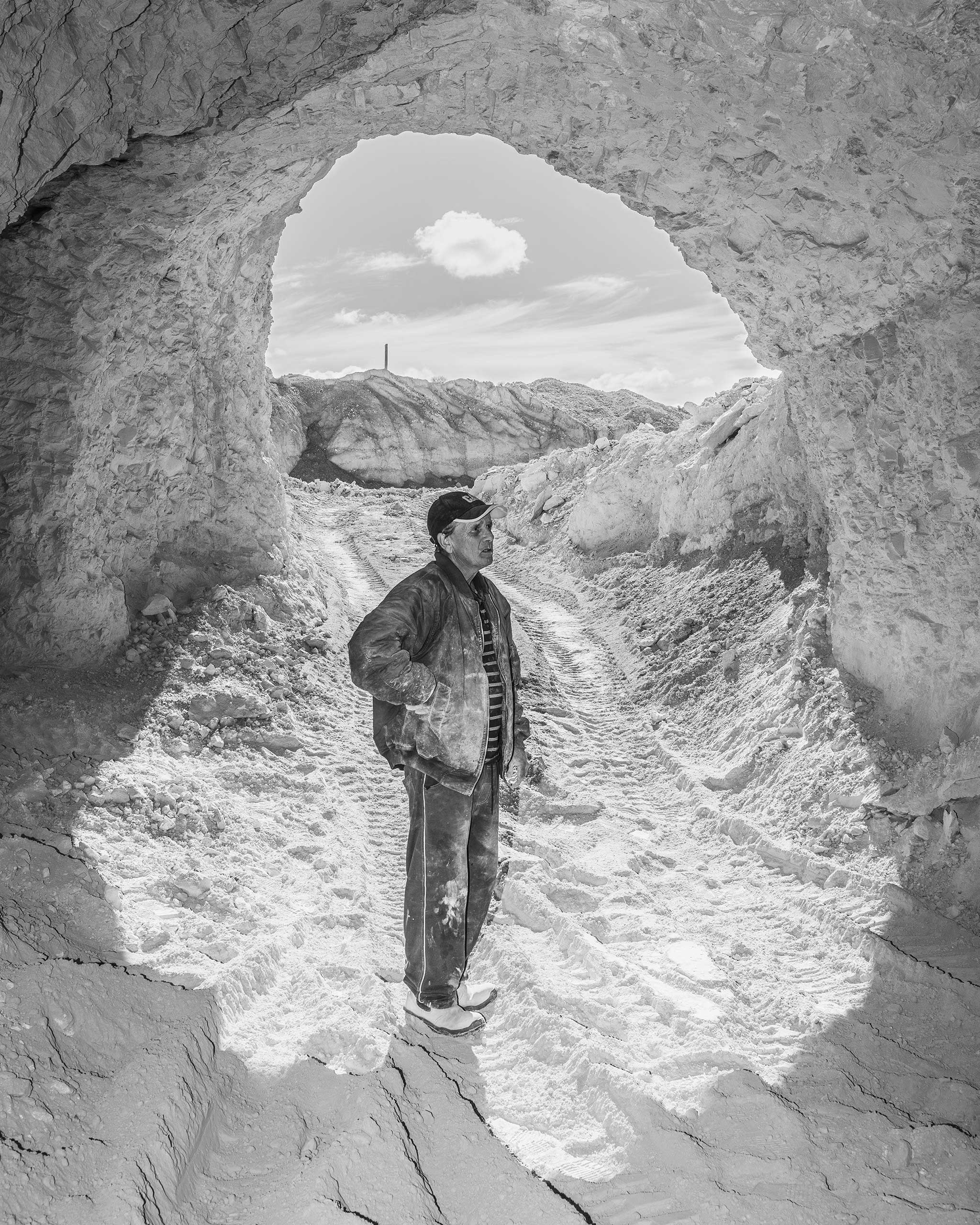

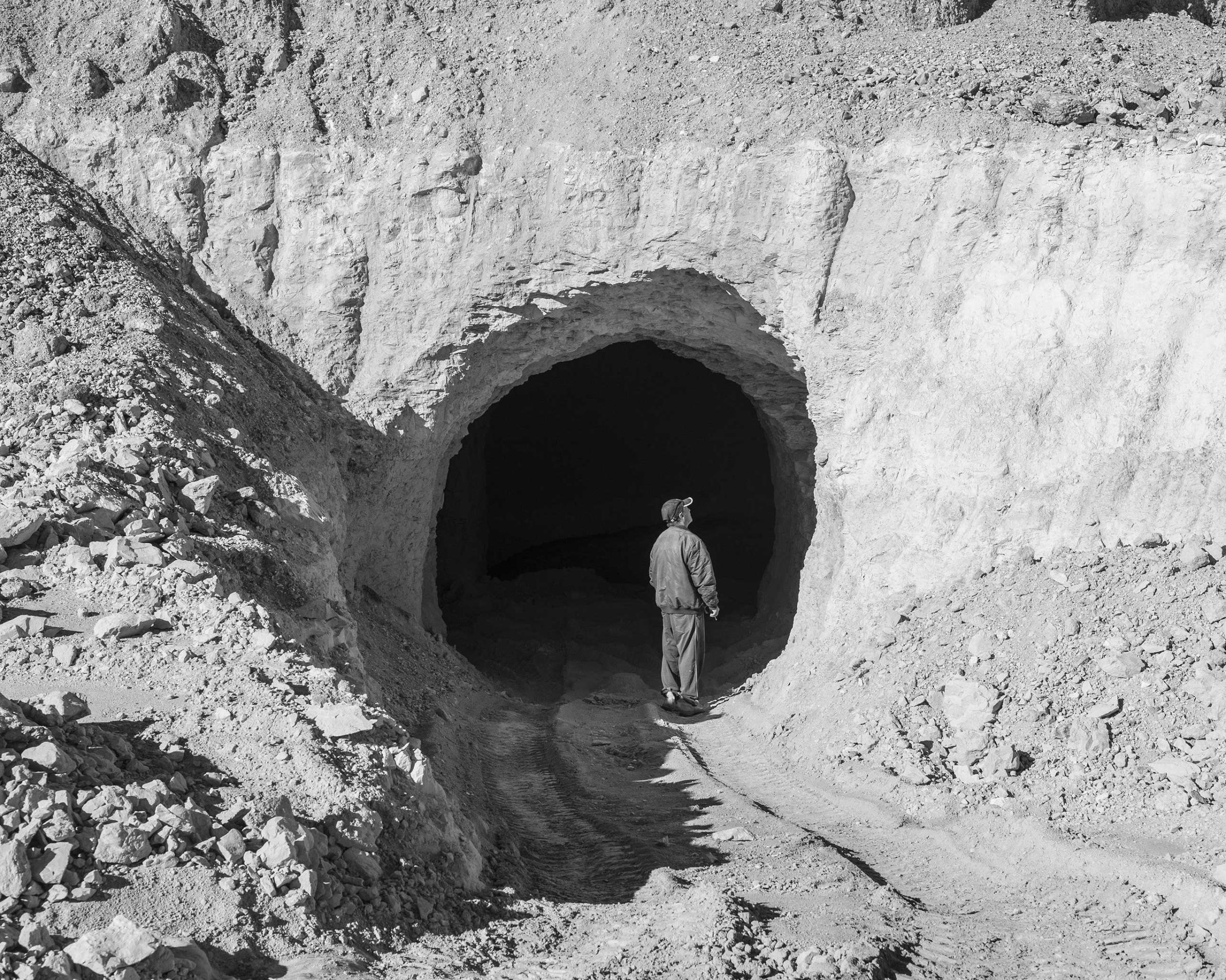

Coober Pedy, an isolated town in the middle of the southern Australian desert, is scarred by man’s greed. A lust for opal riches has left the once flat landscape pockmarked with hundreds of thousands of holes and accompanying hills. Against the infinite flatness of the surrounding desert, the sight is surreal. But what lies beneath is even stranger.

