In Tunisia, change came gradually and then suddenly. When a police officer confiscated the goods of an unlicensed vegetable seller in December 2010, the merchant drenched himself in gasoline and set himself alight. During the 18 days it took Mohammed Bouazizi to die, his story spread across the Arab world. Public anger grew, and protests swelled. On Jan. 4, 2011, Bouazizi died. Ten days later, the 23-year dictatorship of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali was brought to its knees. The Arab Spring advanced to Egypt and Libya, toppling and threatening autocrats across the region.

The aftershocks continue six and a half years later. Libya remains divided, Syria is mired in civil war, and the Egyptian and Saudi governments have taken a hard line on political Islam. Tunisia, meanwhile, has become the Arab world’s one true free-market democracy. Crucially, its revolution didn’t end with a factional war. Many political movements were included in the country’s new national unity government. International donors stepped in to help. Tunisian democracy activists won a Nobel Peace Prize.

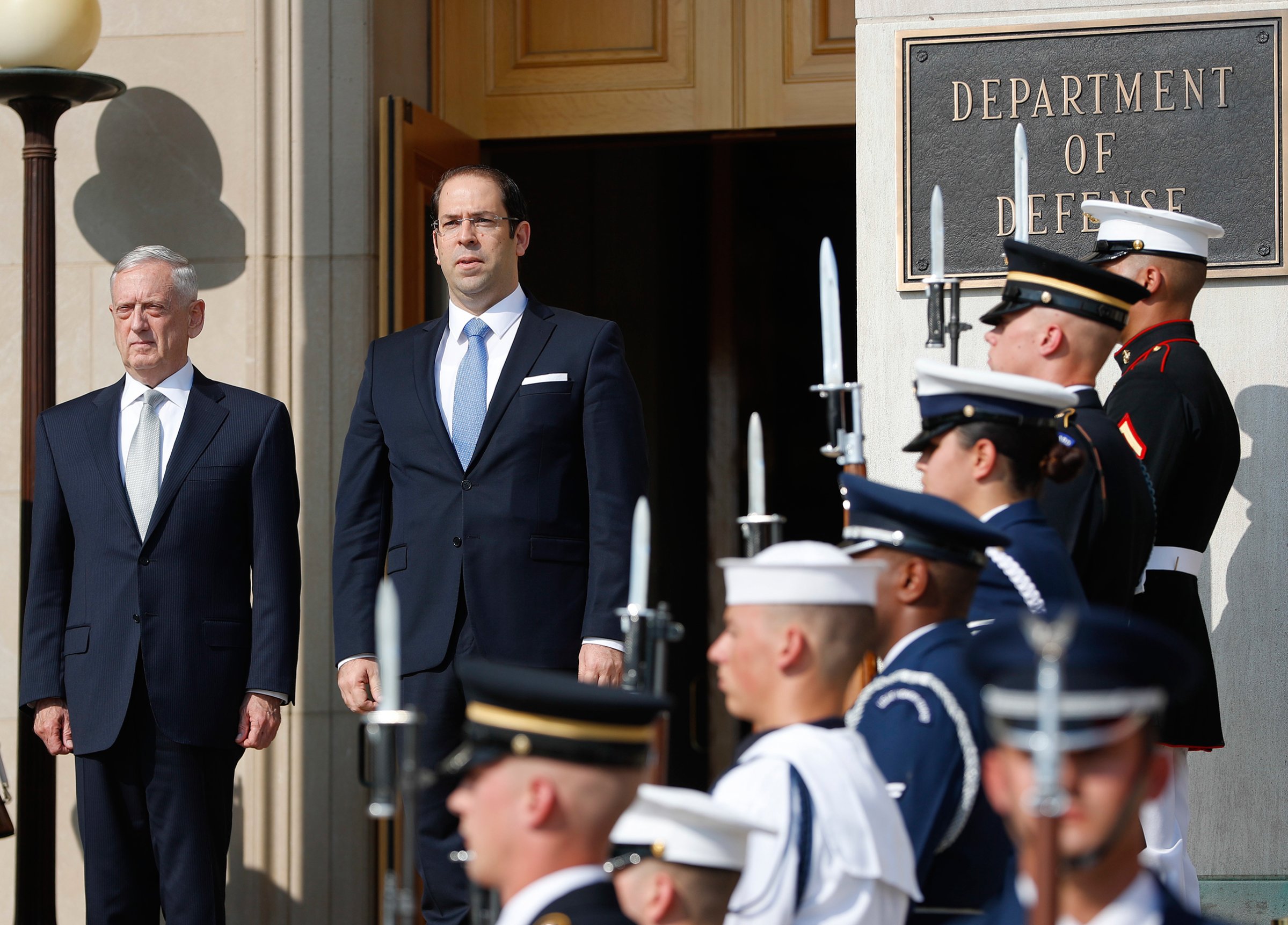

Now, things are getting tougher. A series of high-profile terrorist attacks have hurt tourism, an important part of Tunisia’s economy, and growth has stalled. Lack of faith in the future has created a grim trend: a number of Tunisians have followed Bouazizi’s example and set themselves on fire, a bitter legacy for the Arab Spring’s most compelling success story. Given all this, can Tunisia remain an outpost of stability and an ally against Islamist militants? That’s the main question I had for Prime Minister Youssef Chahed when we met in Washington on July 10.

The former minister of local affairs, just 41, was appointed a year ago after his predecessor, Habib Essid, was ousted partly for his failure to manage the economy. Slow growth is still a key part of Tunisia’s story. Before the uprising, its economic growth was on track to reach 5.4% in 2011. Today, it’s around 1%. “We spent five years trying to build democratic institutions, and we succeeded in that,” he said. “Our high level of unemployment, at about 15%, is the challenge now.”

Another challenge at least as pressing is the country’s security situation. Since a trio of major attacks in 2015, Tunisia has been under a state of emergency, and Chahed says its unstable ISIS-infected next-door neighbor has made matters worse. “We have 500 km of border with Libya … [my government’s] principal priority is the war against terrorism and the situation in Libya.”

Yet it’s difficult to see how Tunisia will tackle either of these without continued financial assistance from the U.S. and other major powers–and the country got a nasty shock when President Donald Trump’s proposed budget slashed bilateral aid to Tunisia by 67%. Chahed was in Washington to try to persuade the White House that his country remains an ally worthy of U.S. support. “I tried to explain to our friends in the U.S. that Tunisia is really at the front line of the fight against terrorism, the fight against ISIS … We have realized concrete gains against those groups, and any discontinuation [of support] at this moment will send the wrong message to terrorists,” Chahed said. If the Trump Administration won’t support Tunisia’s democracy, he suggests, maybe it will recognize the country’s value as a natural regional ally against ISIS and al-Qaeda.

The need for backing has taken on new urgency. Qatar, a crucial financial supporter, finds itself isolated by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt. The IMF has been a patient backer of Tunisia, but unless deficits are brought under control, the Fund may begin to fear it’s throwing good money after bad. Traditional ally France has so far done little to help its former colonial outpost, although maybe President Emmanuel Macron will offer more. Tunisia’s achievements should not be overlooked by the world, Chahed says. “We had a fair and free election in 2014,” he says. “Political parties, freedom of speech, freedom of religion and freedom of economic initiative. All of this exists in Tunisia now.”

In the end, however, it may be the neighbors who matter most. “Qatar, Saudi Arabia, we have very good relations with both and all those countries,” Chahed says. Tunisia’s neutrality allows it to play the role of peacemaker and protects it from fallout from the fights of other governments, he explains. But you wonder just how sorry the autocrats of the Arab world would be if the region’s most promising democracy were to fall on hard times.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com