It’s a very good thing for the world that Terry Virts did not smell ammonia on the morning of Jan. 14, 2015. He did hear a warning Klaxon go off — and a Klaxon aboard the International Space Station, where he was serving as part of a six-person crew at the time, sounds just as scary off of the Earth as it does on it. He also he saw a flurry of caution and warning lights blink on, one of which bore the letters ATM, indicating toxic atmosphere—in this case, toxified by leaking ammonia coolant, or so the on-board sensors indicated.

So Virts turned to a much more precise sensor—his nose—and he knew the stakes were high. “As they would tell us in training,” he said in a recent conversation with TIME, “if you smell ammonia, don’t worry for long, because you’re going to die.”

As it happened, Virts didn’t smell ammonia, but he and the other two astronauts in the American segment of the station nonetheless high-tailed it over to the Russian segment, where they use a different cooling system, slammed the hatch and camped out for 11 hours, until NASA and Roscosmos (the Russian space agency) traced the alarm to a faulty computer signal. Until the all-clear was given, Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin wanted there to be no mistake about the fact that while things may be tense between Washington and the Kremlin, all such differences stop at the atmosphere’s edge.

“He called up while we were there and said ‘our American colleagues, we want you to know you should stay as long as you want,'” Virts recalls.

That moment of cosmic collegiality is just one of the stories recounted in Virts’ dazzling new book View From Above. Published by National Geographic, and including a foreword by Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, the book goes on sale Oct. 3, 2017. Virts, who flew to space twice during his NASA career for a total of 213 days off the planet, is a disarmingly thoughtful astronaut, and the stories he tells both in his book and in conversation reflect that.

Astronaut Terry Virts: Best Space Photos

“Exploring space is such a fundamentally human thing,” he says. “I walk down the street and people don’t know who I am, but if I put my NASA jacket on, everyone wants to talk. It’s a universal fascination.”

