since 2011, largely for personal medical causes. According to a 2016 Pew Research Center survey, 22% of Americans have donated to a crowdfunding site like one of these.

This growth is fueled by the generosity of ordinary people and social media-driven campaigns — but it’s also driven by structural gaps that have left too many Americans one piece of bad luck away from financial hardship. More than 40% of Americans are not prepared to handle a sudden expense of $400 or more, like replacing a broken car engine or visiting an emergency room without insurance, according to a recent report by the Federal Reserve.

“People need help,” says GoFundMe CEO Rob Solomon, who left his job as a partner in a venture capital firm to take over the company in 2015. “People want to be empowered to help each other out. There’s a lot of need out there.”

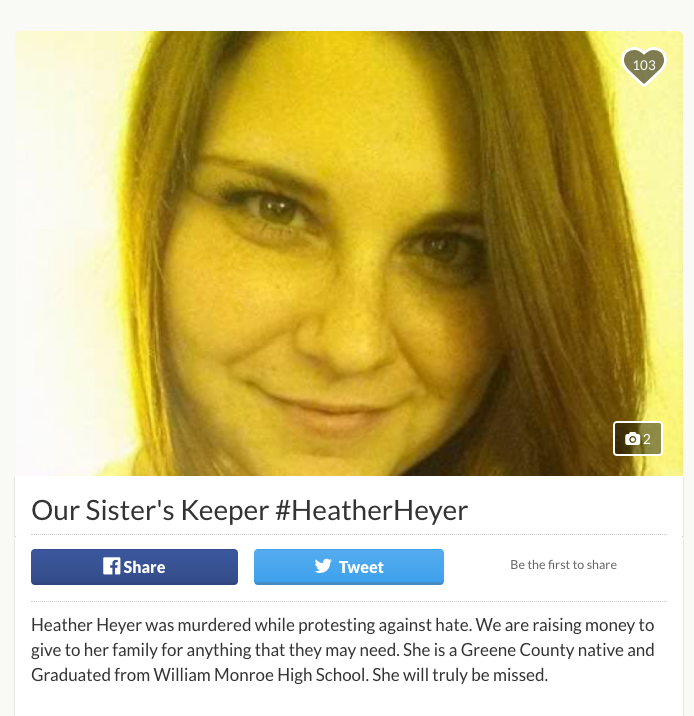

Crowdfunding has also become a new way to respond to disasters and public tragedies. After 32-year-old Heather Heyer was killed Aug. 12 in Charlottesville, Va. while protesting a white supremacy rally, a GoFundMe campaign quickly drew more than $220,000 in her memory. When Hurricane Harvey struck Texas on Aug. 25, about 850 GoFundMe campaigns launched in less than a week, bringing in a reported $4.5 million for causes ranging from caring for rescued pets to rebuilding destroyed homes.

Online crowdfunding began as a way to serve much less personal causes. Indiegogo and Kickstarter, which launched in 2008 and 2009, allowed entrepreneurs and small businesses to get funding for inventions and projects like the Coolest Cooler — a high-tech drink container with a built-in blender, waterproof bluetooth speaker and a USB charger — and a movie reboot of the beloved Veronica Mars television franchise.

Sites like GoFundMe and YouCaring saw a chance to tap this impulse, and built user-friendly interfaces that feel more like social networks than traditional charity websites, with trending topics and colorful videos. GoFundMe’s founders, Brad Damphousse and Andrew Ballester, had previously founded Paygr, a site where neighbors can buy and sell items or services, and their new company extended the support of neighbors to a much broader community. One of GoFundMe’s early successes came after the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, when more than 34,000 donors raised more than $2 million for those who were seriously injured.

GoFundMe’s founders also saw a business opportunity. GoFundMe takes 5% of what every campaign raises, in addition to passing along a credit card processing fee to donors. YouCaring, in contrast, only charges the credit card fee and is supported by donations. Neither company releases financial information, but GoFundMe says nine campaigns in the past year and a half have topped $1 million — which would mean more than $450,000 for GoFundMe, for those large campaigns alone.

