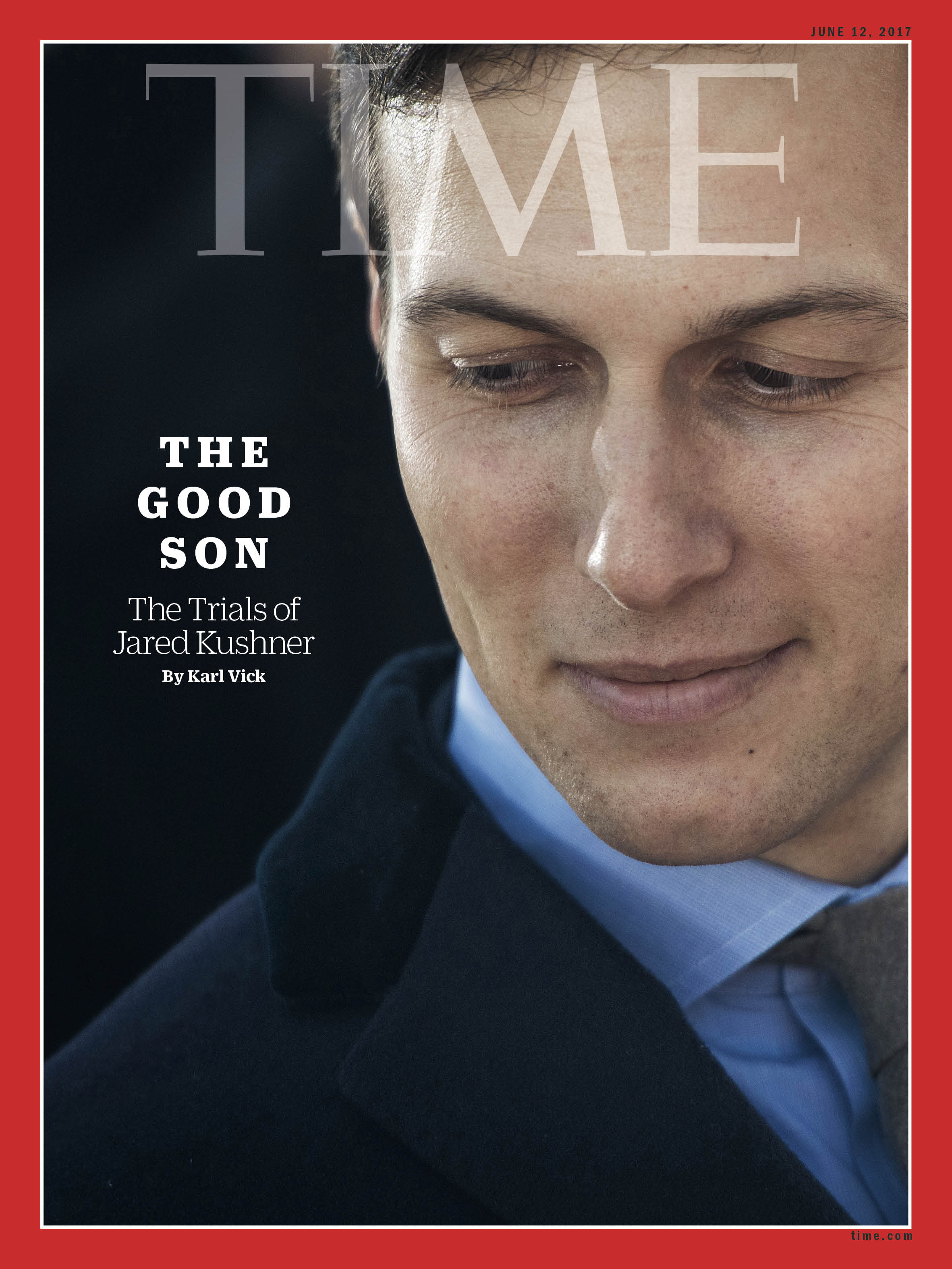

If one thing emerged crystal clear from the muddy first months of his father-in-law’s presidency, it’s that Jared Kushner prefers the background.

