Milestone moments do not a year make. Often, it’s the smaller news stories that add up, gradually, to big history. With that in mind, in 2017 TIME History will revisit the entire year of 1967, week by week, as it was reported in the pages of TIME, to see how it all comes together. Catch up on last week’s installment here.

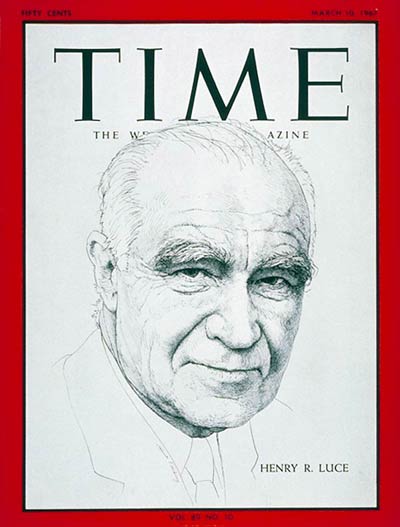

When magazine magnate Henry Luce died at 68 on Feb. 28, 1967 — almost exactly 44 years after the date on the cover of the first issue of TIME — his final memo to the magazine’s editors was still in transit. Luce, who had founded TIME with his Yale classmate Briton Hadden in the years after World War I, had already begun to delegate his duties at the company. (In 1960, he ceded corporate control of Time Inc. and in 1964 he stepped down as Editor in Chief of TIME.) Nevertheless, he remained closely tied to the daily operations of the publications he had launched.

Such a set-up made sense, as TIME and its sister publications had borne Luce’s fingerprints since their founding. One place where that deep involvement could be seen, the magazine’s remembrance explained, was in the way his magazine’s reflected his sense of right and wrong — moral rectitude but also factual correctness.

And that was something worth noting:

When TIME was founded, the nation’s technology and communications had far outstripped its daily newspapers, which remained local, parochial and, for the most part, ineffably stodgy; the few magazines of comment were not widely circulated. “I do not know any problem in journalism,” Luce said later, “which can be usefully isolated from the profoundest questions of man’s fate.” Yet, he allowed mischievously: “I am all for titillating trivialities. I am all for the epic touch. I could almost say that everything in TIME should be either titillating or epic or starkly, supercurtly factual.”

TIME’s blend of the epic and the titillating, its telling of news in terms of people, its belief that medicine, art, business, religion, education and many other aspects of everyday life that were largely ignored by the daily press were all newsworthy in themselves, made the magazine a success almost from the start. Most important of all was its founders’ guiding concept that the newspaperman’s sacrosanct “objectivity” was a myth. Asked once why TIME did not present “two sides to a story,” Luce replied: “Are there not more likely to be three sides or 30 sides?”

Luce’s journalistic theory certainly appealed to readers. One telling anecdote from the 1967 remembrance recalls how the launch of LIFE in 1936 nearly killed Time Inc. — it was so successful that the company could barely afford the paper needed to print enough copies to satisfy demand. Luce would later reflect on the importance of that success: “I have sometimes said to myself that the one thing I was determined to do was to make ‘journalist’ a good word. And today it, is a good word.”

It’s also worth reading the full letter from the staff that appeared at the front of the issue, too, for personal recollections of what it was like to work with Luce.

Vietnam update: After a brief period of optimism about the prospect of peace in Vietnam, the war had once again turned bleak. Though President Johnson wouldn’t say that new moves constituted “escalation” of military involvement, TIME reported that he admitted that recent violence had been “more far-reaching” than had previously been the case, as many in Washington showed signs of losing faith that an end could be achieved via negotiation. But that belief was far from universal: Bobby Kennedy, then a Senator, spoke out with a major speech urging a halt to bombing.

Nazis found: A story in the world-news section related how Simon Wiesenthal, in pursuit of Nazi war criminals, had tracked down Franz Stangl, an infamous leader of the Treblinka concentration camp. After paying an informant, Wiesenthal was able to direct Brazilian police to Stangl’s home in Sao Paulo, where they took the Austrian fugitive — who was No. 4 on Wiesenthal’s list of most-wanted Nazis — into custody.

Window to the past: A new fad touted in the “modern living” section traced the 1920s origins of tinted car windows as “purdah glass” that allowed observant Muslim and Hindu women to travel in cars without violating their religious seclusion. By 1967, however, the technology was popular among celebrities in London — even though those who used it had discovered an inherent problem with it. “It is so noticeable that the instantly curious flock around to try penetrating its secrets,” TIME noted, “let an ordinary clear-windowed car go by without a second glance.”

Great vintage ad: This AT&T ad — about how wrong numbers are annoying — shows that everyone who tweets at his or her cable company is part of a long history of annoyance with service providers.

Coming up next week: The Redgraves

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com