While no one disputes that this new fundraising model has helped hundreds of thousands of people, it’s not without its challenges. The most successful crowdfunding campaigns convey a dramatic story of heartbreak or hope, complete with photos and personal details. But many people in need don’t have a story that fits neatly into a compelling narrative, or the digital savvy to package it that way. And then there’s the randomness of what the internet elevates and discards. For every case like the Texas World War II veteran, who raised far more than his family had ever hoped, there are dozens of campaigns that never catch on, leaving people struggling.

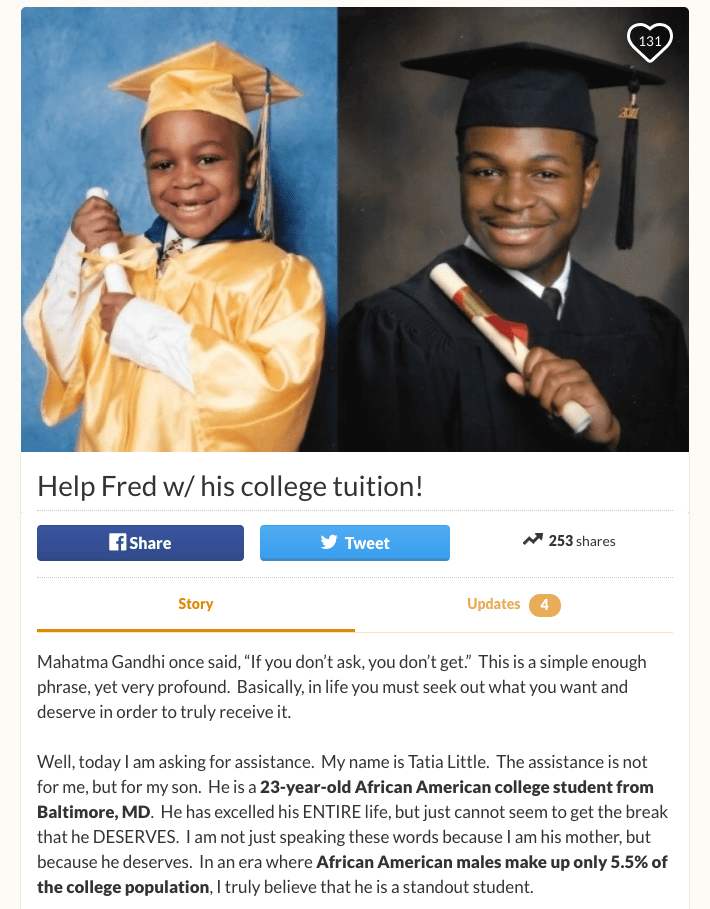

The decision to post a personal story on a crowdfunding site can be a difficult one. “I’ve always been very independent. I’ve always been everybody’s go-to person. You have to humble yourself,” says Tatia Little, a single mother in Maryland who raised about $6,700 of her $20,000 goal to get her son through art school. “I don’t have any other way to do this, and we can’t not do it.”

“It is what it is,” adds Little, 50, who works at the U.S. Social Security Administration. “You think, ‘What are they going to think of me?’ You get to a point where it doesn’t matter.’”

