Milestone moments do not a year make. Often, it’s the smaller news stories that add up, gradually, to big history. With that in mind, in 2017 TIME History will revisit the entire year of 1967, week by week, as it was reported in the pages of TIME. Catch up on last week’s installment here.

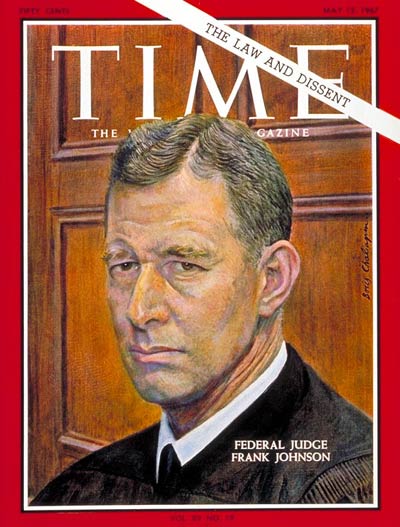

President Lyndon Johnson and the Supreme Court tend to get the most credit for the political advances of the civil rights era, but this week’s cover story introduces readers to a lesser-known figure who played a critical role: Frank Minis Johnson, a U.S. district judge who had served for more than a decade in southeastern Alabama. His interpretations of the law, the story explained, were why the state was making what progress it was on the enforcement of civil rights law:

It was Frank Johnson who applied the school-desegregation decision to the Montgomery bus system — and thus helped speed desegregation of all public facilities in the South. It was Frank Johnson who ordered both marchers and police to halt their confrontation at Selma, and then — although he disapproves of most demonstrations — gave the marchers permission to go ahead.

It was Frank Johnson who sat as a member of the three-judge court that abolished the Alabama poll tax; that handed down the first order requiring a state to reapportion its devised by judges. It was Frank who so inspired an Alabama with a sense of responsibility that it was able to convict the three Ku Klux Klansmen who gunned down Viola Liuzzo on the road back to Montgomery from Selma. It was Frank Johnson who mustered the three-judge court that has just ordered desegregation of all of Alabama’s 118 school districts next fall — the first such statewide ruling in the nation, and perhaps the most important school order since the Supreme Court’s school decision of 1954.

As the story noted, dozens of his colleagues in the South had chosen to go a different route, choosing not to interpret laws that were locally unpopular in such a way that would make waves. Johnson (who had gone to law school with George Wallace, the segregationist Alabama governor who was preparing to run a third-party campaign for the White House) believed, however, that it was the job of a judge in his position not to advocate for any political position but rather to apply the facts of the law to whatever the case happened to be. As integration was the law, he would enforce it no matter what the local preference might be.

As a result, Johnson, as one anonymous source told the magazine, “gives ’em all hell.”

Affirmative Action: This letter from a reader reminded me of the conversation about last year’s Supreme Court ruling on affirmative action at the University of Texas, which held that the way the university considered race in admissions decisions was legal, after the plaintiff argued that being white had caused her to be rejected from the college. The reader, reacting to a piece about newly integrated colleges competing to attract black students, quips that her daughter — ranked 25th in her class and with good test scores — had been waitlisted at two Ivy League schools so she would have plenty of fodder for a book about how being white had disadvantaged her.

Protest Protest: Another parallel to modern news can be found in the magazine’s coverage of what happened when George Wallace was invited to speak at Dartmouth College. A group of about 50 students prevented him from speaking and then mobbed his car. TIME took a clear position on the issue as a violation of his “right to be heard and that of others to listen” — but Wallace himself clearly saw it as a prime opportunity to get even more national attention for his views, including his position that academic freedom “can get you killed.”

Out of this World: Here’s Barron Hilton, of the Hilton hotel chain, describing “his plans for the Lunar Hilton, an underground 100-room hotel to be built just below the moon’s crust.”

Secret Advocacy: Columbia, the education section reported, had become the first college in the U.S. to be home to a club supporting LGBT rights. The only problem with the group: though the student body was apparently open enough to the idea of such a club, it was not open enough for the members to feel comfortable saying who they were. “The league’s biggest problem will probably be its self-imposed secrecy,” the magazine noted. “As some students asked: How do you treat them equally when you don’t know who they are?”

Cutting Edge: Meet the sports world’s latest innovation — Astroturf. About a year after the Houston Astros first installed the artificial turf in their Astrodome (“as a last-minute solution after the lack of direct sun light killed the natural grass,” TIME explained) more than a dozen manufacturers were turning out some version of the hit product.

In the Shade: A story about a doctor’s campaign to discourage tanning, which he explained led to skin cancer, offered TIME a chance to examine the shift in social norms that had made tanning an issue for 1960s readers. Through the 19th century, the magazine noted, “colonialist snobbery” had been part of the reason why many white people avoided sun exposure that would make their skin darker. In the 1920s, however, some public health advocates pushed the idea that the sun-induced production of Vitamin D might help control tuberculosis, and a suntan became a symbol of good health for many Americans who didn’t yet know that it was actually harmful. (One thing the science in the ’60s got wrong still: it is incorrect that people with darker skin are naturally protected from skin cancer.)

Great vintage ad: This is, surprisingly, an ad for packaging rather than an ad for stockings — but I just love the ’60s fashion on display in the design.

Coming up next week: Johnny Carson

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com