To the men and women of the Trump White House–the curious, the hopeful, the desperate and the dubious–the all-hands summons was a little out of the ordinary.

It invited everyone to a meeting the next day in an unusual place: not a room in the cramped West Wing or the much larger South Court Auditorium, which is typically used for such sessions, but the quieter marbled entryway of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next to the White House. After almost 200 days of infighting, leaks and operatic staff shake-ups, morale was running a bit thin. Hundreds of people, including dozens who have been exiled from the West Wing for a sorely needed renovation, turned up to meet the new boss.

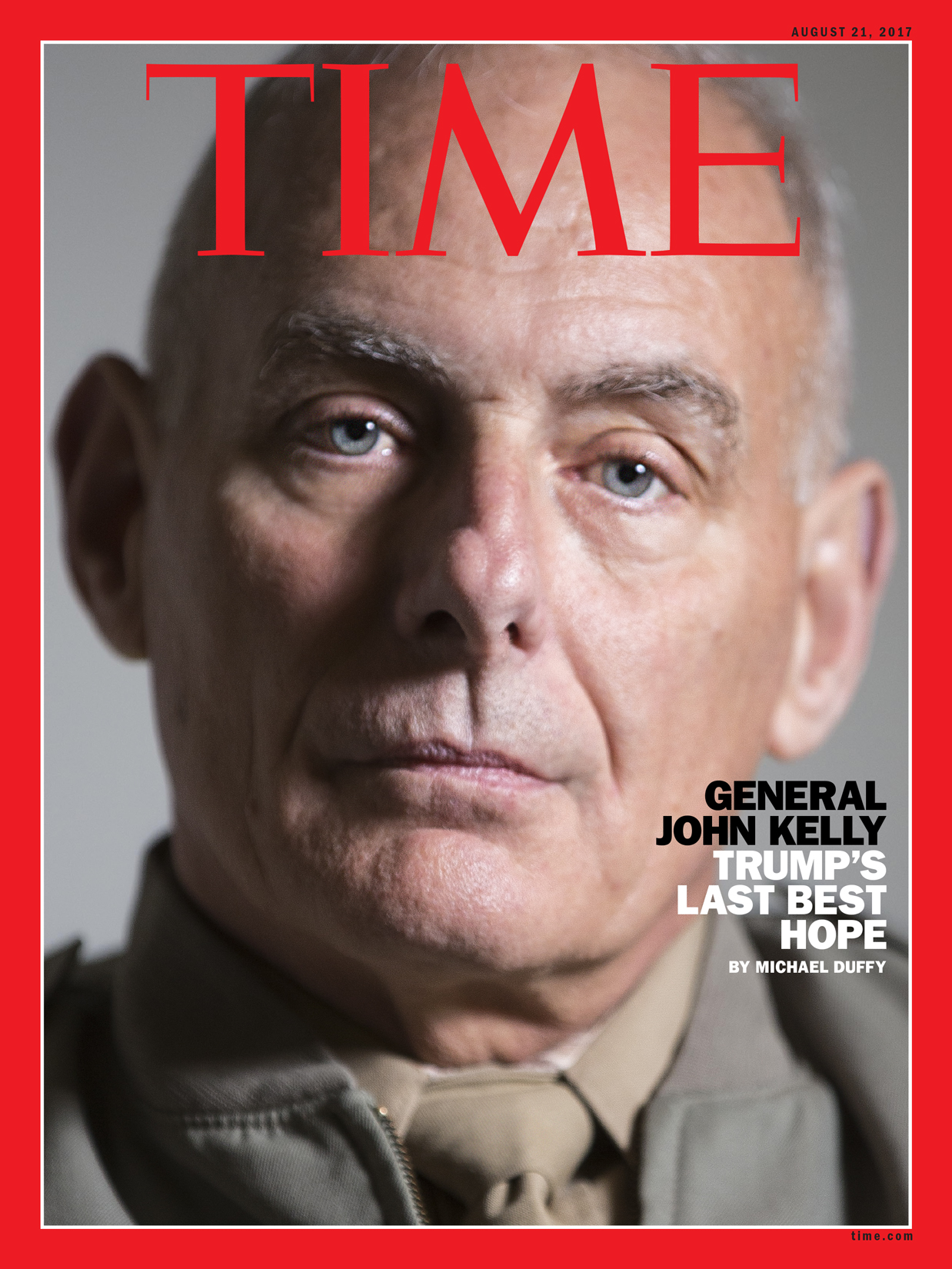

No introduction was needed. John Kelly simply stepped to the microphone and said, “Hi. Nice to meet you. I’m from Boston.” As the President’s son-in-law Jared Kushner and other senior aides watched from the wings, the retired four-star Marine general then rallied the embattled troops and laid down new rules of engagement. He urged his staff to stop the infighting and set their egos and agendas (and any leaking) aside. With a nod to the Marine credo–God, Country, Corps–he told his audience that they must start serving a hierarchy that put the nation, and not the President, first: “Country, President, Self,” he said.