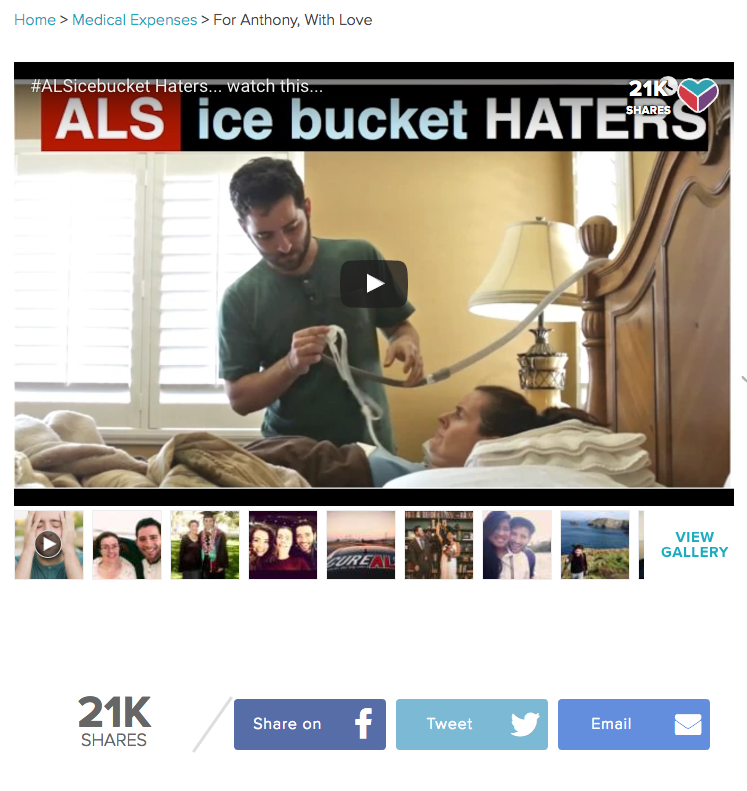

Anthony Carbajal reached that point in the summer of 2014. As the Ice Bucket Challenge swept the internet to raise money for ALS research, the 26-year-old was caring for his mother, who had been diagnosed with the progressive neurological disease, when he learned that he, too, had ALS.

The shaken Carbajal, a wedding photographer from California, recorded a video in his home describing his fears of one day being fully paralyzed from the incurable condition. “I’ve been so terrified of ALS my entire life because it runs in my family,” he says, before breaking down and turning away.

He posted the moving video at the top of his YouCaring page, where he asked for help paying for costs Medicaid wouldn’t cover, like making his home wheelchair accessible. He raised more than $266,000 in nine months and appeared on The Ellen DeGeneres Show, where the TV host gave Carbajal $100,000 in buckets of cash — half for ALS research and the other half for his family.

“I didn’t know how my mom and I would pay for our medical needs,” Carbajal told TIME recently. “I thought that would be my demise.”

Carbajal can no longer lift his arms or fully hold his neck up, and he is slowly losing his ability to walk and breathe. His mother is now fully paralyzed, but the two count their blessings.

“We’re one of the lucky ones,” says Carbajal, who is now married and lives in an accessible home purchased with help from YouCaring’s donors. “We have a home. My mom has a caregiver in the home she got married in. My life would be completely different without crowdfunding.”

Crowdfunding is still dwarfed by traditional charities, which bring in hundreds of billions of dollars each year in the U.S. But mainstays like the American Red Cross and Salvation Army are taking note of the medium’s appeal to a younger generation of donors. As direct-mail and telethon contributors age, century-old nonprofits see an opportunity to draw new digital funding streams from crowdfunding sites.

“We wouldn’t have been here this long if we didn’t continue to adapt and evolve,” says Jennifer Elwood, vice president of consumer marketing and fundraising at the Red Cross, which has worked with CrowdRise, a site acquired by GoFundMe last year. CrowdRise’s supporters are an average 45 to 55 years old, compared to the 70-to-80-year-old donors who respond to the Red Cross’ direct-mail campaigns. “Part of our DNA is meeting people where they’re at and making sure we’re relevant,” Elwood says.

The Salvation Army, too, is taking a closer look at crowdfunding. When flooding hit Louisiana last summer, damaging thousands of homes and businesses, donors gave $4 million to the Salvation Army’s relief efforts, which the organization said was not enough to meet the needs on the ground. In contrast, GoFundMe users raised more than $11 million for more than 6,000 campaigns related to the flood. The disparity was enough to prompt the Salvation Army to consider using crowdfunding campaigns in the future, according to Ron Busroe, the group’s national secretary for community relations and development.

Charitable donations in the U.S. have steadily increased since 2010, reaching a record high of $390 billion in 2016, a figure that includes donations given to traditional charities and some crowdfunding campaigns, according to the Giving USA Foundation. That’s a dramatic increase from the roughly $134 billion raised in 1976, adjusted for inflation, as well as the $307 billion donated in 2009.

“There is a very significant role that crowdfunding is playing,” says Una Osili, associate dean for research and international programs at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, which works with Giving USA to track charitable giving. “It’s increasing the overall amount, but it’s also broadening who is participating. It has the potential to draw new donors and make giving more inclusive.”

Still, crowdfunding comes with risks that aren’t present when giving to an established nonprofit. Many believed Jennifer Flynn Cataldo in January 2016 when the 37-year-old Alabama woman claimed she had terminal cancer and created a GoFundMe page for a final Disney vacation. Cataldo, who does not have cancer, pocketed more than $10,000 before she was found out, federal prosecutors said. In May, she was indicted on fraud charges.