That’s where the camera found him in pretty much every official setting–among the flags and the rhododendron, stock still and strangely unchanged from one photo to another: spread collar, thin tie and dimpled, inscrutable smile. The senior adviser to the President was also the cipher of the White House–never heard in public, a blank page on which an anxious public could write its hopes. To moderates, he was the son of a prominent Democratic family, relied upon to be, with his wife Ivanka Trump, a calming voice of reason in the ear of a churlish, impetuous President. Donald Trump loyalists understood him as the most loyal of all, guided by the two words that both men repeat: “Family first.”

It’s a situation that might have survived had Kushner remained in the dog-eat-dog world of Manhattan real estate, where behind every empire builder with his name on a building lurks a discreet dealmaker and consigliere, scouring fine print, quietly finding opportunity and making problems disappear. But Washington is a town of rank and title, where secrets are hard to keep, official roles matter and the higher power of the Constitution looms. The quiet man is now conspicuous, having been slurped into the spotlight by the tentacles of a Russia investigation that produces headlines like Ford punches out trucks.

Just before Memorial Day weekend, news broke that Russia’s ambassador to the U.S., Sergey Kislyak, told the Kremlin last December that Kushner wanted to open a private communications channel with Moscow, perhaps even using Russia’s secret communications equipment to do it. The notion reportedly startled even Kislyak and bewildered the U.S. intelligence services that had intercepted his message. Kushner’s defenders acknowledged that the meeting took place but suggested that talk of a secret channel might be Russian disinformation. But once the story broke that investigators were actively looking into Kushner’s undisclosed contacts with Russians, the shadow of the FBI probe spread to the White House itself for the first time.

Just as concerning for investigators was Kushner’s meeting with Sergey Gorkov, the head of Russia’s Vnesheconombank, later in the same month at the request of Kislyak. The bank is closely tied to the leadership of the Russian government and has been enmeshed in the activities of its intelligence services. One employee in its New York office, Evgeny Buryakov, was arrested in 2015 for espionage after he was caught collecting intelligence on Wall Street’s high-tech financial systems. One of Buryakov’s handlers had tried to recruit Carter Page, who was a foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign. Buryakov was sentenced to 30 months in prison in 2016 and deported earlier this year.

There is no indication that Kushner is a target of the Russia probe, officials say, and he has not publicly commented on either meeting, though his attorneys say he is happy to speak with investigators at an appropriate time. The bar to prove that someone improperly colluded with a foreign power is very high, and even the most aggressive investigators use a note of caution when speaking of Kushner’s role in the probe. “He’s an ends-justifies-the-means guy,” says one U.S. official familiar with the investigation. “It could be naiveté, but the investigation is about finding that out.”

Naiveté is no crime, but Washington’s punishment of perceived incompetence can be swift and brutal. The political frenzy around the back-channel meeting–with some Democrats calling for the suspension of Kushner’s security clearance–has left no visible dent in Kushner’s supreme self-confidence. That has created its own problems. Among Trump’s senior-most advisers, Kushner, 36, was quick to support his decision to fire of FBI Director James Comey, the official in charge of the Russia probe.

The ensuing, entirely predictable uproar resulted in the appointment of a special counsel, who will keep the probe alive for months. It also alienated the FBI rank and file. “[Trump] pissed off the building,” says a former U.S. official familiar with the investigation. “Now they’re doubling down twice as hard” on the probe.

The immediate political consequence is uncomfortable; it brings the investigation as close to the President as Kushner, which is as close as things get in the White House. In the Venn diagram that describes operations in the West Wing, only Jared and Ivanka, who has an office upstairs, occupy the overlapping zone of government servant and family. And even in that exclusive subset, Kushner occupies a place all his own, having already performed service as discreet agent and protector during the presidential campaign, and before.

The setting is new, but Kushner has been tested by public scandal before, by intense prosecutorial heat and by the fraught blending of family business and politics that now defines the Trump brand. He became an adult as a defender of his family name after his father was convicted and sent to prison after attempting to smear the reputation of his own brother-in-law. In that drama, too, the younger Kushner saw himself as calm and quick-thinking, able to mostly separate his talents for problem solving from the limits of what he did not yet know. It’s the role he played in his business success and even in the Trump presidential campaign, which supporters described as a “movement” but Kushner understood as both an extraordinary opportunity and as a problem to solve.

