In 1883, Charles F. Thwing, a minister with deep interest in higher education, published a study of American colleges. In his chapter 3, entitled “Morals,” he asserted that a significant number of city-bred college students “are immoral on their entering college” because the city environment has “for many of them been excellent preparatory schools for Sophomoric dissipation” and “even home influences . . . have failed to outweigh the evil attractions of the gambling table and its accessories.” In contrast, students from rural settings have been deeply elevated by “not only the purity of the student’s home but the associations of his country life.” Moreover, he explained, the higher rates of immorality among students in colleges “located in or near cities” reflected “the character and surroundings of the colleges.”

…Many writers, intellectuals, and government officials expressed deep concern about how the growth of cities could undermine traditional American values. Anti-urbanism dated back to the colonial era and took on special importance after independence, in discussions of the meaning of American “democracy.” In 1784, Thomas Jefferson wrote that “the mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body.” Three years later, he assured James Madison that “our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries as long as they are chiefly agricultural.” In the 1850s, a writer to the Prairie Farmer, published in Chicago, complained that city life “crushes, enslaves and ruins so many thousands of our young men, who are insensibly made the victims of dissipation, of reckless speculation, and of ultimate crime.” In 1885, the Reverend Josiah Strong, a prominent leader of a movement to use Protestant religious principles in solving the problems brought on by urbanization, industrialization, and immigration, published Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis. In this widely read book, he presented a list of “perils” facing the country, one being “the city,” which he described as “a serious menace to our civilization.”

Anti-urbanism took on political significance in the election of 1896, when the populist Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan campaigned against the gold standard. In his famous speech in favor of the free coinage of silver, Bryan dismissed the argument that “the great cities are in favor of the gold standard,” asserting: “Burn down your cities and leave our farms and your cities will spring up again as if by magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.”

Urban civic and governmental leaders, whether or not they accepted this negative view of cities, worked to build parks and plant trees in their communities. Advocates for creating a major park in New York City argued that it would improve the health of residents and the behavior of working-class people. The poet William Cullen Bryant, editor of the New York Evening Post, called for a new park in an 1844 editorial, arguing that parks contribute “to the health . . . and the morals of the community.” In 1853 he asserted that the proposed park would create “fewer inducements to open drinking houses.” The first portion of Central Park opened to the public in 1858. Many other cities also built major parks, and a national movement developed to encourage reforestation not only in cities but across the country.

From the beginning of the 19th century, leaders of private American colleges, founded largely by Protestant denominations, shared Reverend Thwing’s concerns about the negative influence of cities. Like Thwing, Louis A. Dunn, a Baptist minister and president of the Central University of Iowa, published a short history of the American college, in 1876. He concluded, “Colleges located in quiet rural towns, do accomplish more work and better work . . . than in other localities,” and “large cities, business centres, places where the people congregate . . . should never be chosen” as a location for a college.

Public college leaders, too, often opposed city locations. The founders and supporters of these colleges believed deeply that college education must build character and spiritual values in the small number of young men who attended public institutions. To inculcate these values colleges should not only isolate students from the negative influences of cities but also surround students with trees, shrubs, and the vegetation of the countryside. Colleges built dormitories, had students eat at campus dining halls, and developed elaborate extracurricular programs to foster a deep sense of institutional community, what historian Frederick Rudolph termed “the collegiate way.”

Before winning election as U.S. president, Woodrow Wilson was a professor at, and later president of, Princeton University, an elite, historic institution with a self-contained rural campus. Wilson argued that college should promote “liberal culture” for a select group of men capable of appreciating “moral, intellectual, and aesthetic values.” This education prepared them for national service and civic leadership. However, it was not appropriate “for the majority who carry forward the common labor of the world.” It could be accomplished only in a “compact and homogeneous” residential college. “You cannot go to college on a streetcar and know what college means,” Wilson asserted.

