With the usual mix of anticipation and apprehension, Kaitlyn Johnson is getting ready to go to her first summer camp. She’s looking forward to meeting new friends and being able to ride horses, swim and host tea parties. She’s also a little nervous and a little scared, like any 7-year-old facing her first sleepaway camp.

But the wonder is that Kaitlyn is leaving the house for anything but a medical facility. Diagnosed with leukemia when she was 18 months old, her life has been consumed with cancer treatments, doctors’ visits and hospital stays.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is the most common cancer among young children, accounting for a quarter of all cancer cases in kids, and it has no cure. For about 85% to 90% of children, the leukemia can, however, be effectively treated through chemotherapy.

If it is not eliminated and comes back, it is, more often than not, fatal. Rounds of chemotherapy can buy patients time, but as the disease progresses, the periods of remission get shorter and shorter. “The options for these patients are not very good at all,” says Dr. Theodore Laetsch, a pediatrician at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

When Kaitlyn’s cancer wasn’t controlled after three years and round after round of chemotherapy drugs, her doctors had little else to offer. “They said, ‘This did nothing, it didn’t touch it,'” says Kaitlyn’s mother Mandy, a dental assistant from Royce City, Texas. “My stomach just dropped.” Kaitlyn could receive a bone-marrow transplant, but only about half of those procedures are successful, and there was a good chance that she would reject the donor cells. If that happened, her chances of surviving were very small.

In a calculated gamble, her doctors suggested a radical new option: becoming a test subject in a trial of an experimental therapy that would, for the first time, use gene therapy to train a patient’s immune system to recognize and destroy their cancer in the same way it dispatches bacteria and viruses. The strategy is the latest development in immunotherapy, a revolutionary approach to cancer treatment that uses a series of precision strikes to disintegrate cancer from within the body itself. Joining the trial was risky, since other attempts to activate the immune system hadn’t really worked in the past. Mandy, her husband James and Kaitlyn traveled from their home in Texas to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), where they stayed in a hotel for eight weeks while Kaitlyn received the therapy and recovered. “The thought crossed my mind that Kaitlyn might not come home again,” says Mandy. “I couldn’t tell you how many times I would be in the bathroom at the hospital, spending an hour in the shower just crying, thinking, What are we going to do if this doesn’t help her?”

