An email from an arts advocacy group advises me to call my congressional representatives and tell them that art is a 700-hundred billion-dollar industry providing hundreds of millions of jobs. I must do this to save the National Endowment for the Arts, which President Donald Trump has now proposed eliminating through budget cuts. I can’t, though, and I do believe in the NEA. But if you do something for money, for a job, it’s not art, and the only way to help people make art is to give them spare time — not jobs. I want the NEA to support spare time for people who wouldn’t otherwise get it.

Poetry, generally considered to be one of the fine arts, derives from the Greek verb poiesis, which means “to make.” Yet poiesis is not merely a form of artistry: It is creation itself. All the fine arts, in fact, are methods of poiesis: acts of creation not constrained to fulfill any needs or purposes. This is the difference between the fine arts and the decorative arts.

Writing a poem is not saying what you mean in an unusual or “creative” way. To write a poem, to write creatively, is to immerse in a process of making and maybe discover an insight. The insight can be developed in revision, but it must arise in the writing process. This is difficult for people to grasp. People often use language to say what they mean. To use language as raw physical material, something to play with, with no intention to express a meaning — it’s difficult.

When writing a poem, you use your organs of sense perception to collect data, and then you organize the data, but not according to logic. The organization itself must be felt, and not thought out: You’re feeling for a physical coherence of linked images, pulses (rhythm), sounds (rhyme) and more. You’re building something, yet you’re not sure what — you’re not subordinating it to pre-existing ideas, meanings or purposes.

But you are not making nonsense. You’re rather making more sense than we often do. We use language to express our thoughts, but language has a way of shaping our thoughts, constraining them in ways we don’t realize. And writing poetry is a technique for cutting loose from these constraints — for turning away from the meanings we’re given and toward those we may find.

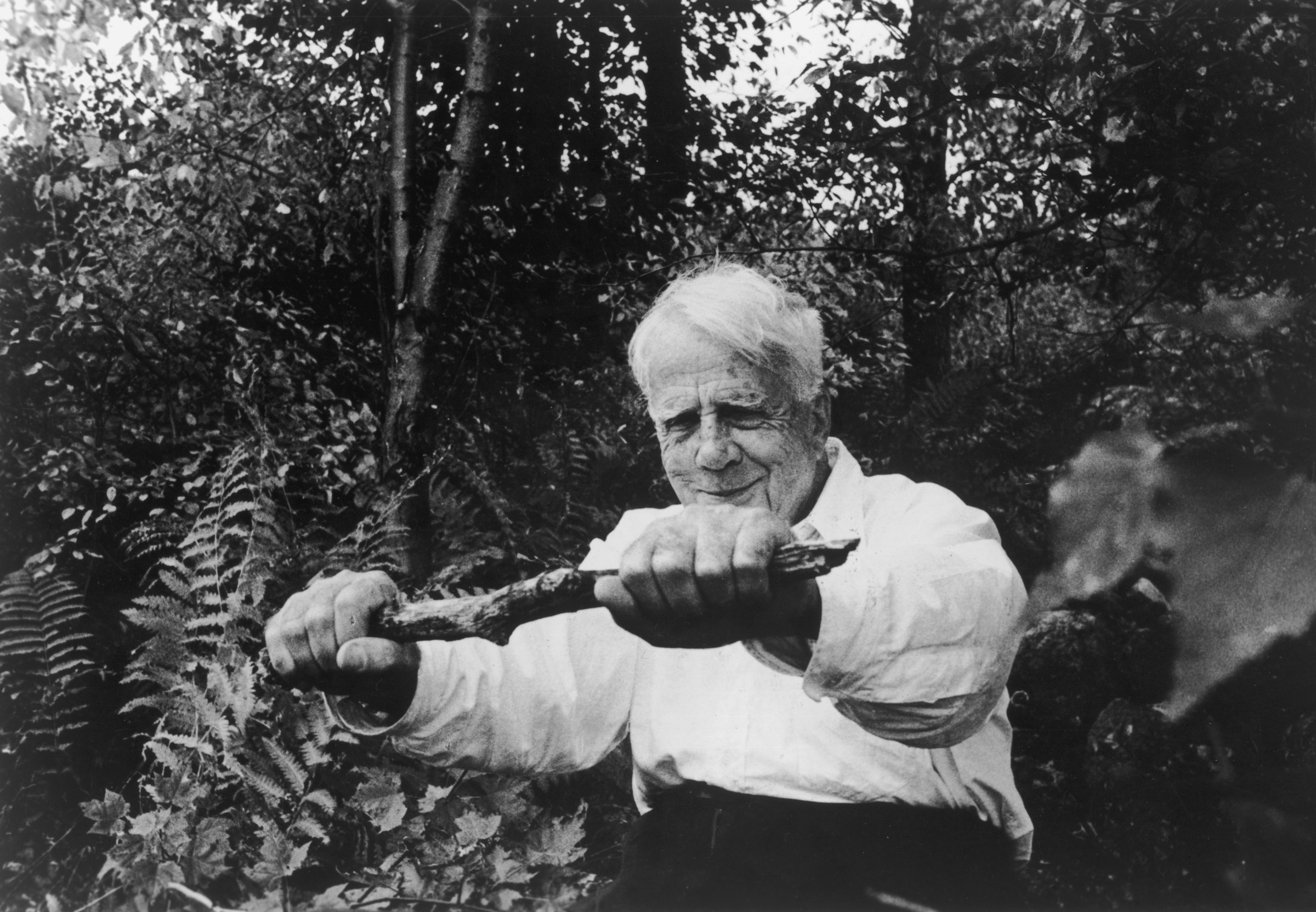

Robert Frost describes this process in his brief essay, “The Figure a Poem Makes”: “Step by step the wonder of unexpected supply keeps growing.” And many poems comment on it. “Anchor Head,” in Terrance Hayes’ Lighthead, winner of a 2010 National Book Award, offers, “my work, a form of rhythm/like the first sex,” a practice that involves “learning through leaning,” leaning on what’s real.

So, poetry — poiesis — is a highly concentrated and disciplined way of deriving knowledge from elemental, pre-verbal, sensory experience. As we are bodies — animals — we can have much in common. For this reason, sensory experience may be particular and expansive at the same time. The arts, like the sciences, are methods of inquiry, ways to know what’s real and ways to share this knowledge.

When I read a poem, I can tell if its “ah-ha” was discovered in-process, or if it was pre-fabricated and subsequently made “poetic” with pretty or unusual language. I can tell because I’ve been reading and writing poems for decades. The ability to know this is similar to knowing whether or not someone is lying. Knowing whether or not someone’s lying doesn’t require decades of study; it’s rather a matter of lived experience.

The email’s encouragement to talk up the benefits of the “arts and culture industry” seems part of a general trend to understand almost everything in terms of instrumental value: what we value because it can get us something else — what we can use to turn a profit. Politicians and headlines go on about jobs, for instance, and less about work. While work can be a pleasure, its own reward, a job is just a finite means to an end: a paycheck, security. Jobs are assigned; work is what we may share.

So, no poem, and no work of art, can be undertaken for profit: Art is not instrumental.

So, passionate as I am about the value of the arts, I will not call my representatives to tell them about the jobs and profits produced by the art industry. And I’m a poet at a university. I don’t earn a salary for writing poetry: I earn one for teaching people how to read and write poetry — economically irrelevant activities. To do what’s economically irrelevant is a basic right: It is freedom. Some are trying to turn a profit on this, but still others want to share it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com