“There’s no such thing as an impossible picture. If you can visualize a picture in your mind, you can make the camera do it.” – John G. Zimmerman

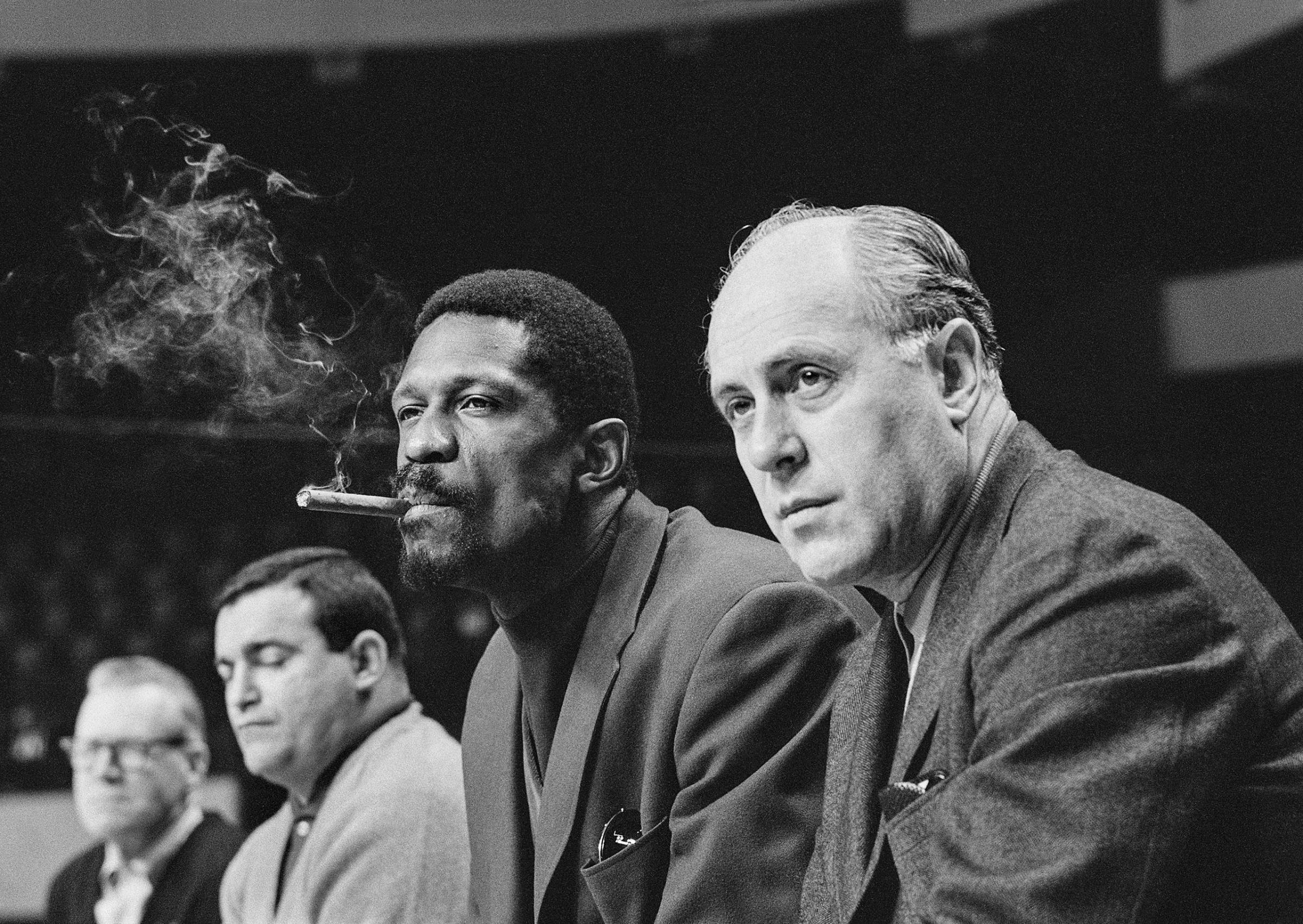

Many know the work of John G. Zimmerman in the context of his groundbreaking sports photography. He was the first photographer to place the camera above a basketball hoop and was known for using his equipment in new and innovative ways to get the shot he wanted. He was among the first staff photographers for Sports Illustrated, photographing 10 Olympics and many covers for the famous SI Swimsuit Issue.

