This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

The role of death and how it might have affected American history and politics is demonstrated in so many situations in American history.

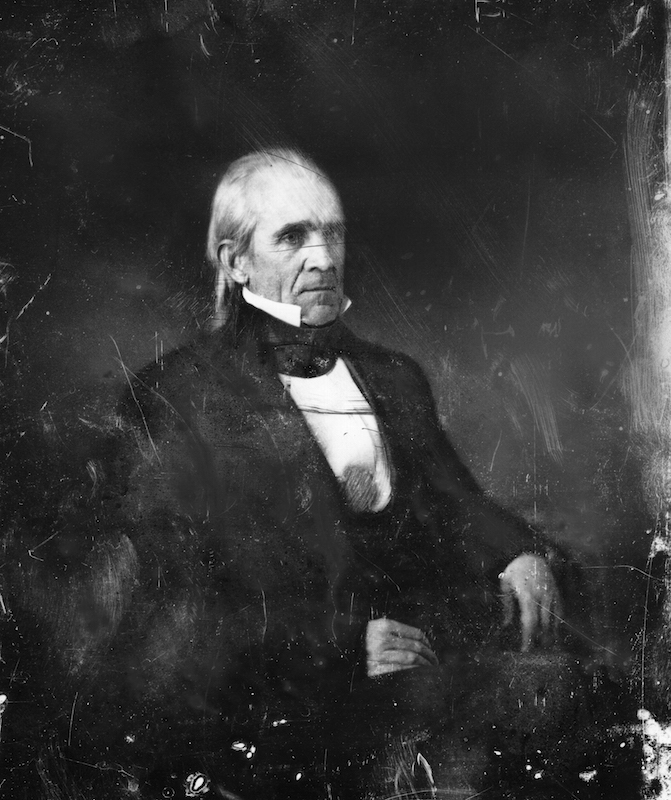

In 1848, President James K. Polk had triumphed in gaining new territory from Great Britain by treaty, and by war with Mexico. While the political battle raged over what was to be done with the Mexican Cession territories and the expansion of slavery, Polk chose not to run for reelection, the only time in American history that a President, willingly, chose not to seek a second term. It was a wise decision on Polk’s part, as he fell ill shortly after retirement, and died only 105 days after the end of his term in June 1849, the shortest retirement of any President in American history. So he avoided dying in office by retiring in time.

In 1860, Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas competed for the Presidency in a four-person race, losing to Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln. It was a bitter defeat, particularly after Douglas had defeated Lincoln two years earlier for his Illinois Senate seat. But the fact that Douglas lost was good for the nation, as he died three months into Lincoln’s term, in June 1861, as the Civil War raged on.

In 1872, Democratic Presidential nominee Horace Greeley lost the election to President Ulysses S. Grant, and then died three weeks after the election, at the end of November 1872. Never before or since has a Presidential contender died after the election and before the inauguration, and in this situation, the Electoral College had not yet met, but Greeley’s electoral votes were split among several people, with Vice Presidential nominee B. Gratz Brown of Missouri gaining the most. Had Greeley won the Presidency, Brown would have been the Democratic President elect to replace the dead Greeley.

In 1884, President Chester Alan Arthur, who had replaced the assassinated James A. Garfield in September 1881, wanted to be the Republican Presidential nominee for a full term, but the convention rejected him and chose James G. Blaine instead. Never again would a sitting President be denied renomination. However, it was a fortunate event; if Arthur had run and won a full term, he would have died in office of Bright’s Disease, also known as Nephritis (a kidney disease), in November 1886, the second such Presidential death in five years.

In November 1899, Vice President Garret Hobart under President William McKinley’s Presidency died in office of heart disease. There was no Vice President for almost sixteen months, until Theodore Roosevelt became McKinley’s second term Vice President. Since Hobart was well liked and active as Vice President in the first McKinley term, it seems clear that he would have remained on the ticket in 1900, and would have been President instead of TR, had he lived, after McKinley was assassinated in September 1901.

In 1912, President William Howard Taft was on the way to a resounding defeat for reelection when Vice President James Sherman died at the end of October, only a little more than a week before the election. When the Electoral College met, Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler replaced Sherman on the Electoral College ballot, which only gave him and President Taft the miniscule number of 8 electoral votes from Vermont and Utah, the worst Presidential defeat in American history. Never otherwise has a Vice President died at the time of an election.

In 1940, Wendell Willkie and Charles McNary were the losing candidates to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Henry A. Wallace, and both Republican candidates died during that term, with McNary dying in February 1944, and Willkie just before the 1944 Presidential election, in October 1944. Had they won the 1940 election, both would have passed away at a crucial time in World War II, before and after D Day in June, and just weeks before what likely would have been a reelection campaign by President Willkie, after the national conventions had taken place.

In 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower won a tough battle for the Republican Party Presidential nomination over “Mr. Conservative Republican” Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, son of President William Howard Taft. Taft had tried for the nomination throughout the 1940s, and this was his last attempt at running for the office his father had held. Taft was a loyal supporter of Eisenhower once he lost the nomination, but it was indeed fortunate that Taft did not win the nomination, because in May 1953, just three and a half months after the inauguration of Eisenhower, Taft was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor, and he passed away in July 1953. Had he been President, he would have only served six months, with most of the time being seriously ill.

When Harry Truman decided to retire after seven years and nine months in the Presidency, at the time of the 1952 campaign, his second term Vice President, Alben Barkley, who had been an active participant, wished to run to replace Truman, but it was argued that his age of 75 made him too old to run, and his campaign faltered. That was fortunate, as Barkley died in April 1956 at age 78, and therefore would have died during the term he wished to serve as President.

In 1992, Massachusetts Senator Paul Tsongas was the front runner for the Democratic Presidential nomination for a substantial time, but lost the nomination to Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton. It was known that Tsongas had left the US Senate in 1985 due to a diagnosis of cancer, which was in remission by 1992. But the cancer returned during the first term of Clinton, and Tsongas died two days before the end of the first Clinton term, January 18, 1997, which would have meant he would have died in office two days before the end of the term he campaigned for to be President.

So death would have affected American history and politics in ten situations, had history turned out differently than it did.

Ronald L. Feinman is the author of Assassinations, Threats, and the American Presidency: From Andrew Jackson to Barack Obama, Rowman Littlefield Publishers, August 2015, now out in paperback.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com