Last month, the Congressional Budget Office released its evaluation of the House of Representative’s American Health Care Act. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the AHCA would, if it becomes law, leave 23 million more Americans uninsured by the end of the decade. While the Senate’s newly unveiled bill will receive similar scrutiny in the coming days, much has rightly been made of this figure and the consequences of so many losing vital coverage. Proponents have framed the legislation as a chance for Americans to take personal responsibility for their health, while opponents have decried its potential to sicken and kill many of our most vulnerable citizens. These concerns are valid. The bill stands to do great harm.

In the midst of this debate, with so many slogans and statistics in the air, it is important to discuss not just the harm that will come from lack of coverage, but the reasons why so many Americans are sick in the first place. Repealing the current health care law — the Affordable Care Act — would be catastrophic precisely because the need for such a law is so great. Responding to this need is not just a matter of politics, it is a question of justice.

A story, to explain why.

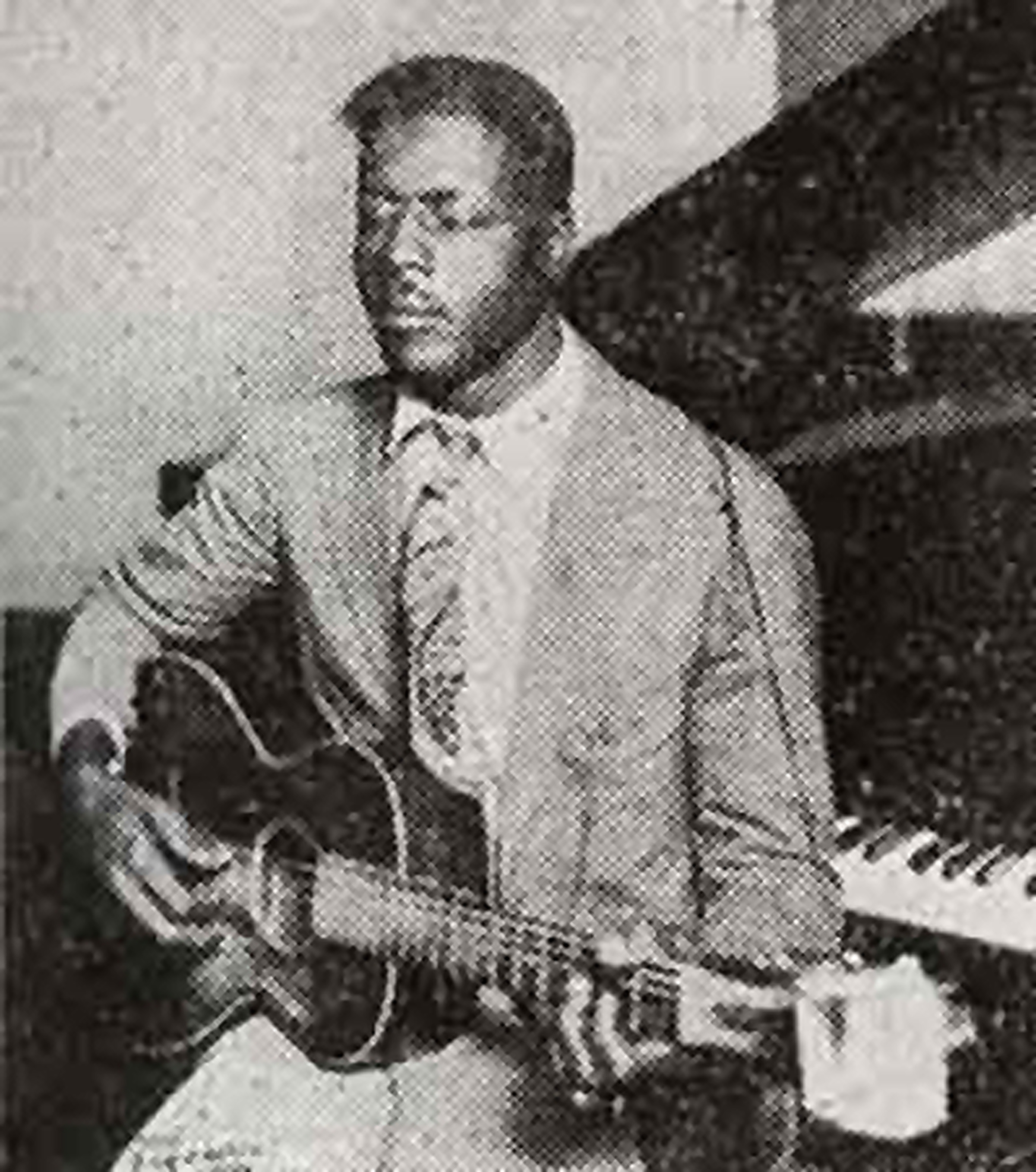

In 1977, the Voyager 1 spacecraft lifted off into the cosmos. The craft’s mission, which remains ongoing, is to explore the universe, to “boldly go” where no human-made object has gone before. In case Voyager 1 is ever encountered by curious extraterrestrials, it carries a golden record imprinted with a range of carefully-selected recordings. They include bird calls, a human heartbeat, the sound of waves breaking against the shore, and a number of musical selections. Among these recordings is a song called “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” by the blues singer Blind Willie Johnson. The song was selected by the astrophysicist Carl Sagan, who thought it reflected the familiar human experience of “nightfall with no place to sleep.”

No one is sure what the song is about. It has no lyrics. It is composed of moans, of raw feeling. Some say it is about the crucifixion of Christ. Suffering is its clear theme, though whether or not Johnson saw suffering as redemptive is a question only he could have answered. Certainly he knew hardship. Born in 1897, in Texas, the story goes that, when Johnson was young, his stepmother threw lye in his face out of spite for his father’s infidelity. Blind and penniless, Johnson played and preached on the streets to earn a living. In 1945, his house burned down. With nowhere to go, he lived in the ruins, sleeping on a damp bed until he caught malaria and died. His wife said she tried to take him to a hospital but he was refused treatment, either because he was blind or because he was black.

