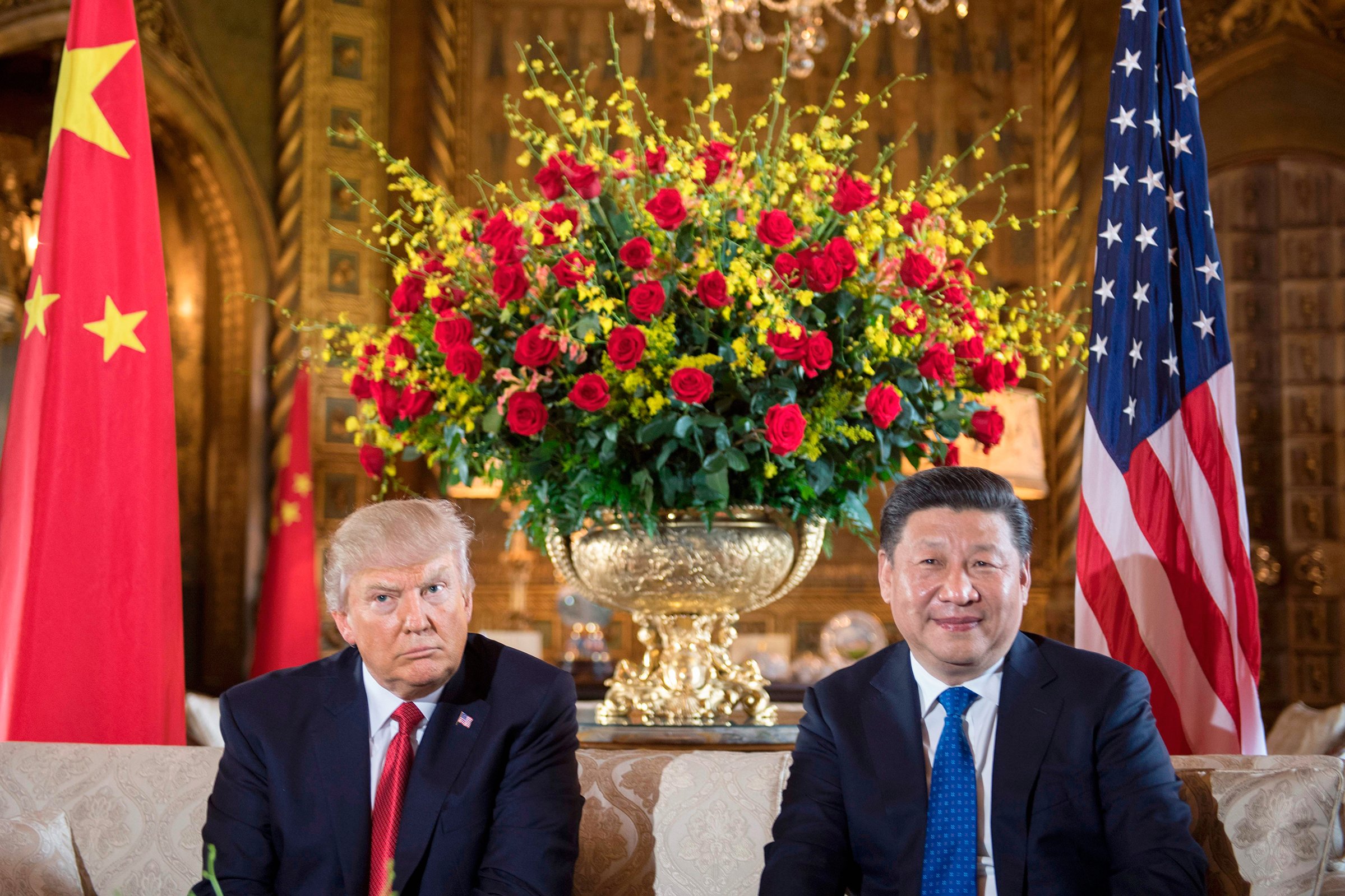

President Donald Trump was ready to wage war in Asia this week — but not against North Korea and not with conventional weapons. Instead, it was China at risk and of a trade war. The White House had repeatedly warned that the Middle Kingdom’s persistent misbehavior would lead to more U.S. pressure on the superpowers’ trade relationship, and it seemed finally ready to act. Yet China’s cooperation on U.N. Security Council sanctions against North Korea earlier in August seems to have bought Beijing some time. Instead of announcing retaliatory polices that could launch an economic skirmish as many expected, on Aug. 14 President Trump announced a broad investigation into China’s suspected theft of American intellectual property.

Trump’s announcement keeps the pressure on China while allowing him the space he needs to plan his next move. And though many have warned that a conflict over commerce would quickly escalate and badly damage both sides, it’s clear that the U.S. would win a trade war with the emerging-market giant.

Why? For one, China’s vulnerabilities are far greater. The crudest measure of this is the $300 billion — plus trade deficit that Trump has complained so much about. In 2016, U.S. exports to China totaled $115.6 billion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, while China’s exports to the U.S. totaled $462.6 billion. Beijing can cause pain for American companies and consumers, particularly in sectors like agriculture where U.S. firms employ few Chinese workers. But international commerce still supports tens of millions of jobs in China. Although it is less important to the economy than it was, trade accounts for almost 40% of Chinese GDP vs. less than 30% in the U.S.

Debt is another source of Chinese weakness. Its economy has been slowing down for several years, and its government has tried to manage the pace of deceleration by providing large amounts of credit. Heavy spending by the government and state-owned companies have pushed debt levels to dangerous new heights. In June the Institute of International Finance, a Washington-based trade group, estimated that China’s total debt is now more than 304% of GDP — an unprecedented figure for a country at China’s low level of income per person.

China has also lost some of its most important advantages. Thanks to technology, labor alone no longer generates the same amount of capital it once did. At the same time, Chinese labor is getting more expensive. Consulting firm Oxford Economics estimated recently that China’s unit labor costs were just 4% lower than those in the U.S. It’s now cheaper to pay factory workers in Japan than in China, per unit of output.

This is an especially delicate moment for China, as a once-in-five-years Party Congress this fall should replace five of seven members of the country’s highest decisionmaking body and many more at other levels of its central government. It’s a moment when senior Communist Party officials want to project calm confidence, shying away from fights they might not win. That said, if Chinese President Xi Jinping begins to feel like he’s losing face, it will be almost impossible for him to ignore Trump’s direct hits.

But there’s a catch for the Trump team. If you want to be sure the near-term pain a trade battle would impose on U.S. workers will prove worthwhile in the long run, you’d better have allies — both political and military. Yet President Trump passed on an opportunity to strengthen ties with a number of Asian partners when he walked away from the enormous Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal. He encouraged NATO members to hedge their bets on Washington by allowing them to question his commitment to the Atlantic alliance. By walking away from the Paris climate accord, he allowed China’s Xi to claim the high ground on global environmental activism.

President Trump must also understand that China will do its best to target U.S. companies and industries based in states with high concentrations of voters that are part of his political base. China’s leaders can read an electoral map, and they know how to hit Trump where it hurts most.

So, yes, the U.S. can win a trade war with China. That doesn’t make it a good idea.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com