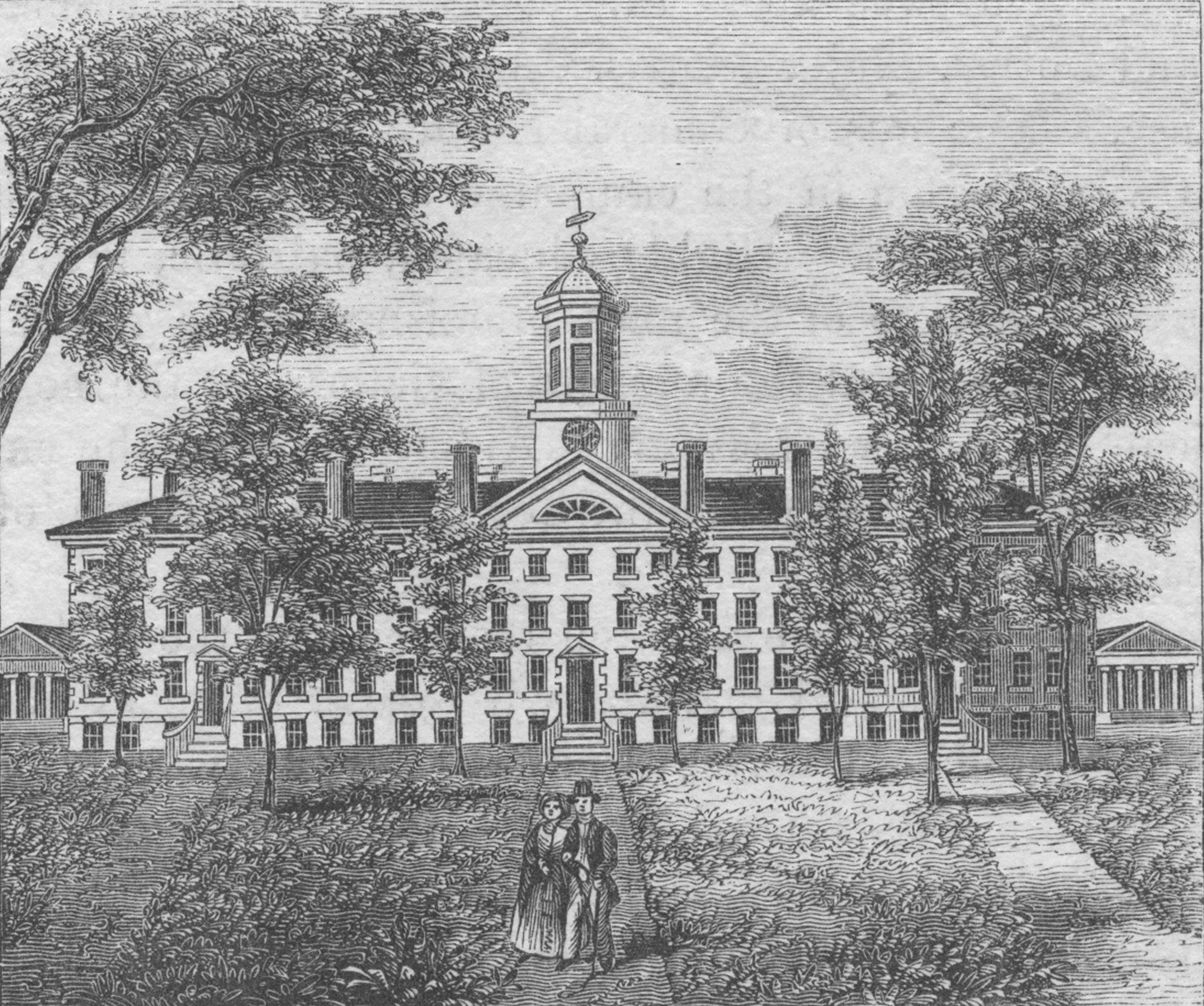

A small number of private women’s colleges opened in the 19th century, and they also sought to build student character at locations far removed from the negative influences of the city. However, their founders and leaders did not develop rural campuses like those built for men. They believed that women students had to be supervised day and night by college staff, so each institution built a large, self-contained building within which students would live, eat, attend class, and study. In the years after the Civil War, some male institutions started to admit women, and others built separate women’s colleges within their institutions.

This excerpt is taken from Universities and Their Cities: Urban Higher Education in America by Steven J. Diner. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press © 2017. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com