I tell this story because it is the story of health in the United States, as far too many Americans still experience it. On the surface, Johnson’s life may seem like the tragedy of an individual. It is not. His fate was determined by powerful social, economic and environmental forces that, taken together, shape the wellbeing of populations at the structural level. For example, the brutality of Johnson’s upbringing was no outlier. Black children in America are far likelier to witness violence than white children. And while he may have succumbed to malaria, his true killer was poverty, a poverty which remains acute in the US. We also know the data behind racial disparities in health care. While doctors can no longer legally turn patients away because of race, pernicious gaps in treatment continue to undermine the health of black populations.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” is the product of a life shaped by injustice. Racism, abuse, lack of medical care, racism again; these are the factors that determined Johnson’s health. Nearly a century after he recorded his song, his reality remains true for millions of Americans born in a certain place, in a certain skin, under certain economic and social conditions that we as a people still have not fully addressed.

Unfortunately, our national conversation about health in general, and health care in particular, rarely acknowledges how injustice shapes the health of populations. In the U.S., when we talk about health, we tend to focus on the medicines we take, doctor’s visits, the amount of exercise we manage to squeeze in — in short, our individual behavior. It is not hard to see why we would think this way. With our collective emphasis on lifestyle as the primary driver of health, we are, in a sense, culturally conditioned to view poor health as a consequence of poor decision-making. It takes little imagination to assume that someone is obese because she has made a choice to eat too much. It takes more effort to consider how her obesity represents the convergence of many contextual factors over which she has little or no control. In reality, obesity is caused by the same injustice that inspired “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.” It is caused by poverty. Junk food is cheap, and poor neighborhoods frequently lack high-quality markets that carry a nutritious selection of ingredients. We can reduce obesity by reducing poverty, as well as through policy solutions like taxing sugary drinks.

Am I saying that in order to have healthy populations, we must somehow cure racism and poverty? That we must change our society at the structural level, shifting entrenched norms, often in the face of powerful political resistance?

Yes, I am.

Say that Blind Willie Johnson had received treatment for his malaria, the best money could buy. He still would have had to return to the same bed of ashes, the same destitute conditions that made him vulnerable to disease in the first place. A society that condemns people to such a fate is not a healthy society. Even if overall wellbeing improves, as long as marginalized groups remain disproportionately at risk of preventable hazards, we have failed to meet our obligations to one another. To truly make a difference, the cause of justice must become the cause of health.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com