So began a new era at Donald Trump’s White House, one that might be his best, or last, chance for success. Almost overnight, Kelly shut the always-open door to the Oval Office, sent hangers-on back to their desks, fired the combustible communications director Anthony Scaramucci and told all the leaders of all the many White House factions to report to him, not to the President. No one knows whether Kelly will succeed, how long he might last or if the general’s starched-shirt discipline will be rejected by the client. Early results were mixed, and skeptics are not hard to find. But Kelly clearly arrived with a mission: to fix a broken system that the nation and the world depends on every day to keep the ship called Earth in the middle of the channel.

Of course, almost any new order is better than the chaos that reigned in the White House before July 31. “It’s at rock bottom,” said one White House aide of the mood when Kelly took over. That doesn’t mean brighter days ahead. “Well, with this White House, it could always get worse.”

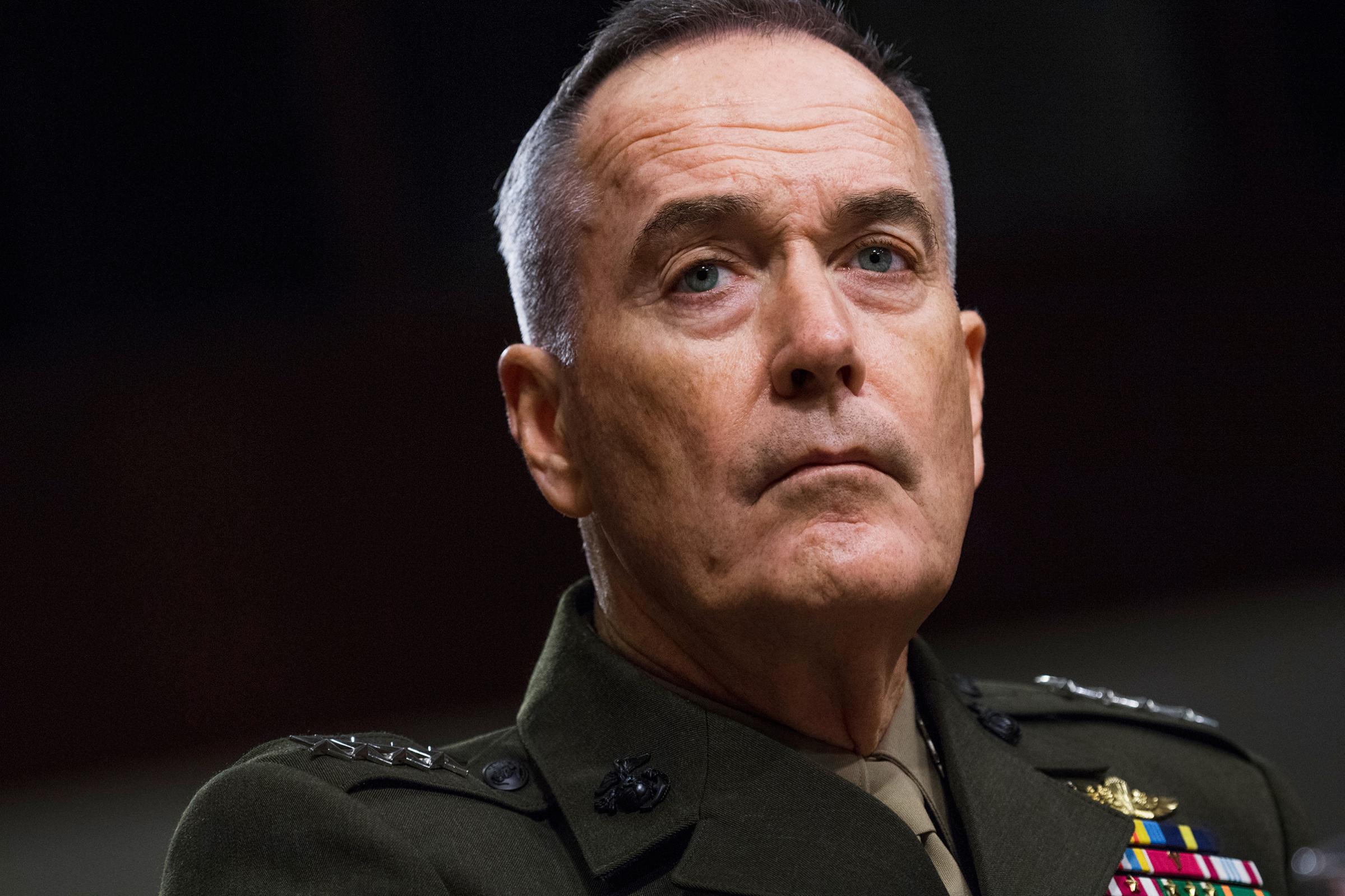

But under Kelly, 67, that seems unlikely, both because Kelly won’t permit it and because Trump, who defers to virtually no one, shows a clear preference for, and deference to, the military brass. It’s a bit of a mystery why. Perhaps because he went to a military academy for five years, or because he imagines that they will do whatever he says, or because he just likes tough guys with a killer instinct, Trump likes generals. Rarely in U.S. history has a clutch of senior brass played such an outsize role in the affairs of state as they do now. The President’s chief of staff, his Defense Secretary James Mattis and his National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster are all either active-duty or retired generals. What makes the arrangement all the more interesting is that the three men are not only friends but longtime allies. Two of the three are Marines, and when you add Joseph Dunford, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs (who, with Kelly, served under Mattis), it is safe to say the scrappy Marine Corps has never had so much clout in the chain of command.

The deep bonds and know-how of that team may have already done the nation a great service. This summer, as the threats from North Korea increased while confusion dominated in the White House, the generals quietly launched a mission of their own. Mattis, McMaster and Dunford (as well as Secretary of State Rex Tillerson) were concerned enough about the conduct of foreign policy to work together to convince a skeptical Kelly to become chief of staff. Their argument: unless someone else takes over, this White House cannot handle a real crisis. Which means that when Trump asked Kelly for the third time to be his chief of staff, it wasn’t just a job offer. It was a call of duty.