“Knowing him, I don’t even think he could consider the politics of it, party-wise,” explains Asher Abehsera, Kushner’s partner in several real estate projects. “I think he’s like, ‘Here I am, he’s my father-in-law, and I could do this and this and this and it could help him.’ And he did this and this and this, and it helped him. And that mushroomed into today.”

It was lost on no one in Washington that Kushner landed perhaps the best office in the West Wing, a space that abuts the President’s private dining room, just steps from the Oval Office. The room was previously used by President Obama’s top strategists, first David Axelrod and then David Plouffe, who filled it with political memorabilia, maps, bookcases, sometimes photos of themselves at key moments in life. Kushner has so far treated the space as a waiting room, with bare white walls, save a television, a whiteboard and a gold-rimmed mirror.

Instead of placing comfortable chairs for visitors before his desk, he has stuck his workspace against a wall. That has made way for a conference table for regular meetings with the growing team of aides who report to him. His brief is both enormous and selective, allowing him to leave on family vacations in the first months in office with minimal disruption. Among the projects he has had a hand in are a host of foreign deals, including a recent $110 billion weapons sale to Saudi Arabia; diplomatic outreach to Mexico, Canada, China and Israel; and government reinvention efforts focused on Veterans Affairs, information-technology contracting and the opioid crisis. People who report to him like to joke that they travel below the waves, away from the daily outrages that now consume the news cycle, trying to keep on task, find the next deal. Kushner will also occasionally meet here with journalists, though he stays in the deep, not speaking for the record. He declined to comment for this story.

Even before he found himself, at age 36, as a senior counselor to the President, Jared Kushner’s life had the epic sweep and the dramatic reversals of a 19th century novel. There was a childhood in suburban Livingston, N.J., an Orthodox Jewish upbringing in a home that suggested little of the family’s wealth, four years at Harvard, then studies in law and business. But the story really began the summer day in 2004 that the protagonist, at 23, learned his father had been arrested after trying to bring down his own family.

His father Charles Kushner was the son of Holocaust survivors, who arrived in America after World War II. The grandfather worked as a carpenter, then began building houses in New Jersey. When Charles took over the business, he carried the second-generation immigrant story into rarified territory. His firstborn son spent his formative years watching his friends go off to summer camps or football games while he tagged along with his father to construction sites or to see new prospective properties on Sundays.

Before long, Kushner Companies owned 20,000 homes, generating wealth that Charles made a point of spreading around. “It got to be embarrassing to call him,” says Arthur Mirante II, a business associate and friend whom Kushner tapped for a contribution to the yeshiva he started to honor his father. After they became friends, he would brace himself when he called for a cause of his own: “I’d ask for $10,000, he’d give $300,000.”

Charles Kushner also contributed to politicians. It’s what real estate developers do, but Kushner’s amounts demonstrated an appetite for more than approval of building projects or favorite causes like Israel. (Benjamin Netanyahu once spent the night at the Livingston home.) Kushner made himself a major player in New Jersey Democratic politics. He was the primary backer of a governor, Jim McGreevey, who nominated him for chairman of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in 2003, just as Kushner’s world began to unravel.

Federal law limits how much an individual can contribute to a candidate, but like many big givers, Kushner skirted the letter of the law by sending money in the name of assorted family members. The problem was an ugly rift in the extended Kushner clan. Those arrayed against Charles lined up with investigators. Charles responded by arranging for his brother-in-law to be videotaped with a prostitute, then mailed the tape to the man’s wife–which is to say, his own sister.

The plan backfired. Charles’ sister took the tape to the feds, and Charles was convicted of 18 felony counts, including witness tampering. The prosecution of the prominent Democrat was led by the U.S. attorney for New Jersey at the time, Chris Christie, who at sentencing called him “downright evil.” Christie went on to become the governor of New Jersey. Charles went on to serve about half of a two-year sentence, in Montgomery, Ala. Jared flew down to visit him nearly every weekend.