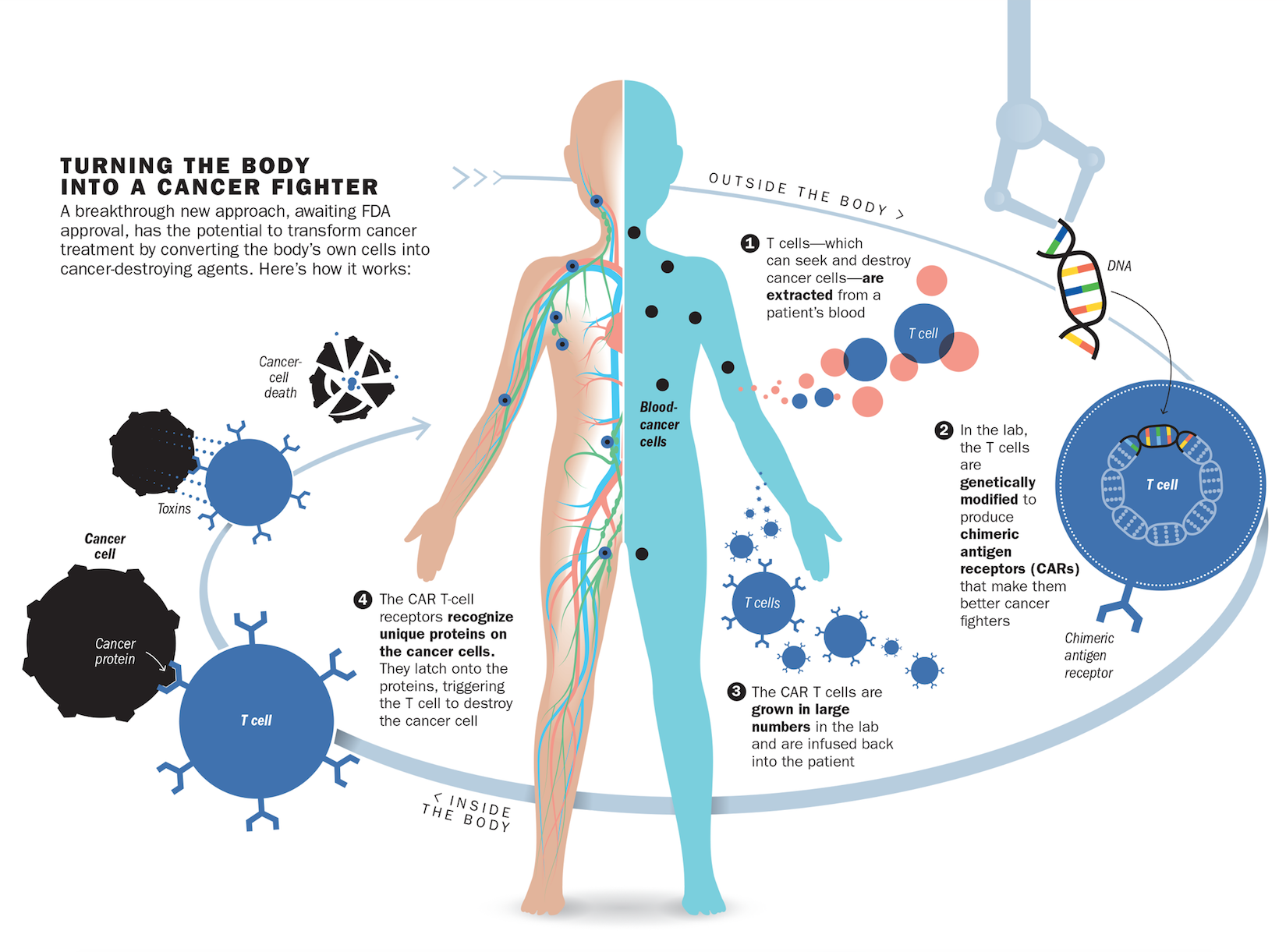

But it did. After receiving the therapy in 2015, the cancer cells in Kaitlyn’s body melted away. Test after test, including one that picks up one cancer cell in a million, still can’t detect any malignant cells lurking in Kaitlyn’s blood. What saved Kaitlyn was an infusion of her own immune cells that were genetically modified to destroy her leukemia. “You take someone who essentially has no possibility for a cure–almost every single one of these patients dies–and with [this] therapy, 90% go into remission,” says Dr. David Porter, director of blood and bone-marrow transplantation at the University of Pennsylvania. Such radical immune-based approaches were launched in 2011 with the success of intravenous drugs that loosen the brakes on the immune system so it can see cancer cells and destroy them with the same vigor with which they attack bacteria and viruses. Now, with the genetically engineered immune cells known as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells that were used in Kaitlyn’s study, doctors are crippling cancer in more precise and targeted ways than surgery, chemotherapy and radiation ever could. While the first cancer immunotherapies were broadly aimed at any cancer, experts are now repurposing the immune system into a personalized precision treatment that can not only recognize but also eliminate the cancer cells unique to each individual patient.

What makes immune-based therapies like CAR T cell therapy so promising–and so powerful–is that they are a living drug churned out by the patients themselves. The treatment isn’t a pill or a liquid that has to be taken regularly, but a one-hit wonder that, when given a single time, trains the body to keep on treating, ideally for a lifetime.

“This therapy is utterly transformative for this kind of leukemia and also lymphoma,” says Stephan Grupp, director of the cancer immunotherapy program at CHOP and one of the lead doctors treating patients in the study in which Kaitlyn participated.

Eager to bring this groundbreaking option to more patients, including those with other types of cancers, an advisory panel for the Food and Drug Administration voted unanimously in July to move the therapy beyond the testing phase, during which several hundred people have been able to take advantage of it, to become a standard therapy for children with certain leukemias if all other treatments have failed. While the FDA isn’t obligated to follow the panel’s advice, it often does, and it is expected to announce its decision in a matter of weeks.