Friends say that, almost to a person, John Francis Kelly is defined by his blue collar roots in Boston, where he was born in 1950 and where men of his generation and class proceeded directly from getting their draft notices to taking their physicals. If they passed that test, they immediately joined the Marine Corps. This tradition remains Kelly’s lodestar. “In the America I grew up in,” he said in a 2016 Marine interview commemorating his career, “every male was a veteran–my dad, my uncles, all the people on the block.” It was a tradition Kelly passed on to his kids. His two sons became Marines, and his daughter serves in the FBI.

An adventurous kid, Kelly hitchhiked across the U.S. as a teen and rode an empty boxcar back east before his 16th birthday, and then joined the Merchant Marine to see the world (his first ship delivered 10,000 tons of beer to Vietnam). In 1970, he enlisted in the Marines–a move that would endear him to many recruits he would one day lead–but that only got him as far as Camp Lejeune. “I was a grunt,” he recalled. “I wasn’t committed to a career. I wanted to go to college and come back and be an officer.” So after two years at Lejeune, he entered the University of Massachusetts in Boston, graduated in 1976 as a commissioned officer and began to climb the Corps’ small but fiercely competitive leadership ladder.

It was a legendary run. He served on carriers and did stints at Quantico, Camp Pendleton, the National War College in Washington and the Marine Corps’ headquarters in Arlington, Va. He served three tours in Iraq and also took on more political posts, including congressional liaison for the Marines as well as senior aide to Defense Secretaries Robert Gates and Leon Panetta, both of whom worked in multiple White Houses. “This is a guy who is focused on the mission,” Panetta told TIME. “You tell him to take the hill and he will take the hill. Then he’ll tell you there’s a smart way and a dumb way to do it.”

He was sharp and salty, but also collegial and adaptable to any environment. After at least 45 years and 29 moves, he completed his Marine career as head of Southern Command, a four-star post that covers more than countries spanning Central America, South America and the Caribbean. Kelly won wide praise for his work there, but he drew attention when he criticized President Obama’s decision to open combat posts to women and his desire to close the military prison at Guantánamo Bay. Kelly could be famously blunt. Asked about the rise of ISIS in 2016, he said, “As a military guy, it’s simple for me. My part of this equation is to kill as many of them as we can.”