Investigators in the Russia probe may well consider how the searing experience with the U.S. attorney’s office may have colored Jared’s attitude toward the law. At the time of his father’s arrest, he was interning at the office of the New York prosecutor Robert Morgenthau. He set aside any thoughts of a career in law and, when asked years later about his father’s transgression, argued that he was more sinned against than a sinner. And that the greatest sin was going against family.

“His siblings stole every piece of paper from his office, and they took it to the government,” Jared told New York magazine in 2009. “He gave them interests in the business for nothing. All he did was put the tape together and send it. Was it the right thing to do? At the end of the day, it was a function of saying, ‘You’re trying to make my life miserable? Well, I’m doing the same.'”

What followed was a loyal son’s methodical, strikingly successful campaign of restoration and self-creation, one that happened to track the success story of his future father-in-law, moving to New York to make it big in real estate. The quest began with a purchase that had everything to do with social status. The New York Observer was a weekly newspaper on salmon newsprint with a tiny circulation. But it was read by a Manhattan elite that liked its blend of gossip and intrigue. Kushner bought it for $10 million in cash, stepping in front of a bid that included Robert De Niro’s Tribeca Enterprises, to announce his arrival in Manhattan, at age 25.

“His graduation present was the Observer,” says Mirante. It was not Charles Kushner’s first conspicuous investment in his eldest son. In 1998, the father pledged $2.5 million to Harvard, a contribution featured in Daniel Golden’s The Price of Admission, which quoted a counselor at Jared’s prep school as saying his grades and test scores would not themselves justify admission to Harvard, where he was nonetheless admitted.

Family first: Jared assumed leadership of Kushner Companies, since establishment banks would not lend to a convicted felon. But Charles, after his 2006 release, worked down the hall and was both a participant and a beneficiary of the course the company now set: unloading its New Jersey holdings and crossing the Hudson to make its mark in New York City.

The family planted its flag at 666 Fifth Avenue, paying $1.8 billion for a 41-story aluminum-clad tower, a record amount for an office building at the time–which unfortunately was 2007, the peak of the real estate bubble. The company only just navigated the downturn, selling a 49% share, but then, undaunted, looked around for more: its trophies include the Puck Building, where Jared and Ivanka own, and a swath of Brooklyn Heights previously held by the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ world headquarters. As Kushner Companies grew from 70 employees to 700, the prominence of Charles’ conviction shrank. Friends say that was the idea.

“I think that Jared got into the real estate business and pursued some very marquee transactions as a way to redeem the family’s name,” says Sandeep Mathrani, a prominent developer who advised Jared when “his father was not in a good place.”