Across the country, doctors are racing to enroll people with other cancers–breast, prostate, pancreatic, ovarian, sarcoma and brain, including the kind diagnosed in Senator John McCain–in hundreds of trials to see if they, too, will benefit from this novel approach. They are even cautiously allowing themselves to entertain the idea that this living drug may even lead to a cure for some of these patients. Curing cancers, rather than treating them, would result in a significant drop in the more than $120 billion currently spent each year on cancer care in the U.S., as well as untold suffering.

This revolutionary therapy, however, almost didn’t happen. While the idea of using the body’s immune cells against cancer has been around for a long time, the practical reality had proved daunting. Unlike infection-causing bacteria and viruses that are distinctly foreign to the body, cancer cells start out as healthy cells that mutate and grow out of control, and the immune system is loath to target its own cells.

“Only a handful of people were doing the research,” says Dr. Carl June, director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center and the scientist who pioneered the therapy. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, June is all too familiar with the devastating effects of cancer, having lost his first wife to ovarian cancer and battled skin cancer himself. Trial after trial failed as reinfusions of immune cells turned out to be more of a hit-or-miss endeavor than a reliable road to remission.

After spending nearly three decades on the problem, June zeroed in on a malignant fingerprint that could be exploited to stack the deck of a cancer patient’s immune system with the right destructive cells to destroy the cancer.

In the case of leukemias, that marker turned out to be CD19, a protein that all cancerous blood cells sprout on their surface. June repurposed immune cells to carry a protein that would stick to CD19, along with another marker that would activate the immune cells to start attacking the cancer more aggressively once they found their malignant marks. Using a design initially developed by researchers at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital for such a combination, June and his colleague Bruce Levine perfected a way to genetically modify and grow these cancer-fighting cells in abundance in the lab and to test them in animals with leukemia. The resulting immune platoon of CAR T cells is uniquely equipped to ferret out and destroy cancer cells. But getting them into patients is a complex process. Doctors first remove a patient’s immune cells from the blood, genetically tweak them in the lab to carry June’s cancer-targeting combination and then infuse the modified cells back into the patient using an IV.

Because these repurposed immune cells continue to survive and divide, the therapy continues to work for months, years and, doctors hope, perhaps a lifetime. Similar to the way vaccines prompt the body to produce immune cells that can provide lifelong protection against viruses and bacteria, CAR T cell therapy could be a way to immunize against cancer. “The word vaccination would not be inappropriate,” says Dr. Otis Brawley, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society.

June’s therapy worked surprisingly well in mice, shrinking tumors and, in some cases, eliminating them altogether. He applied for a grant at the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health to study the therapy in people from 2010 to 2011. But the idea was still so new that many scientists believed that testing it in people was too risky. In 1999, a teenager died days after receiving an experimental dose of genes to correct an inherited disorder, and anything involving gene therapy was viewed suspiciously. While such deaths aren’t entirely unusual in experimental studies, there were ethical questions about whether the teenager and his family were adequately informed of the risks and concerns that the doctor in charge of the study had a financial conflict of interest in seeing the therapy develop. Officials in charge of the program acknowledged that important questions were raised by the trial and said they took the questions and concerns very seriously. But the entire gene-therapy program was shut down. All of that occurred at the University of Pennsylvania–where June was. His grant application was rejected.

It would take two more years before private funders–the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and an alumnus of the university who was eager to support new cancer treatments–donated $5 million to give June the chance to bring his therapy to the first human patients.

The date July 31 has always been a milestone for Bill Ludwig, a retired corrections officer in New Jersey. It’s the day that he joined the Marines as an 18-year-old, and the day, 30 years later, that he married his wife Darla.

It was also the day he went to the hospital to become the first person ever to receive the combination gene and CAR T cell therapy, in 2010. For Ludwig, the experimental therapy was his only remaining option. Like many people with leukemia, Ludwig had been living on borrowed time for a decade, counting the days between the chemotherapy treatments that would hold the cancer in his blood cells at bay for a time. Inevitably, like weeds in an untended garden, the leukemia cells would grow and take over his blood system again.

But the periods of reprieve were getting dangerously short. “I was running out of treatments,” says Ludwig. So when his doctor mentioned the trial conducted by June and Porter at the University of Pennsylvania, he didn’t hesitate. “I never thought that the clinical trial was going to cure me,” he says. “I just wanted to live and to continue to fight. If there was something that would put me into the next month, still breathing, then that’s what I was looking for.”

