The digital cloud is built on invisibility. Instead of books, DVDs, CDs, newspapers or magazines, we have pure data, traveling back and forth between our web-connected devices. Everything we want is at our fingertips, and all we need to do is push a button.

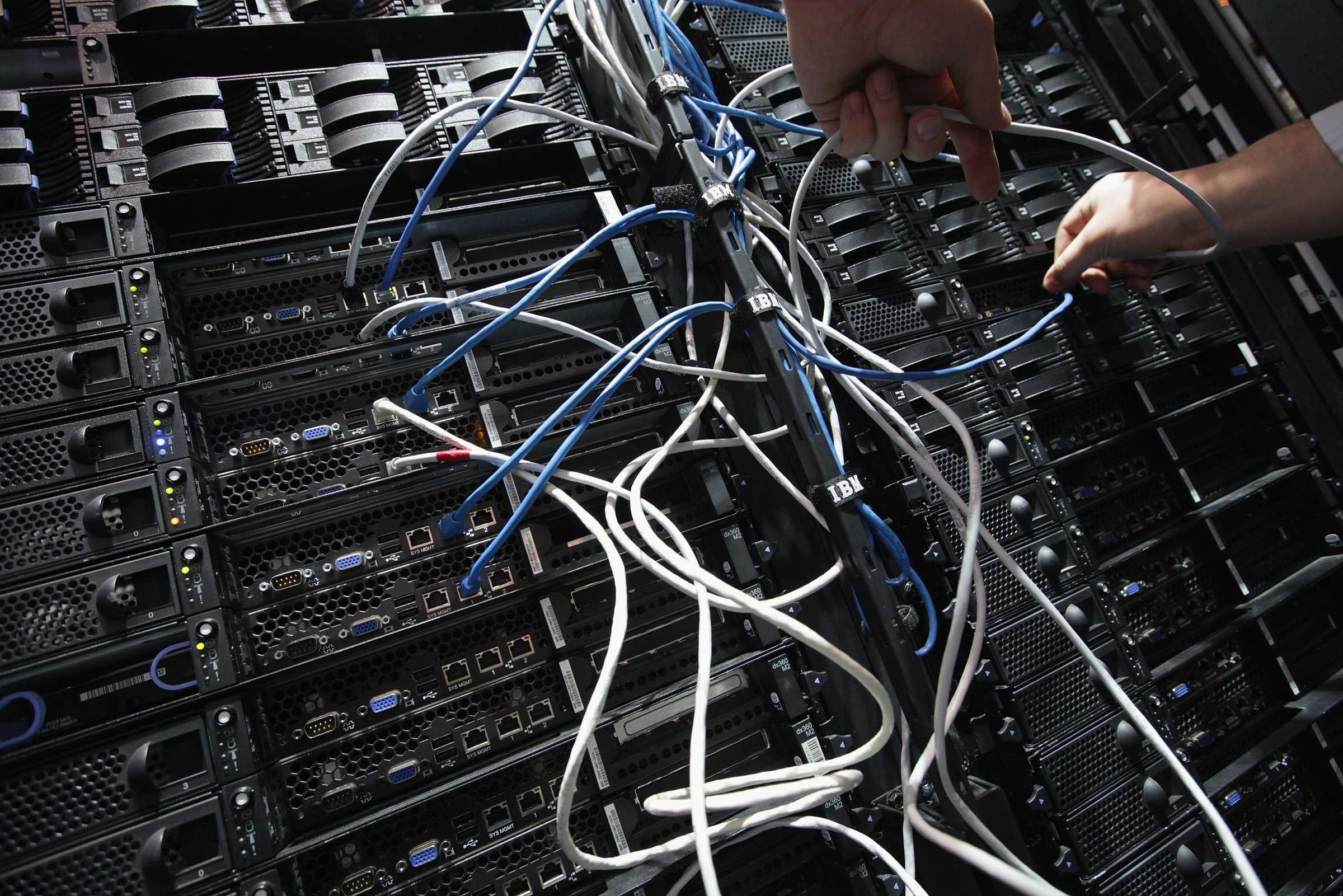

But the digital cloud has a physical substance: thousands upon thousands of computer servers, which store the data that makes up the Internet. And those servers aren’t powered by magic, they’re powered by electricity. If that electricity is produced by fossil fuel sources like coal or natural gas—which together provide nearly three-quarters of U.S. power—our magical cloud may leave a very dirty footprint.