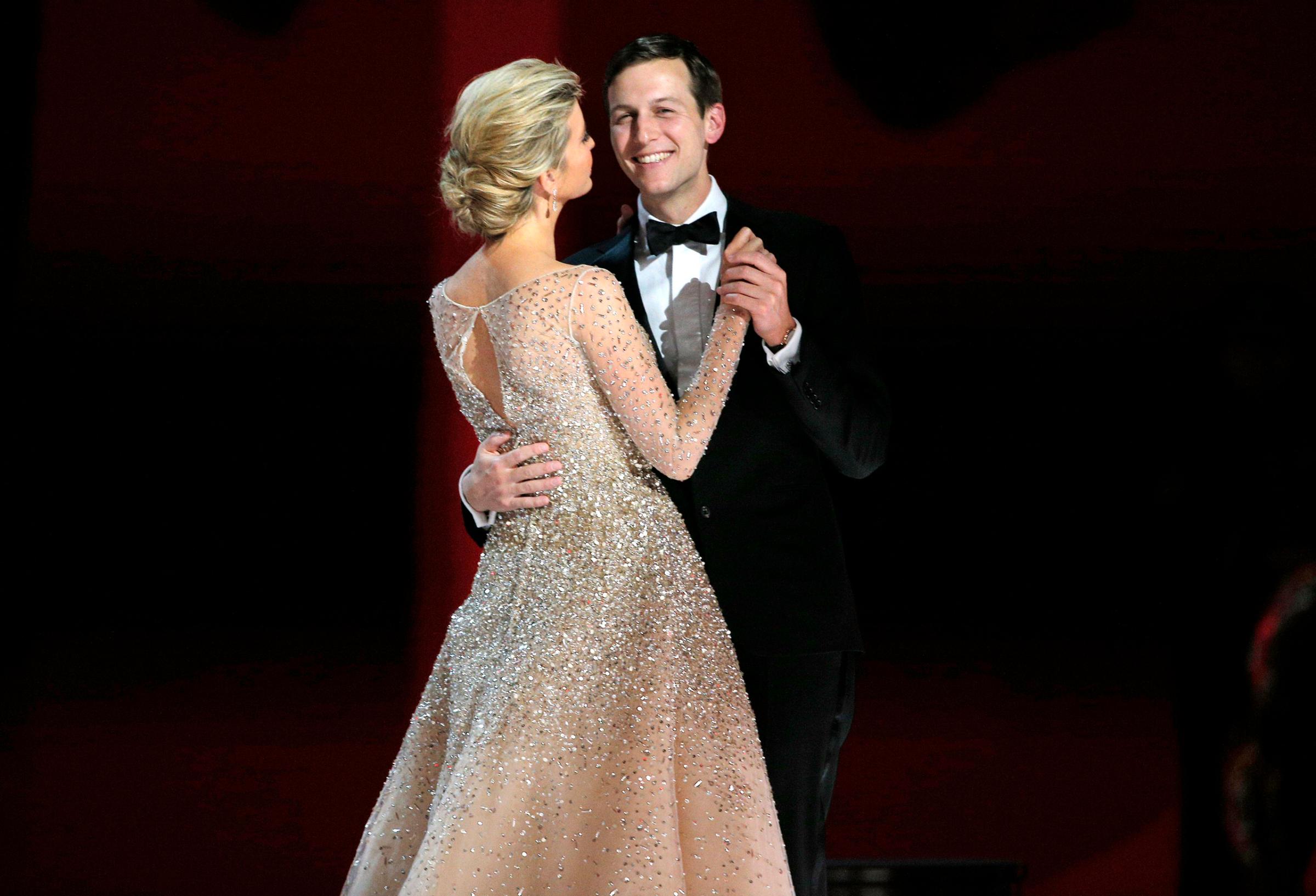

Along the way, the Kushners became certified New Yorkers. His parents moved to the Upper East Side. Jared made himself at home in establishment circles like the Partnership for New York City, started a real estate version of the Observer with its own Power 100 awards dinner and, at a business lunch in 2007, met Ivanka.

From a distance, their union could be mistaken for a political marriage–a merger of two family empires. But it was not universally desired. There were breakups. Kushner’s parents wanted their son to marry within the faith. Privately, friends also mention eye-rolling at the prospect of being related to Donald Trump, whose preoccupation was not with the New York Observer but the tabloids (which dubbed the pair J-Vanka). But the young couple persisted.

Their reunion was arranged on a yacht of Wendi Deng’s, then wife of Rupert Murdoch. After Ivanka removed the Kushners’ only stated objection by converting to Judaism–studying at the Upper East Side synagogue Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun–the wedding was held in Bedminster, N.J., at the Trump National Golf Club.

Until he ran for President, Trump was not someone who depended on his son-in-law. Ivanka, Jared and the kids–now ages 5, 3 and 1–would travel to Mar-a-Lago for Thanksgiving, and the young family had a summer house next to Trump’s in Bedminster. But Kushner was immersed in business, including the real estate investing platform Cadre, with billionaire Peter Thiel and others, including his brother Josh, who was better known for his role in Oscar, a health-insurance company tailored to Obamacare, and for his relationship with supermodel Karlie Kloss. Almost everyone in the family was a Democrat.

See Jared Kushner's Life in Pictures

But when Trump announced his candidacy for President in June 2015, Jared made himself available, at first out of familial duty. That changed on Nov. 9, 2015, in Springfield, Ill., at a Trump rally, Kushner’s first. The candidate entered to the music of Twisted Sister: “We’re not going to take it.” The crowd of 10,200 was the largest ever gathered in the convention center and went wild for the candidate whom the political establishment regarded as a joke. Kushner had grown up bantering about politics; he’d bought a website devoted to the minutia of Jersey politics. But this was something else. This was primal.