Kelly knows the cost of war too well. His son Robert was killed at age 29 when he stepped on a land mine in Afghanistan, in 2010. Kelly became the highest-ranking U.S. military officer to lose a child in Afghanistan or Iraq since 9/11.

When retirement finally came in 2016, it seemed like a blessing. Kelly took a lucrative job working for DynCorp, a defense contractor, and steered clear of what he described as “the cesspool of domestic politics.” (He also made clear that he was willing to serve for either Hillary Clinton or Trump.) Kelly was watching college football on a Saturday in November when Reince Priebus called to sound him out about a job in the new Administration. Kelly at first thought the call was a prank, the work of some other retired Marines. Once he was convinced it was Priebus, he asked his wife Karen what she thought. Her reply: “If they think they need you, you can’t get out of it. Besides, I’m really tired of this quality retired time we’re spending together.”

Kelly had never met Trump and was surprised when the President-elect offered him the job as Secretary of Homeland Security in the first five minutes of his “interview” at Trump’s Bedminster, N.J., golf resort. The post intrigued him from the start–so did the red flags. Almost immediately, Trump aides tried to install as Kelly’s No. 2 Kansas secretary of state Kris Kobach, whose theories about widespread voter fraud made him a Trump favorite. Kelly resisted and won that battle, but he lost the fight to bring in a deputy of his own choosing. This quickly became the pattern. Aides he wanted on his team were often vetoed by political types around the President. And Kelly, who in his post at Southern Command was responsible for a variety of issues ranging from drug cartels to Latin refugee flows, bristled at the coaching Trump aides tried to give him in advance of his confirmation hearing.

Then came the hastily drafted travel ban. When Kelly first learned of the Executive Order, he asked about White House talking points for the embassies and Congress. The answer: there were none. The incident left Kelly stunned by the Trump team’s lack of preparation. But he appeared before cameras to support the ban and promised to carry it out. That angered Democrats who had backed his nomination. It also endeared him to the President, who found himself defending a travel ban without a workable plan to make it happen.

Trump began to call Kelly, “getting his input, running something by him or saying he was doing a good job,” one West Wing aide recalled. The two men had dinner several times in the first six months, and soon Trump was pressing Kelly to take a larger role at the White House. Kelly resisted, more than once. And yet as his star rose with the President, so did resentment in the West Wing. Former Kelly allies blame jealous White House officials for two notable stories that they feel were designed to damage his relationship with Trump: one alleged that he and Mattis had made a pact that one of them remained stateside all the time, to help preserve stability. The other suggested that Kelly had considered quitting after Trump fired FBI Director James Comey in May. There is some evidence for both reports, but neither is conclusive. True or not, Kelly’s aides considered the stories to be shots across the boss’s bow.

But by mid-July, larger forces were at work. The West Wing was devolving into inexplicable daily chaos, much of it starting with Trump. Priebus never emerged as a chief of staff strong enough to keep the President’s worst instincts at bay. The factional feuding inside the White House among traditional Republicans, family aides and the populists led by Stephen Bannon became an ungovernable embarrassing mess. As threats overseas, particularly from North Korea, loomed larger, Mattis, Tillerson and Dunford pressed Kelly to step in and assert some control for the sake of the country.

Then in late July, when everything seemed to go haywire in the space of a few days–the sudden and disturbing rise of Scaramucci; Trump’s politicized speech to the Boy Scouts at the National Scout Jamboree; the tweet about a transgender ban in the military, which caught Pentagon generals by surprise–Kelly heard from still others out of his past. The refrain: You must do this now. Fred McCorkle, a retired three-star Marine general, explained Kelly this way: “You’ve seen so many people that do this stuff for power. John doesn’t care about power. He’s already had all the power in the world. He’s doing it 100% for service.”

The Kelly effect on White House operations was immediate. He told everyone in the West Wing to report to him and not the President, including, at least in theory, “Javanka,” Washington’s nickname for Kushner and his wife Ivanka Trump. He squelched the flow of unvetted paper to the President, which had sometimes led to erroneous tweets and anecdotes; he listened in on Trump’s conversations with other Cabinet officers. In meetings, he cut off ramblers and told bickering aides to work out their differences before they arrived. Patrolling the West Wing, he told aides to stay in their offices instead of loitering in clumps of five or six outside the Oval Office and trying to catch the President’s eye. (As a result, some White House officials are spending more time on television; it is known to be an excellent way to attract the President’s attention.) And he backed National Security Adviser McMaster, who had been trying for months to remove troublesome allies of Bannon’s without success. Other staff changes are expected. One West Wing aide called the White House under Kelly a “more sane environment.”