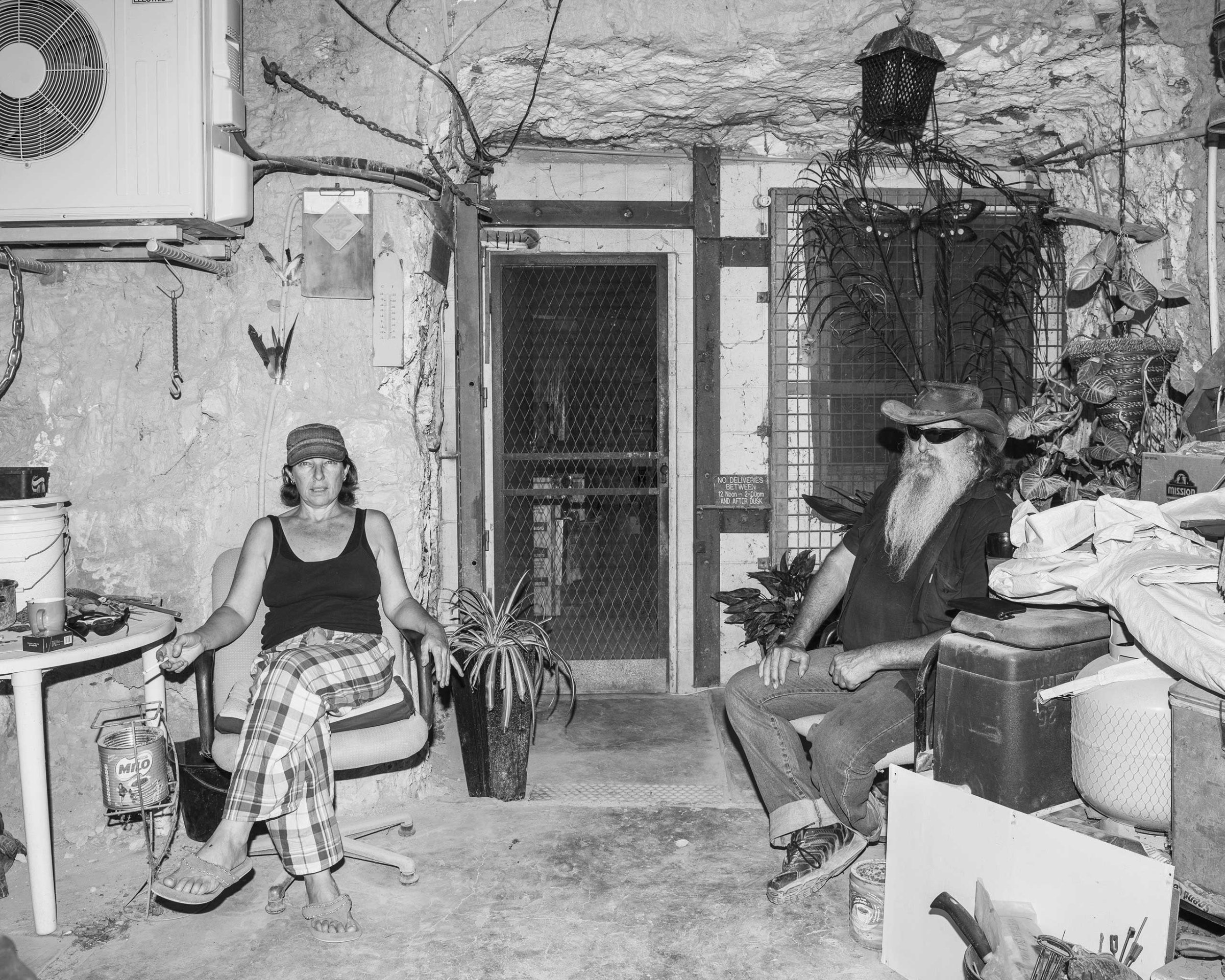

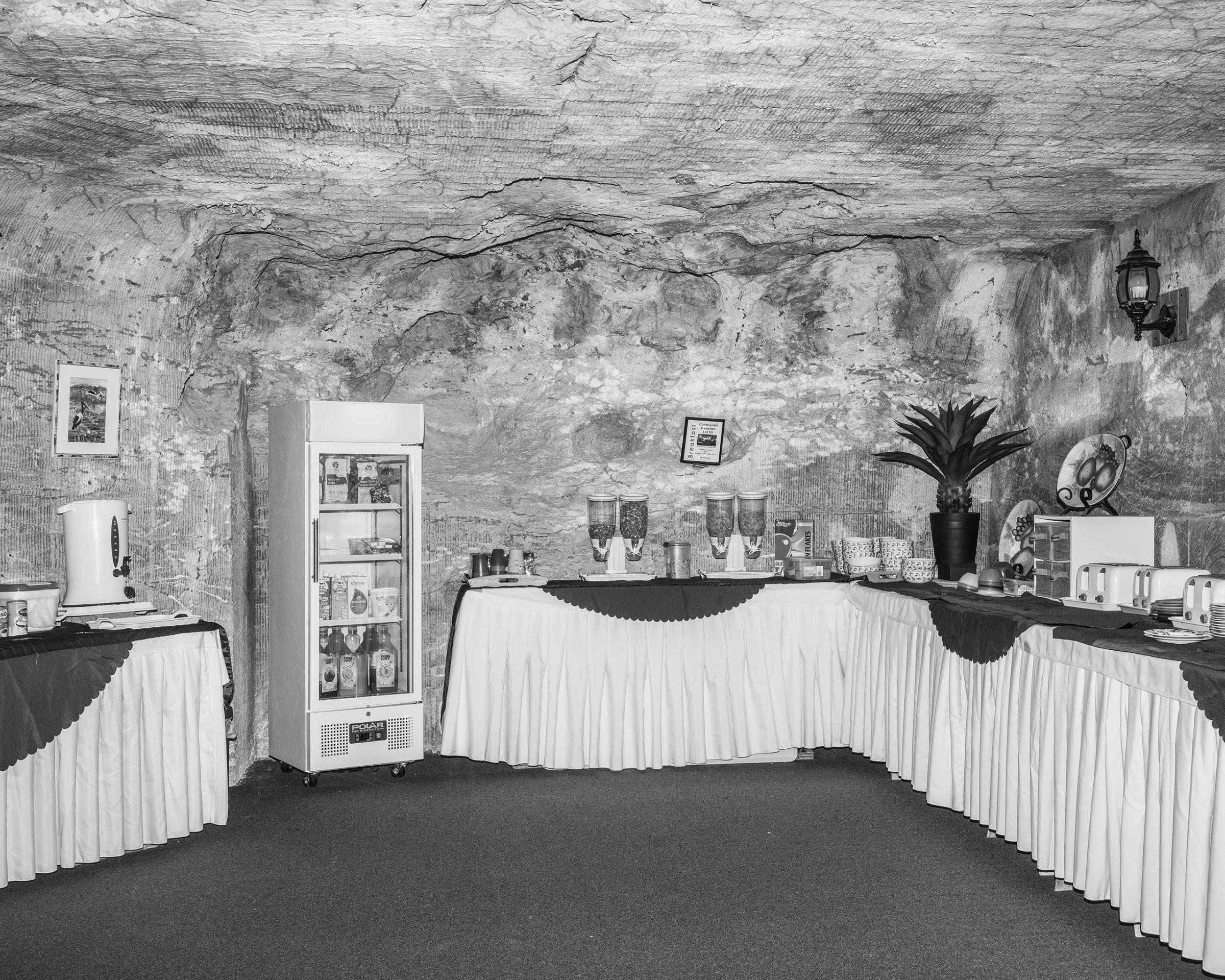

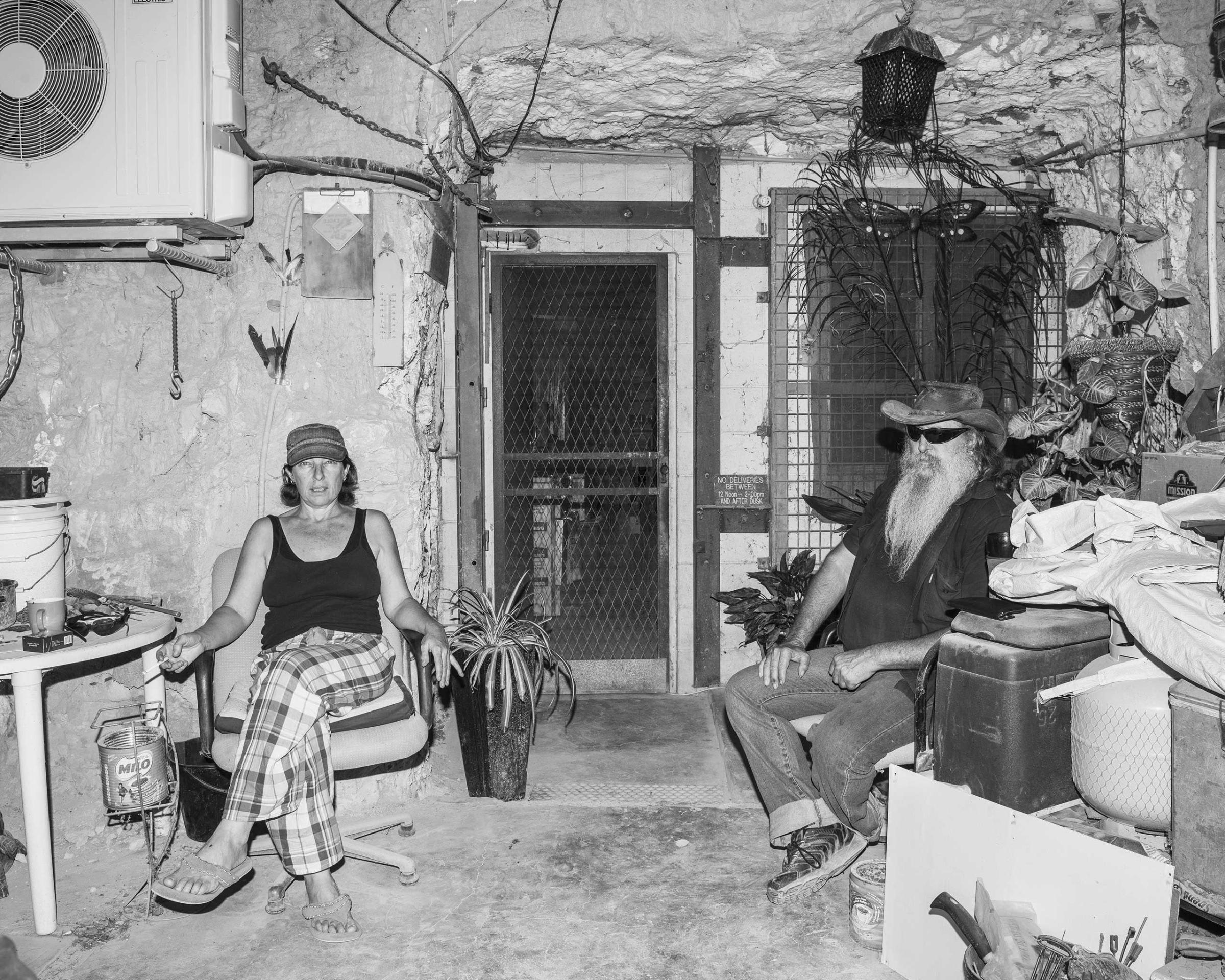

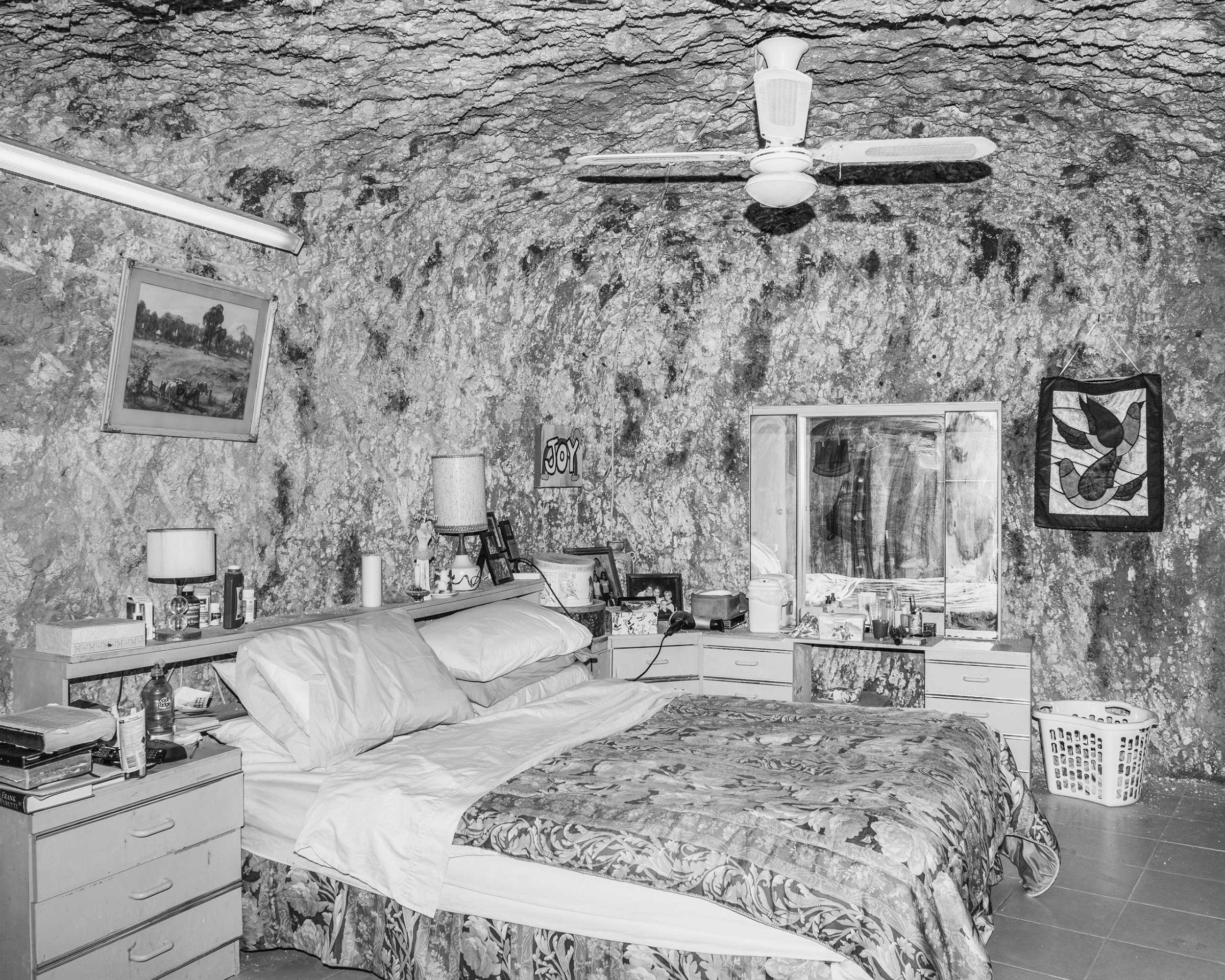

The town’s population mostly reside underground, in a subterranean world of shopping malls, schools, churches and homes, all carved out of dusty cavities, once mined for opals. They are guardians of a bloody history, now inhabitants of its dingy present. Theirs is a topography of fake horizons forced by manmade expansion, at once bleak and skeletal but also bristling with irresistible kitsch. It’s a place of extremes; not just the bizarre infrastructure but also the intolerable heat. In high summer, temperatures sore to 113º F.

