Exactly a century ago this Friday, on the morning of Feb. 24, 1917, the office of U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing received a telegram of warning from the U.S. Ambassador to Britain. In roughly three hours, the ambassador wrote, he would send another telegram, meant for Lansing and President Woodrow Wilson.

It was going to be something important.

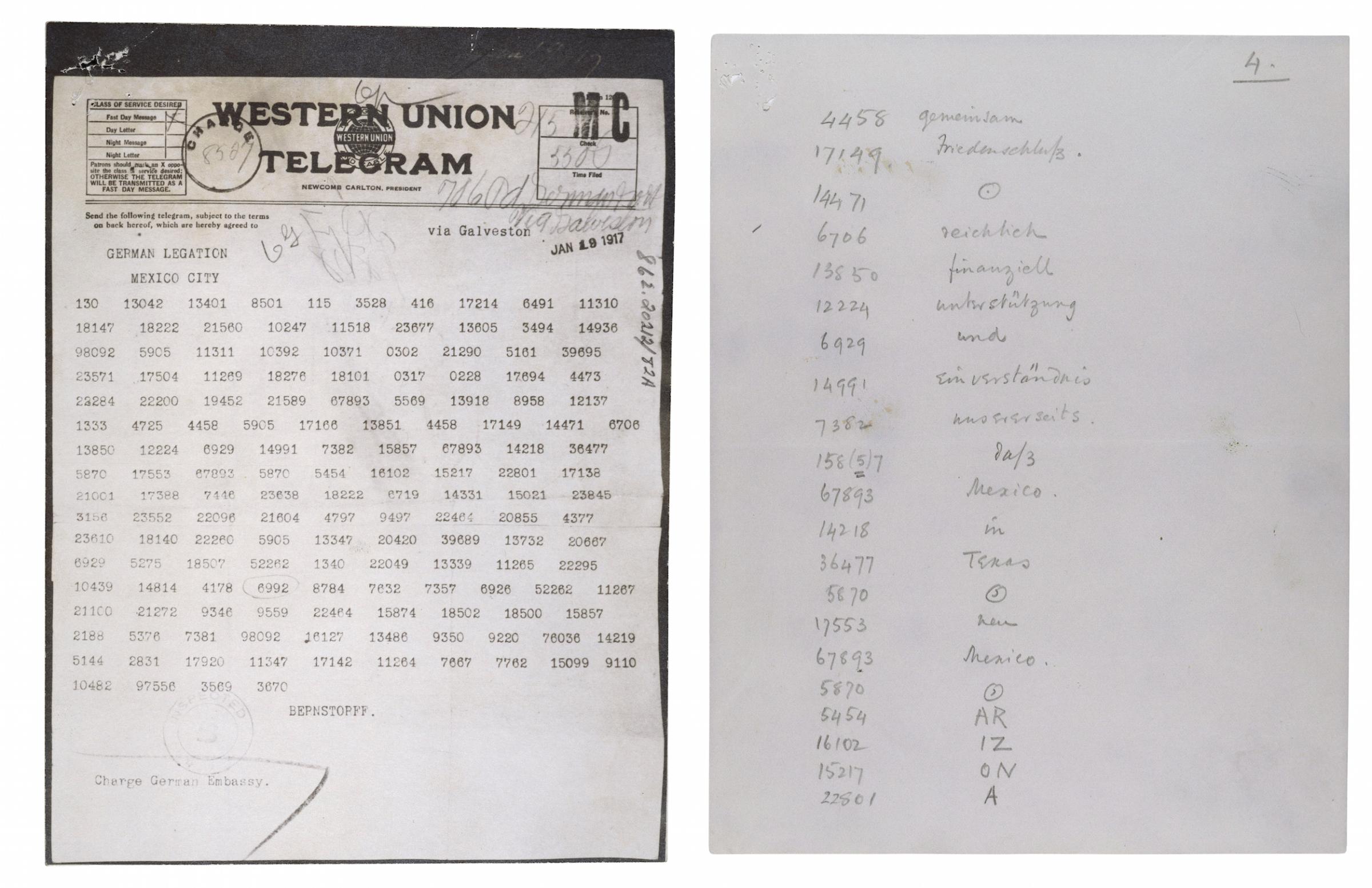

When the second telegram arrived, it bore news that would play a role in changing the course of the next 100 years: the ambassador was telling the U.S. that he had received from the British the decoded text of a message they had intercepted from the Foreign Minister of Germany, Arthur Zimmermann, to his country’s minister to Mexico.

At the time, the U.S. remained neutral as the Great War raged across Europe. Although many Americans saw it becoming inevitable that their nation would eventually join the fight, those who favored staying out of it could still make an argument that what was going on was none of America’s business. After all, an ocean separated the U.S. from the fighting and, though attacks by German submarines on ships making the Atlantic crossing had earlier galvanized those who favored war, German authorities had agreed in 1916 to limit attacks on non-military ships.

But the information in the telegram intercepted by the British told the President that the time had come.

“Among the official cryptograms which have been intercepted and translated by governmental authorities other than those for whom they were intended, the most important of all time, either in war or peace, is undoubtedly the one deciphered by the British Naval Intelligence which is known to historians as the Zimmermann telegram,” declared a 1938 War Department report, which has since been declassified.

The chilling text of the document, as transcribed in the National Archives, was as follows:

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal or alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President’s attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace. Signed, ZIMMERMANN.

Though the War Department report acknowledged — as is still the case — that experts may disagree over whether the telegram actually pushed the U.S. toward anything that wouldn’t have happened for other reasons, this telegram is generally seen as a key step in the United States’ move toward deciding to join in on World War I.

After all, at the month’s end, the Associated Press alerted the nation to the fact of the telegram, explaining that President Wilson had already been in possession of the document as German officials protested that they wanted to maintain friendly relations between the two nations. After that, it would be hard to argue that the U.S. could maintain neutrality in the conflict that had already been tearing Europe apart for years.

The declaration of war would come in April.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com