Trump has welcomed the change. “Right now, he’s very happy to have someone taking control,” a close aide explains. “I think there will eventually be an adjustment period when he feels like things are working and some others that he wants to revert back or change.”

Which is another way of saying that, in the Trump White House, there are limits to any disciplinarian’s reach. Trump doesn’t take well to constant oversight, and even Republicans worry that any praise heaped on Kelly now could quickly limit, or even end, his influence. And yet if some reports held that Kelly was exerting a moderating force on Trump’s manic tweeting, it was at times hard to tell. Trump was back to his old habits, tweeting from his Bedminster vacation, starting at 6:38 a.m. on Aug. 7 with complaints about “the failing @nytimes” and “24/7 #Fake News on CNN, ABC, NBC, CBS, NYTIMES & WAPO.” By 8:01 a.m., the President had issued nine edicts via social media.

Then on Aug. 8, Trump responded to the latest North Korean threat with some unhelpful, and improvised, language of his own: “North Korea best not make any more threats to the United States. They will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.” The outburst led skeptics–and there are many–to point out Kelly’s influence is overstated. “This was an interesting experiment with General Kelly,” said John Weaver, who is advising Ohio Governor John Kasich, a once and perhaps future rival for the GOP nomination. (One Kelly backer, asked why the new chief of staff didn’t block the “fire and fury” statement, replied only, “You’ll never know how many others he did stop.”)

Meanwhile, it’s far from clear that Kelly (or anyone else) can convert a President with only a passing interest in policy into a legislative force. The extended but failed Republican campaign to repeal Obamacare left the GOP with only 12 legislative days to manage the ritual of raising the debt ceiling by Sept. 29 and passing a budget by Sept. 30. The betting is against them: many GOP lawmakers will likely oppose both measures, which means House Speaker Paul Ryan and Senate leader Mitch McConnell will have to rely on the mercy of Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer to keep the troops paid, the Social Security checks coming and the Treasury borrowing. Failure to do so could plunge the U.S. and global economies into a tailspin. Democrats already know they can practically dictate terms. “Republicans are in the majority,” said one Democratic Senate aide, “but that doesn’t mean they are in charge.”

The GOP is in a bind, which helps explain why the White House is trying to keep the focus on a broad and overdue reform of the tax code. Tax simplification (and the promise of lower rates for some) is far more popular with voters and lawmakers than passing spending bills, but it is probably impossible to execute this year, at least in this environment. Under the best-case scenario, it may be years away: the last time Congress went down that road, in the quaintly bipartisan mid-1980s, it took three years to pull off from start to finish.

And there are a host of other headaches for the new chief of staff to manage. The President’s poll ratings continue to drift downward, which leads Trump to tweet and speak disproportionately to his base if only to keep it propped up. The Russia probe appears to be gathering speed as special counsel Robert Mueller works with an active grand jury and examines the relationship that Trump’s first National Security Adviser, retired general Michael Flynn, had with Moscow and the government of Turkey. (The Washington Post reported on Aug. 9 that FBI agents working under Mueller raided the home of former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort on July 26.) The generals seem unified in their desire to persuade Trump to put more U.S. forces in Afghanistan, despite the opposition of populists led by Bannon. And then there is the still unresolved question of whether Trump will carry out his promised ban on transgender service members.

Trump gets bored with people easily and has a history of blaming aides for his own missteps. Even Kelly may not be immune. One former aide who has fallen from grace suggested it was only a matter of time. But Kelly is clear-eyed about the mission: it is not so much about “fixing” Trump as it is earning the President’s trust so that he can make repairs to White House operations quickly, before an international incident tests the team.

But it is also likely that Trump knows on some level that his presidency and perhaps the nation hang in the balance. In moments of crisis, American political leaders have often turned to the nation’s military brass to guide the country with clear thinking. For the time being, current and former officers are positioned to perform double duty, providing for the common defense abroad and a measure of common sense at home. If that isn’t what the Founders had in mind when they drafted the Constitution, it is also preferable to several other possibilities that could still become reality. The arrangement bears close watching. But in the case of John Kelly, it is a reminder of what a lifetime of service to the nation can mean.

–With reporting by ALEX ALTMAN, MASSIMO CALABRESI, PHILIP ELLIOTT, ZEKE J. MILLER and MAYA RHODAN/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com