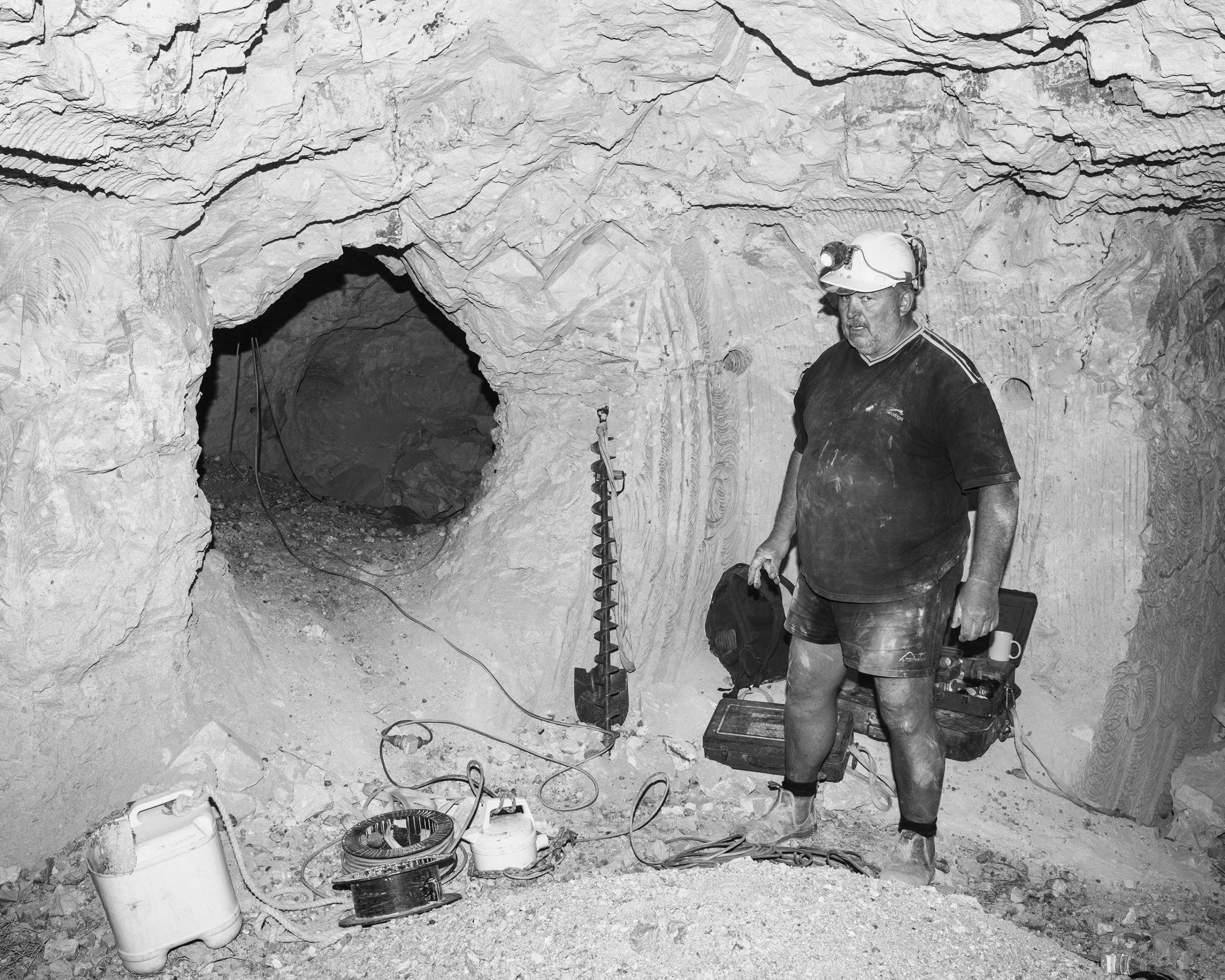

“I was really amazed by the manufactured landscape, with all the little mountains all over the place with millions of holes,” says photographer Antoine Bruy, who spent a month documenting the town. “They’ve been digging the place for over a century now. The Golden Age was during the 1970s through to the 90s.” But what used to be the opal capital of the world, is now reduced to 70-odd men fighting over dust. “It is more like fishing than mining,” Bruy adds. Now the town’s main income is tourism, though that also draws little money, despite a brief flush in the 90s.