As Kushner has told it, the young scion glimpsed a world outside his own Upper East Side bubble, a country roiled by grievance and frustration, looking for the champion Trump was eager to become. The data-focused real estate magnate returned to New York convinced that his father-in law would be the Republican nominee. In the months that followed, he steadily took on more tasks in the campaign. He found policy advisers who could write issue white papers–at least once anonymously, given the notoriety of the candidate, and for twice the regular fee. He scrambled to write speeches on topics wholly new to him, leaned heavily on senior aide Stephen Miller and–a point of particular pride–reinvented Trump’s threadbare online advertising and fundraising operation. Using Facebook as his data bank, he helped turn the Make America Great Again hat from a curiosity into a fashion trend, direct targeting ads online that brought in as much as $80,000 a day. “Jared Kushner’s a rock star,” Brad Parscale, who ran Trump’s digital operation, told TIME last year. “He’s a mad scientist.”

In time, it would became apparent that the campaign was not the only operation microtargeting Trump supporters through Facebook. Federal investigators later learned that Russian operatives were doing the same thing and are looking at whether the two camps cooperated with each other. Investigators are not certain of what to make of Kushner’s contacts with the Russians; he didn’t disclose them or any other foreign contacts when he initially applied for top-secret security clearance. Over the course of the campaign, Reuters reported, Kushner had two undisclosed phone conversations with Russian ambassador Kislyak and one other contact. (Kushner’s lawyers say he participated in “thousands of calls” and corrected his security-clearance application on his own initiative.)

There have been other headaches. Jared’s responsibilities include policy toward China, which first proved awkward when Kushner Companies courted the Anbang Insurance Group, a Chinese company linked to the Beijing leadership, as an investor at 666 Fifth Avenue. The company has since backed away, but in May one of Kushner’s sisters went to China in search of investors for another project, in Jersey City, trading on the family name in road-show presentations and dangling U.S. visas. The company apologized, and Kushner argues that everyone is adjusting to life as public servants: neither he nor Ivanka (who has had her own embarrassing business conflicts) structured their lives, or their complex finances, with a political career in mind.

Inside the White House, the promise of Kushner and his wife playing a moderating force may be overblown. They are more politically liberal than most but view themselves primarily as Trump’s protectors, even though their counsel can fall out of favor with the President at times. It’s with that last goal in mind that they have pushed Trump to temper his rhetoric on NATO and the Muslim world, and argued that he should remain in the Paris climate accords. In the White House, Kushner’s ability to skirt the system has made him popular among the town’s diplomatic corps but has led to strains inside the building, which has yet to find a coherent organization. Whether it was wise to entrust such a vast and complicated portfolio to a policy novice is one of the questions that will define Trump’s first term.

As with everyone else in the West Wing, the relationship that matters most is with the boss. They both earned their stripes the same way, in Manhattan media and real estate. They both see the world through the lens of deals, surmising their own best talent as being able to come out of any new situation a winner. Their best stories tend to carry the same moral: that they outsmarted, outhustled or outperformed everyone else around.

As a result, Kushner has the liberty to work on long-term projects because, unlike those around him, he does not have to worry about his job. His bond with the President, like that of his wife, is more elemental, even if they find themselves in occasional disagreement. For this reason, despite the swirl around him, Kushner has been projecting a level of calm. There have been crises before, even prosecutors. He likes to believe that he knows how to distinguish the real threats from the bogus ones, the dangers from the risks worth taking.

What neither man knows is whether the lessons of New York blood sport can be translated to Washington. For both men, the challenge of running a nation and steering the world is entirely new. They share the same wager that relationships and instinct can substitute for experience. And despite the wealth and validation that they’ve accumulated, both have identified as outsiders. Now, with adjacent windows overlooking the White House lawn, they are bound to rise or fall together.

–With reporting by PHILIP ELLIOTT, MASSIMO CALABRESI, ZEKE J. MILLER and MICHAEL SCHERER/WASHINGTON

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described Kushner’s role in the firing of FBI director James Comey. He supported the firing, but did not urge it, according to sources familiar with the situation.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com