After two tours in Iraq and a stay at Walter Reed hospital, photographer and veteran Michael McCoy found himself at a turning point. Until that moment, photography had been a hobby of sorts, a personal habit that played a minor role in his life.

“On my first trip to Iraq, I would take tons of pictures to keep up the morale and to send back to friends and family,” he tells TIME. “I had everything backed up to a hard drive and I lost that hard drive, which was very hurtful because I had pictures of family members that are deceased. I realized the only thing I could do was document life in the present.”

The loss of a hard drive—every photographer’s worst nightmare—while devastating at first, spurred McCoy to document some of today’s most pressing controversies, such as the riots that followed Freddie Gray’s death. He says that losing those photographs caused him to look at life differently.

But photography also serves another purpose for him: an escape. McCoy suffers from post traumatic stress disorder, and he says that taking photos has helped him process the more difficult aspects of his time in the army. “It provided me an outlet to take the edge off of past experiences, trauma from Iraq, stressors. It allowed me to be in my own little world. It gave me a better voice. It’s teaching me to be a little more careful. It teaches me to observe more,” he says. “The only thing that comes across my mind when I have that camera in my hands is escaping the memories of being in a combat zone.”

McCoy, who is a native of Baltimore, witnessed his hometown being consumed by Freddie Gray’s death. “Seeing this happen to your city… I was disappointed,” he says. “But at the end of the day it’s all about accountability. I hope that the pictures I take could reach a viewer to demand accountability from the people that they elected to office, and the people that are chosen to serve. And to see that all police officers, and all protesters, aren’t bad people.”

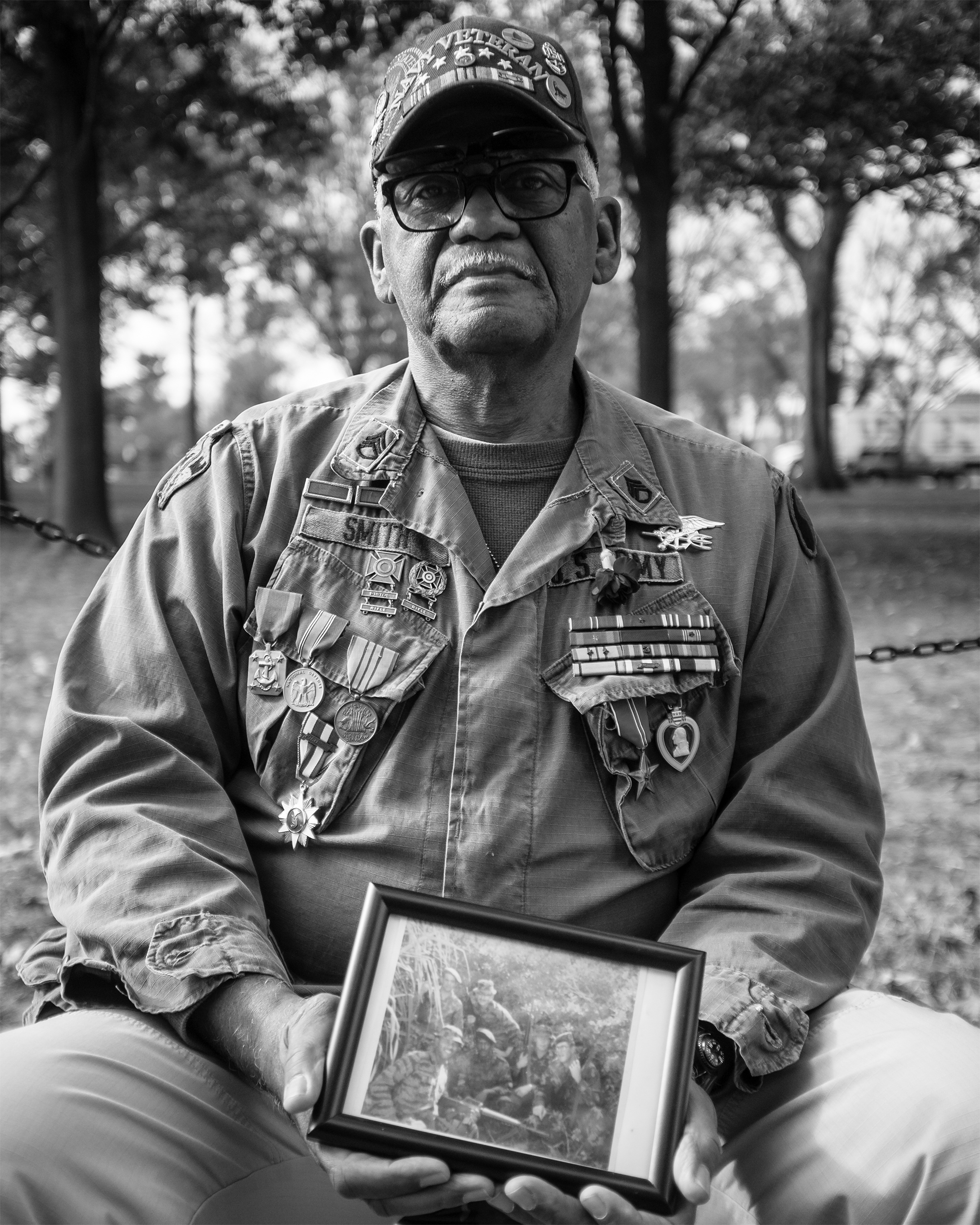

In the future, McCoy hopes to use his photography to educate people about PTSD. “Society has painted a picture that PTSD isn’t real, and that it doesn’t have a face,” he says. “These are wounds that aren’t really visible. I want to bring awareness to the public. Just because someone looks good on the outside doesn’t mean they’re not hurting on the inside.”

For veterans like McCoy, PTSD is an enduring struggle, one that can be surrounded by shame and misunderstanding. “We’re still people, we’re still human, and we just want to be treated as such,” he says. “It’s something that just doesn’t go away. It’s a fight that you’re going to live with for the rest of your life.”

Michael McCoy is a photographer based in Baltimore. He was selected as one of the African-American photographers to follow in 2017. Follow him on Instagram.

Myles Little, who edited this photo essay, is a senior photo editor at TIME.

Janna Dotschkal is a freelance writer based in Washington.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com