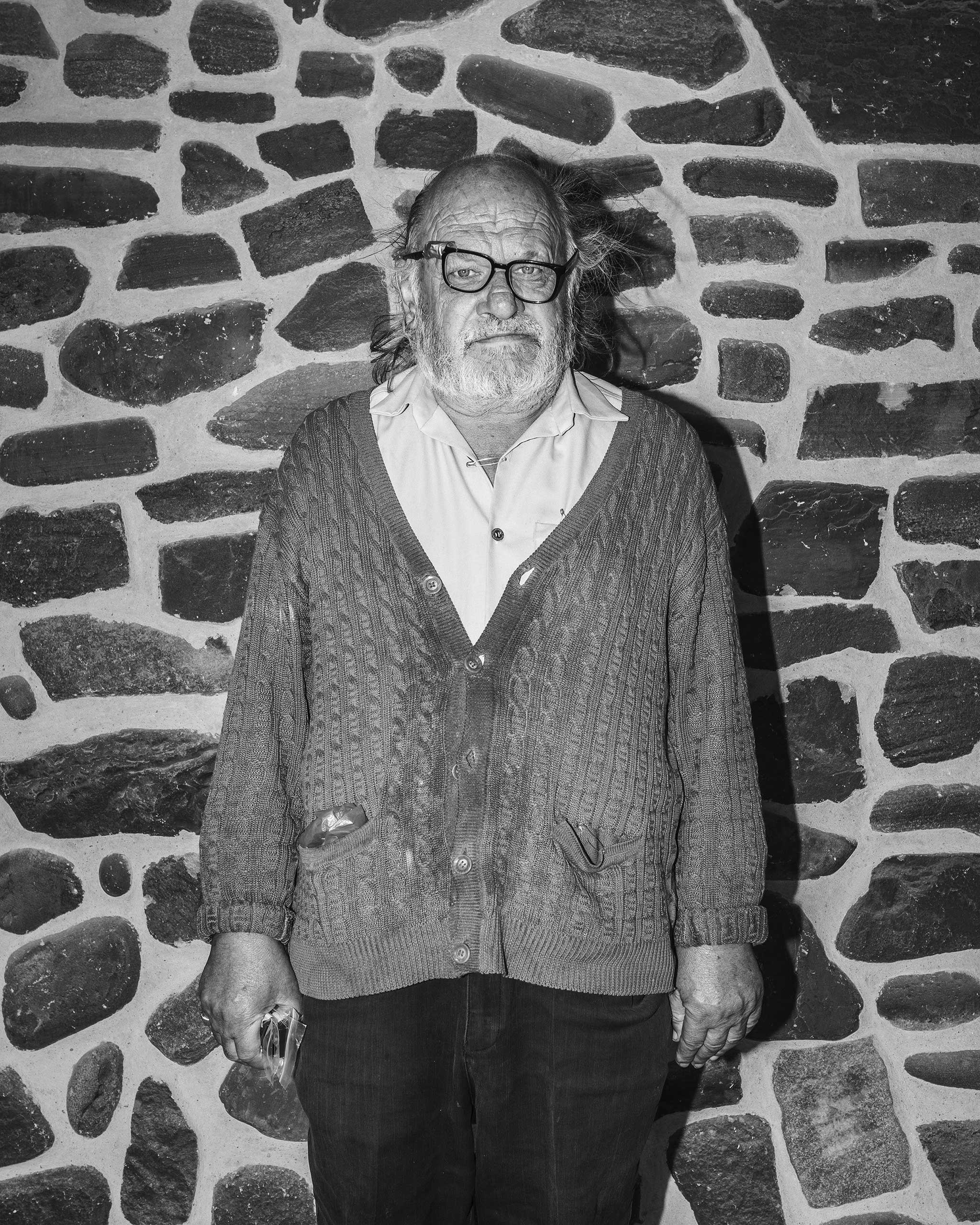

For Bruy, the story was as much about the people as the place, and the characters he spent time with revealed another layer to Pedy’s rich history. Few young people live there now; most move to Adelaide as soon as they’re old enough. Those who do remain have mostly been there for 20 or 30 years. One man named Bill, who was once a teacher, has fallen into a state of destitution and now makes a living selling cheap opals to tourists. “He showed another aspect of this place, how it can send someone a little crazy,” Bruy says. “Maybe because of alcohol or [lack of work] or because of the lifestyle.”

The past still lingers in Pedy’s gloomy caverns. “Somehow, you can feel the stories. There is something really strong,” says Bruy. “Then you start talking to the older miners and realize that the stories are even [crazier] than you could have thought.” Old tales of miners killing each other for precious opals are common. “I also heard a lot about people who kept digging hoping to find more and more opals – knowing they should stop – and dying because rocks above their heads just collapsed,” he adds.