GoFundMe says the site verifies the identity of all campaign organizers and employs a team to monitor the platform for fraud. Campaigns involving a misuse of funds make up less than a tenth of one percent of all the funding requests on the site, and when they do happen, the money is returned in full to every donor.

Crowdfunding also raises thorny tax questions. Donations to individuals are not tax-deductible, as donations to traditional charities are. And while the IRS says those who receive money from crowdfunding can claim it as an untaxed gift, a handful of crowdfunders report receiving tax bills anyway. Money raised from crowdfunding can also affect a family’s eligibility for public assistance.

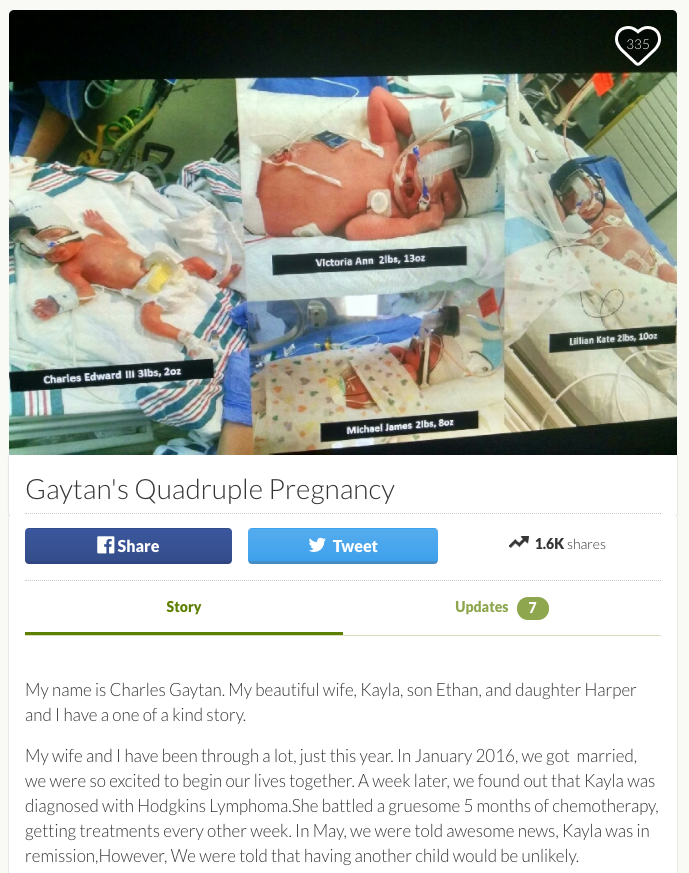

For Kayla Gaytan, the benefits of crowdfunding far outweighed any potential risks. The 30-year-old Kentucky mom and her husband Charles Gaytan, an active-duty military police officer at Fort Campbell, posted their plea for help on GoFundMe last September, when Kayla, a Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivor, was five months pregnant with quadruplets. Her cancer was in remission, but doctors had given her only a 50% chance of living to see the babies enter kindergarten.

The Gaytans set their request at $5,000 to help pay for diapers, food and everyday expenses. Local media outlets picked up their story, and as it spread rapidly on Facebook, it became national news. In just a few months, more than 17,000 people were moved to contribute more than $1 million.

“It renewed our faith in humanity,” Gaytan says.

The family’s struggles, though, were not over. Gaytan’s cancer returned in the seventh month of her pregnancy and she was forced to deliver the quadruplets early so she could resume treatment. The babies — girls Lillian and Victoria, and boys Charles III and Michael — are all healthy, but Gaytan’s cancer has stopped responding to chemotherapy, so she is now preparing for a stem cell transplant in the hope of finding a cure.

The couple has put away most of the money they received from GoFundMe in a trust for their children’s college tuitions. They have used the rest for everyday necessities, relieving at least some of their short-term worries and allowing them to enjoy the moments they have with the quadruplets and their two grade-school kids.

“It makes me feel really good because let’s face it, I may not be here in eight to 10 years. Maybe not in five years,” Gaytan says. “If for some reason my husband wasn’t able to work, that would be OK for a little while. That would be one less worry they’re going to have.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com