When Ludwig signed the consent form for the treatment, he wasn’t even told what to expect in terms of side effects or adverse reactions. The scientists had no way of predicting what would happen. “They explained that I was the first and that they obviously had no case law, so to speak,” he says. So when he was hit with a severe fever, had difficulty breathing, showed signs of kidney failure and was admitted to the intensive care unit, he assumed that the treatment wasn’t working.

His condition deteriorated so quickly and so intensely that doctors told him to call his family to his bedside, just four days after he received the modified cells. “I told my family I loved them and that I knew why they were there,” he says. “I had already gone and had a cemetery plot, and already paid for my funeral.”

Rather than signaling the end, Ludwig’s severe illness turned out to be evidence that the immune cells he received were furiously at work, eliminating and sweeping away the huge burden of cancer cells choking up his bloodstream. But his doctors did not realize it at the time.

It wasn’t until the second patient, Doug Olson, who received his CAR T cells about six weeks after Ludwig, that Porter had a eureka moment. When he received the call that Olson was also running a high fever, having trouble breathing and showing abnormal lab results, Porter realized that these were signs that the treatment was working. “It happens when you kill huge amounts of cancer cells all at the same time,” Porter says. What threw him off initially is that it’s rare for anything to wipe out that much cancer in people with Ludwig’s and Olson’s disease. June and Porter have since calculated that the T cells obliterated anywhere from 2.5 lb. to 7 lb. of cancer in Ludwig’s and Olson’s bodies. “I couldn’t fathom that this is why they both were so sick,” says Porter. “But I realized this is the cells: they were working, and working rapidly. It was not something we see with chemotherapy or anything else we have to treat this cancer.”

Ludwig has now been in remission for seven years, and his success led to the larger study of CAR T cell therapy in children like Kaitlyn, who no longer respond to existing treatments for their cancer. The only side effect Ludwig has is a weakened immune system; because the treatment wipes out a category of his immune cells–the ones that turned cancerous–he returns to the University of Pennsylvania every seven weeks for an infusion of immunoglobulins to protect him from pneumonia and colds. Olson, too, is still cancer-free.

While the number of people who have received CAR T cell therapy is still small, the majority are in remission. That’s especially encouraging for children, whose lives are permanently disrupted by the repeated cycles of treatments that currently are their only option. “It’s a chance for these kids to have a normal life and a normal childhood that doesn’t involve constant infusions, transfusions, infections and being away from their home, family and school,” says Dr. Gwen Nichols, chief medical officer of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

The hope is that while CAR T cell therapy will at first be reserved for people who have failed to respond to all standard treatments, eventually they won’t have to wait that long. As doctors learn from pioneers like Kaitlyn, Ludwig and Olson, they will have more confidence in pushing the therapy earlier, when patients are stronger and the cancer is less advanced–perhaps as a replacement for or in combination with other treatments.

The severe immune reaction triggered by the therapy remains a big concern. While it can be monitored in the hospital and managed with steroids or antibodies that fight inflammation, there have been deaths in other trials involving CAR T cells. One drug company put one of its studies on hold due to the toxic side effects. “I am excited by CAR T therapy, but I’m also worried that some people might get too excited,” says the American Cancer Society’s Brawley. “It’s important that we proceed slowly and do this meticulously so that we develop this in the right way.”

For now, CAR T cells are expensive–some analysts estimate that each patient’s batch of cells would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars–because they require a bespoke production process. If approved, Novartis, which licensed the technology from the University of Pennsylvania, will provide the therapy in about 35 cancer centers in the U.S. by the end of the year. Other companies are already working toward universal T cells that could be created for off-the-shelf use in any patient with cancer. “This is just the beginning,” says June.

Since Ludwig’s cancer has been in remission, he and his wife have packed their RV and taken the vacations they missed while he was a slave to his cancer and chemotherapy schedule. This year, they’re visiting Mount Rushmore, Grand Teton National Park and Yellowstone National Park before taking their granddaughter to Disney World in the fall. “When they told me I was cancer-free, it was just like someone said, ‘You won the lottery,'” he says. “If somebody else with this disease has the chance to walk in my shoes and live past it, that would be the greatest gift for me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com