IT-related services now account for 2% of all global carbon emissions, according to a new Greenpeace report. That’s roughly the same as the aviation sector, meaning all those Netflix movies the world is streaming and the Instagram photos they’re posting are the energy equivalent of a fleet of 747s rumbling for takeoff. Unless something is done to green the cloud, we can expect those emissions to grow rapidly—the number of people online is expected to grow by 60% over the next five years, pushed in part by the efforts of companies like Facebook to expand Internet access by any means necessary. The amount of data we’ll be using will almost certainly increase too. Analysts project that data use will triple between 2012 and 2017 to an astounding 121 exabytes, or about 121 billion gigabytes.

“If you aggregated the electricity use by data centers and the networks that connect to our devices, it would rank sixth among all countries,” says Gary Cook, Greenpeace’s international IT analyst and the lead author on its report. “It’s not necessarily bad, but it’s significant, and it will grow.”

The good news is that a number of major Internet companies have begun taking big steps to green their cloud. Greenpeace points to Apple as an industry leader, as the company has committed to powering its iCloud exclusively through renewable energy. It’s backed that up by building the country’s largest privately-owned solar farms at its North Carolina data centers and by powering its new Nevada data centers with geothermal and solar energy. Apple has also purchased wind energy for its Oregon and California data centers.

Facebook is another success story. The company came under criticism from Greenpeace and other environmental groups for depending on coal for more than half its energy, which prompted a global Unfriend Coal campaign. Those protests yielded results—Facebook now prefers renewable energy to power its growing fleet of data centers. Its newest center will be in Iowa, where it has agreed to purchase 100% wind power—a move than pushed the local energy utility to make the single largest purchase of wind turbines in the world.

Facebook’s evolution is a welcome sign that Internet companies are becoming more aware of their environmental footprint. It also underscores the fact that their decisions on how to power their data centers can influence utilities for the better. “Apple and Facebook show the power IT companies have on this stuff,” says Cook.

But there are still major laggards in the industry. Greenpeace points at Twitter, which just went public last year. Unlike Facebook or Apple, Twitter still hasn’t built any data centers of its own, instead renting server space from third party companies. Twitter has remained silent about the kind of electricity that powers its services, while providing very little information in general about its energy use or its energy goals. While some of that silence can be explained by the fact that the company doesn’t own its own data centers, the Greenpeace report points out that other companies that rent servers, like Salesforce and Box, have made commitments to 100% renewable energy.

In response to the report, a Twitter spokesperson said:

Twitter believes strongly in energy efficiency and optimization of resources for minimal environmental impact. As we build out our infrastructure, we continue to strive for even greater efficiency of operations.

As a relatively new public company, Twitter will likely come under more pressure to be transparent about its energy use and environmental goals. The fact that Twitter is so popular among journalists and activists will certainly increase that pressure over time, as happened with Facebook.

But a bigger problem for a green cloud is Amazon Web Services (AWS), Amazon’s highly popular cloud-computing platform. AWS hosts Amazon’s own cloud content, like the Amazon Prime streaming video service, but it also hosts data from countless other customers — including Netflix, which by itself accounts for nearly a third of Internet traffic in North America during peak evening hours. Amazon has been mostly silent about the environmental footprint of its cloud services, though the company claims to have very high utilization rates, which allow it use cheaper off-peak electricity—but again, there’s little open data on this. The company’s data centers in northern Virginia are by far its largest, but just a tiny sliver of the electricity there is provided by renewable sources, with the bulk coming from coal. AWS does say that its data centers in Oregon (which includes the company’s YouGov platform) are run by 100% carbon-free power, but it’s not clear how those power sources break down, and Amazon hasn’t publicly committed to using renewable energy.

When asked about Greenpeace’s report, an AWS spokesperson said the company agreed that efficiency and clean energy were important for cloud computing, but also said the report “misses the mark by using false assumptions on AWS operations and inaccurate data on AWS energy consumption. We provided this feedback to Greenpeace prior to publishing their report.” Greenpeace’s David Pomerantz, a co-author on the report, said that AWS declined to share data on energy consumption before the report was put together, unlike a number of other companies:

We did share our data with Amazon in advance of publishing the report. Amazon told us that our energy mix data for some of its AWS facilities was incorrect, but refused to offer alternative data for any of its facility other than Ireland, where it claimed a mix of 50% renewable energy and 22% coal. When asked, Amazon refused to provide data on how it is achieving that mix in Ireland, so Greenpeace has continued to use Irish national data for that facility. Using Amazon’s Ireland data would result in a company CEI [Clean Energy Index] that would be improved from 15 to 19%, still quite low.

Amazon has noted in the past that cloud computing is inherently more efficient than traditional computing, since companies are able to consolidate their data center use. And moving media and other services as data via the cloud is much more efficient than creating and shipping physical objects. But the cloud doesn’t come free. As more of our lives migrate to the digital ether, Internet companies—and their billions of customers—need to be more aware of the power behind the cloud.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com