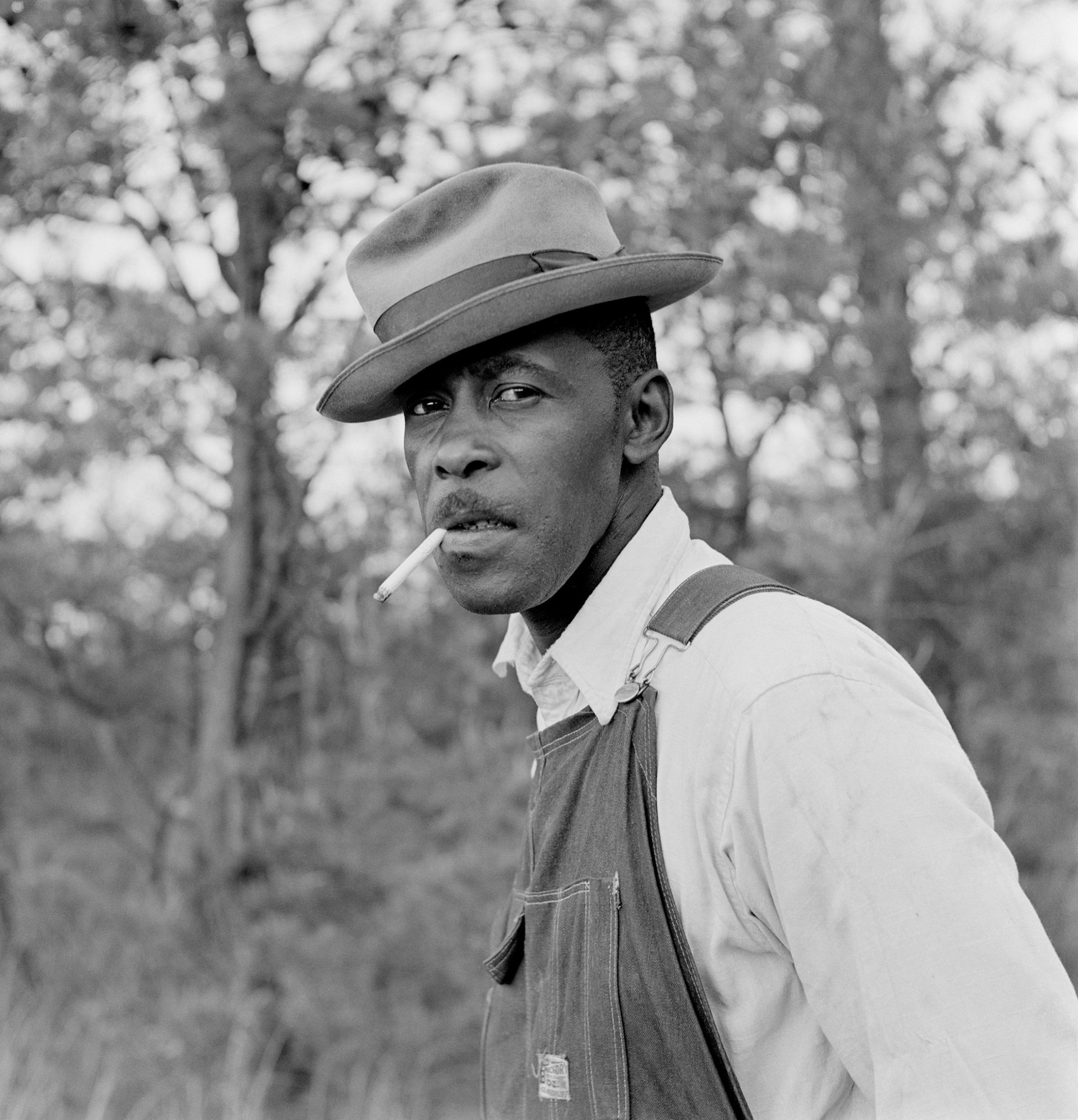

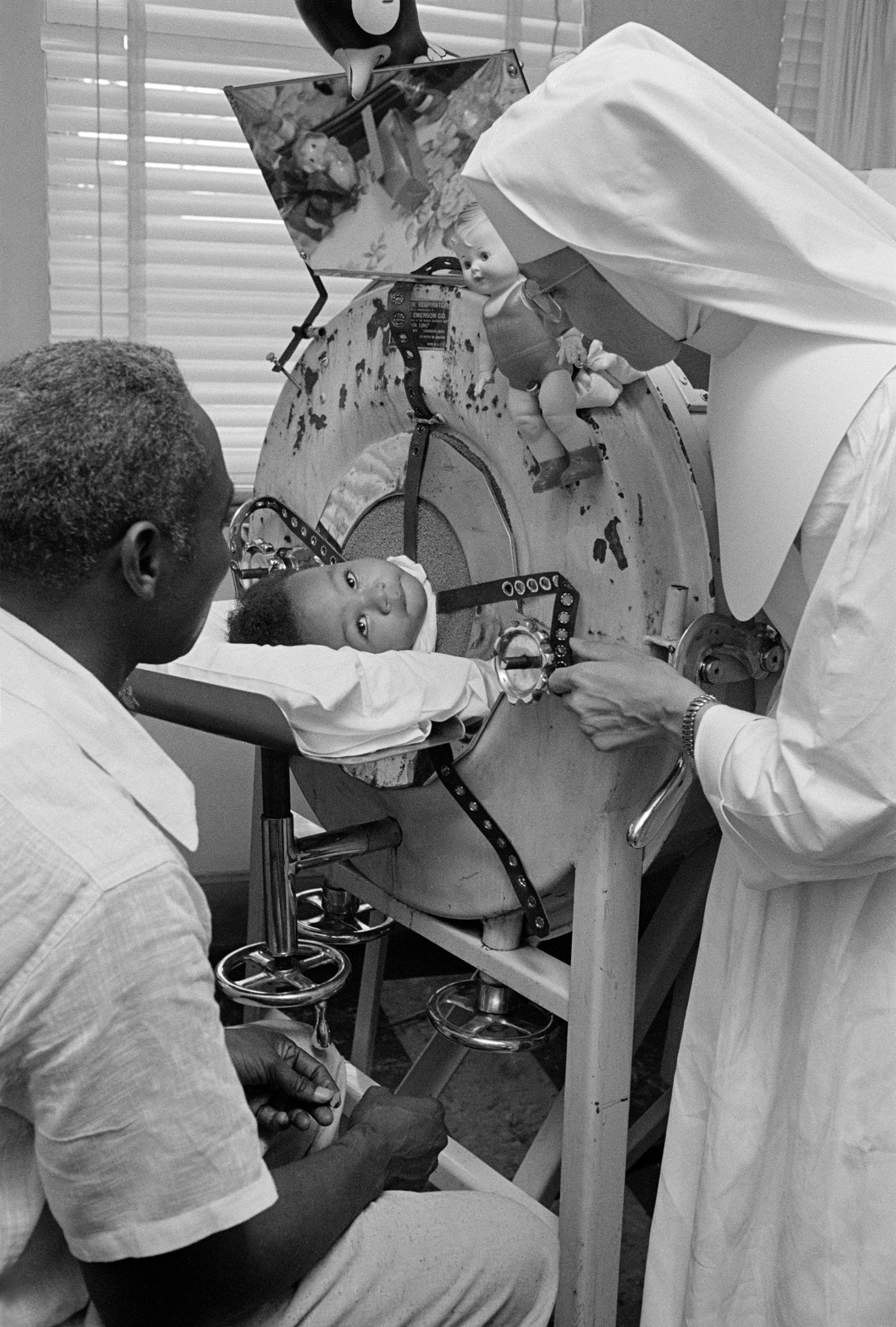

But, as the new book America in Black and White illustrates, his archive goes much deeper than that. The book (like its companion exhibit) offers a new look at Zimmerman’s early humanist photography, focusing on his career between 1950 and 1975, including famous pictures like the Mariner Church relocation (slide 7 above) as well as images shot for LIFE and Ebony in their coverage of the Jim Crow South. Many of the images — which were selected by Belgian scholar Arne De Winde with the input of Zimmerman’s family — have never been seen or published before, and they show a thoughtful eye and attention to detail that would later inform his sports photos.

His career in photography began at Freemont High School in California, where Hollywood cinematographer C.A. Bach led a photo program that produced no fewer than 8 LIFE staff photographers, including John Dominis, George Strock and Mark Kauffman. His professional career was jumpstarted when he happened to capture an attempted assassination of President Truman, the photos of which would be published in both TIME and LIFE in 1950.

One of the rarer stories in the book shows a shoeshine contest in Wilson, N.C., in 1952. Speaking with TIME, Zimmerman’s daughter Linda recalled getting this set from the TIME-LIFE archives with little information on what she was seeing. Because the story had not been published, the magazine had not collected extensive caption issue. Intrigued by the subject matter, she worked with local librarians and archivists in North Carolina over the course of several years to identify and locate the winner of the contest, Curtis Phillips.

Zimmerman’s early assignments in the 1950s for Ebony, photographing the segregated south, clearly influenced the way he would photograph in the years to come — and this look behind the scenes makes clear the pervasive reach of that time. For example, the fifth photograph above, showing a young African-American girl receiving polio treatment in Montgomery, Ala., was not published. But a similar Zimmerman photo of a young white girl ran in TIME magazine in 1953.

Linda Zimmerman notes that her father, who died in 2002, always worked in a linear fashion, always looking ahead, so the book’s focus on his early work is “a wonderful surprise” that contextualizes his entire career and offers a look at work rarely seen.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com