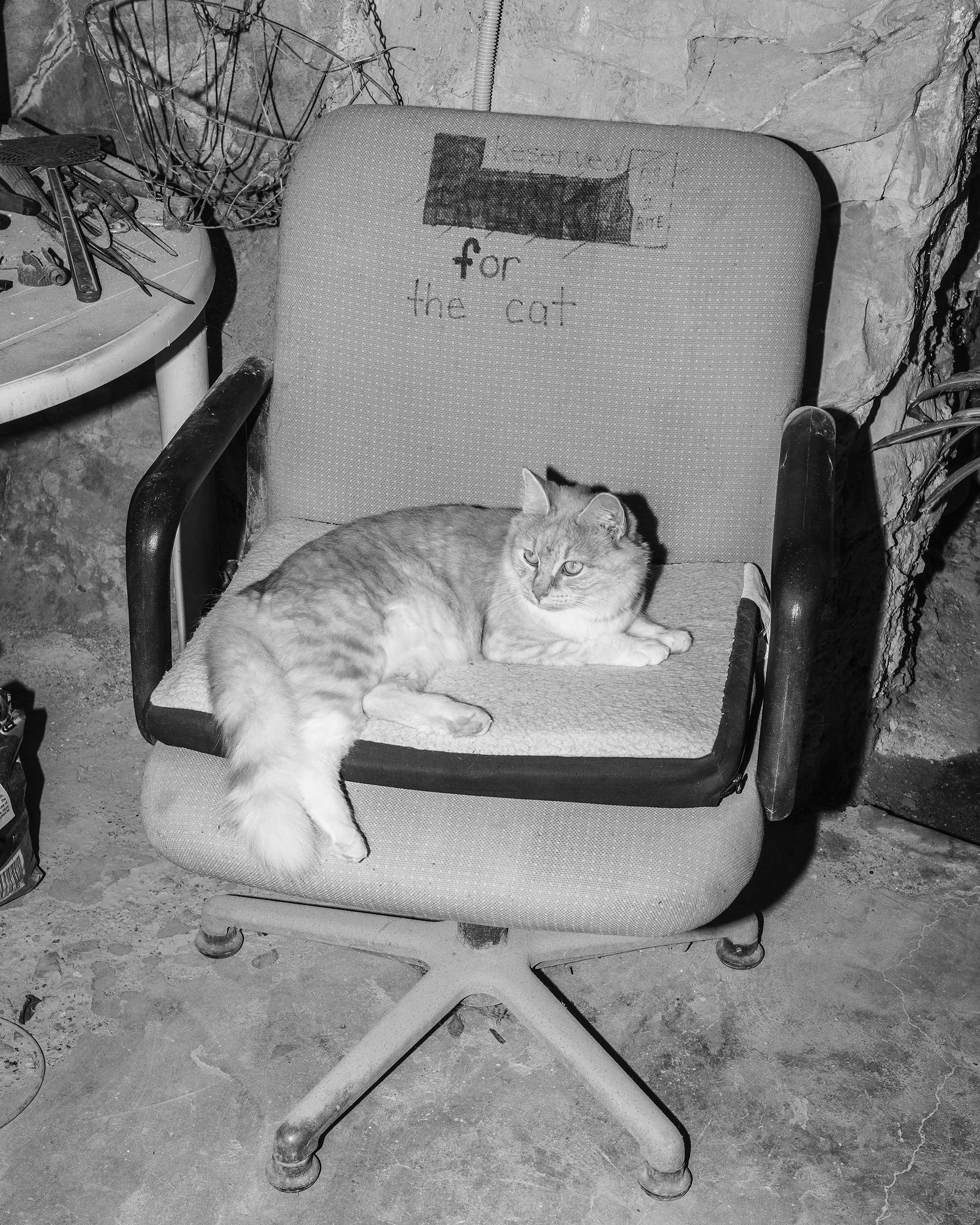

It was the isolation of the town that first drew Bruy in, but the normalcy of everyday life that brought him closer to the heart of the story. “To an outsider the place looks really amazing and weird,” he says. “But when you go there actually it’s just their daily life. It’s very common to have a dugout, to live underground.” Bruy says it felt like any other small community; close-knit and gossipy, suspicious of strangers.

Despite this sense of normality, the lines between fact and fiction are easily blurred. The town has doubled as a film set for blockbusters like Mad Max and Until the End of the World and remnants – like a UFO house and space ship from Pitch Black – litter the streets. It is a testament to the town’s eccentricity that neither seem out of place. “[The UFO] fits to the place,” says Bruy.

Bruy played on this ambiguity through his visual approach. He decided to photograph in black-and-white to avoid any obvious signifiers of the Australian outback. “You have this red dirt and this very blue dense sky that is so familiar to Australia,” says Bruy. “Using black-and-white added to the potential that this was some sort of fiction. You take the color away and it becomes a little bit more abstract somehow.”

Antoine Bruy is a French photographer based in Lille, France. White Man’s Hole is part of an ongoing series called Outback Mythologies. View more of his work here.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com