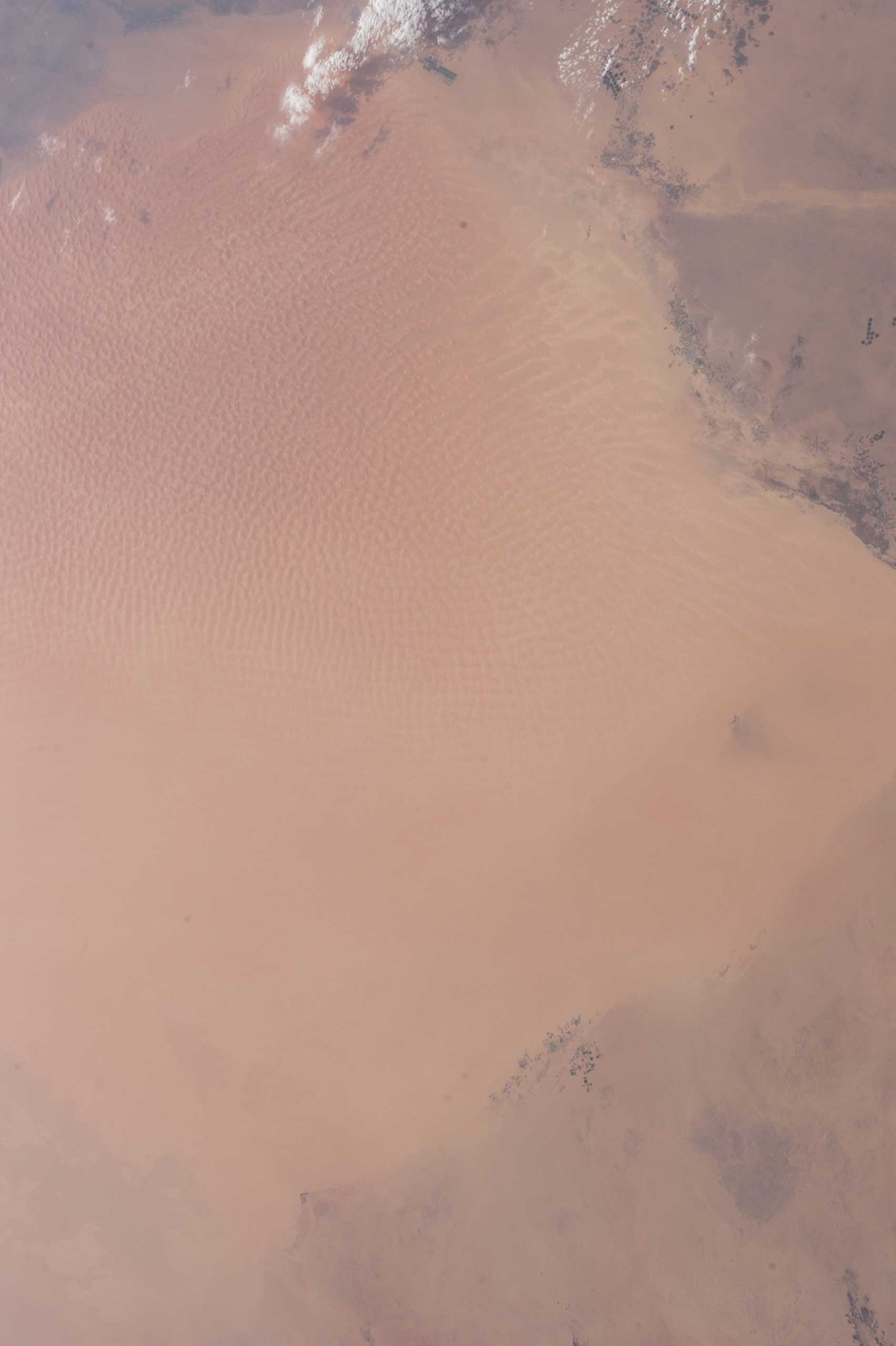

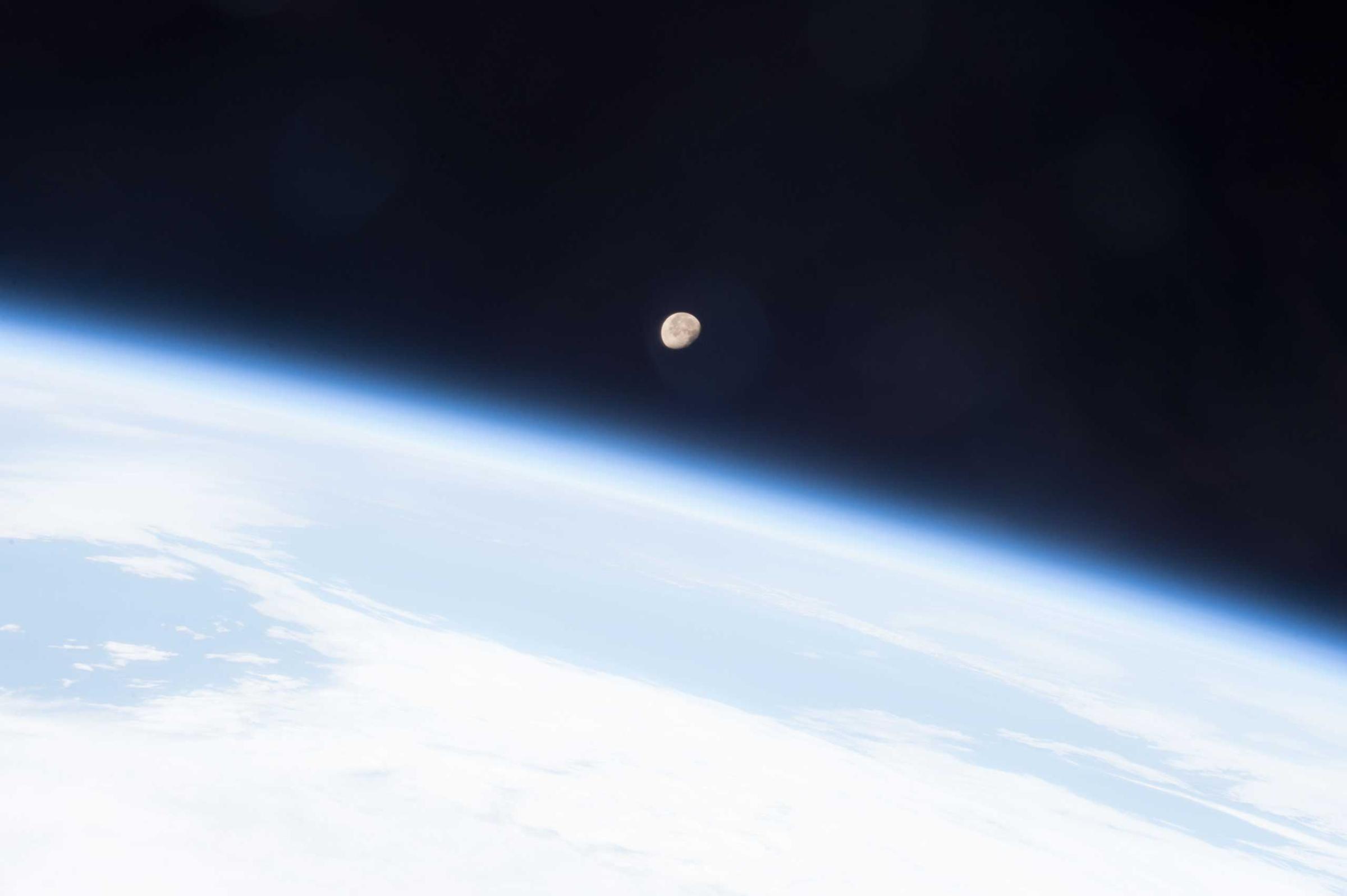

Virts’ book, however, is more than his stories; it’s also his pictures — dozens of vivid, often dizzying images not just of the Earth from space, but of the interior and exterior of the improbable skyliner that is the space station. This isn’t the first time he has distinguished himself as a space photographer. Just a few months after the ammonia emergency, TIME ran an online gallery of some of Virts’ other work. But with the time to think and curate and write, he has assembled a far richer gallery of what he saw and how he lived in the time he called space home.

For most of us, space travel will always be done by proxy — something we experience only through the journeys of others. That’s been true since the very first time humans left the planet. Thanks to Virts, however, that second-hand experience feels more first-hand than it ever has before.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com