This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

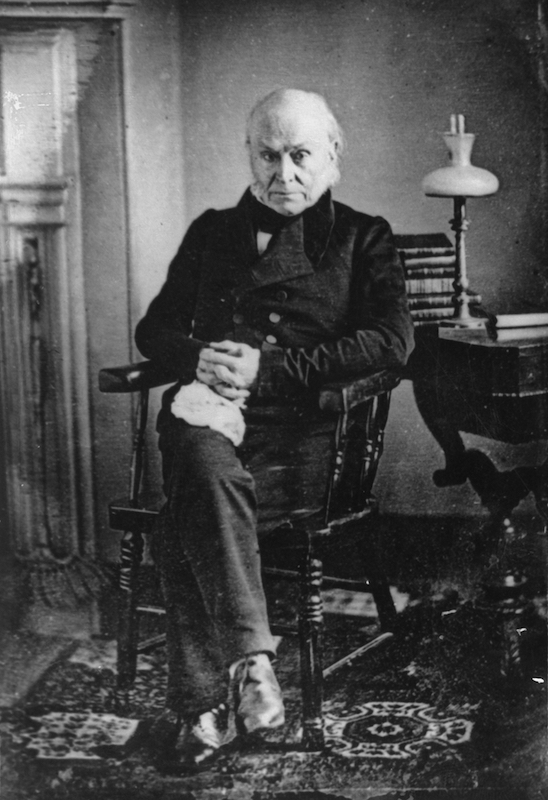

What presidents do after they leave office is a relatively underrated part of the crafting of presidents’ long-term image. As President Obama contemplates his next moves and historians start contemplating his legacy, the complicated path John Quincy Adams took to becoming America’s best ex-president is worth considering. Those who have a general knowledge that former president Adams became an antislavery hero in Congress may find it surprising and instructive to know that he did not simply or immediately morph into “Old Man Eloquent” against the Slave Power.

Unlike Barack Obama but very much like Jimmy Carter, Adams left office after one term and found himself widely regarded as a failed president. During his term of office between 1825 and 1829, opponents in Congress coalescing as the Jacksonian Democrats repeatedly foiled his domestic agenda and even his foreign policy goals. Adams came to office, for instance, announcing a bold program of government support for internal improvements (what we call infrastructure), and education. He also wanted to lead a campaign of moral reform.

Building on years of attacks in Congress against federal government spending, Jacksonians revolted against the exercise of federal power and Adams’s emphasis on “Improvement.” We are used to presidents being gridlocked on the domestic front and having a freer hand in foreign affairs, but the Democrats, led by southern planters, were even able to effectively stymie Adams’s proposal to send a United States representative to a conference of newly independent – and slave-emancipating – Latin American republics.

Adams proved insufficiently shrewd in his use of the patronage and other political weapons at his disposal to counter the Democratic opposition. Like President Obama, he wanted to rise above attacks in the press that had characterized the long campaign of 1824. As a man who had left the Federalists because of their sectionalism during the Jefferson administration, and as son of a president who had felt betrayed by the same party, he thought he was destined to dial down the partisanship that had stymied legislation and warped national debate on key issues. But the idea that he came to power in early 1825 by means of a “Corrupt Bargain” with Henry Clay, and unfortunate if telling phrases while president such as urging Congressmen not to be “palsied by the will of their constituents” from supporting his Improvement measures, sealed Adams’s image as out of touch with the ever more assertive “Common (white) Man” for whom Jackson claimed to speak. The result was a decisive Jackson victory in the election of 1828.

When Adams left office in March 1829, it was by no means clear to him what he would do next or the stances he would take on public issues. On no issue was he more uncertain than slavery and the complex sectional politics brewing around it. His post-presidential writing projects, including a “History of Parties in the United States,” ruminated on that problem, which he had avoided while Secretary of State and President. One primary thrust of this analysis was that “the lurking jealousies of slave-holders” against the free states had culminated after 1825, when those slaveholders had worked “to ruin the reputation and paralyze the power of” his presidency. But much as he had tried to govern the United States as the president of the entire Union, he kept such thoughts to himself in the immediate aftermath of his reelection defeat. Adams kept in contact with multiple active national politicians, but strongly believed that his still tarnished reputation made it impossible for him to play a constructive public role in national politics.

Only in 1831 did Adams reemerge on the national stage, in response to hot-button issues such as sectionalism and slavery. South Carolina’s ongoing drive to nullify the federal tariff prompted Adams to give a blistering and highly publicized July Fourth oration in Boston opposing this extreme form of Southern sectionalism and vindicating the binding power of the Union. That same year Adams began his first term in the House of Representatives.

Fully aware that an ex-president taking up such a position in Congress was unprecedented, he was by no means sure of the course he would take. Over his 17-year career in Congress it became clear that some of what had kept him from being an effective president would make him an excellent Congressman. He took stands against Jackson’s Indian Removal policy, nullification, and eventually (and most famously) the Gag Rule banning antislavery petitions. But his carefully cultivated reputation as a man of principle rather than a partisan hack earned him the respect of the vast majority of his fellow Congressmen, as manifested by his appointment to important committee chairmanships. On some issues he played a nonpartisan, leading role. Both Northerners and Southerners, Democrats and National Republicans, argued that Adams must keep his chairmanship of the important Committee on Manufactures because he “had it eminently in his power, by his peculiar” position as a revered statesman, “to give repose to those angry passions which now shake the public mind.” He was, they gushed, “the only man in the Union capable of taking the high stand of umpire.” The idea of John Quincy Adams as glue for the Union was far from his image after 1836, and must have come as a surprise to him after the tumult of his presidency. But it would have been a pleasant surprise to someone who nurtured not only a love for the Union but also a healthy ego.

The darker side of the making of Adams into an antislavery hero in Congress had a lot to do with the exceptions to that rule of peer respect. As during his presidency, it was Southern representatives who menaced Union and improvement, in the process helping to raise up one of their most effective Congressional opponents. This Southern hostility to the Union and improvement, coupled with perceived insults to Adams’s constituents, came together in early February 1833 and called forth his first real antislavery expression in the House. On February 1, Adams took umbrage at Richard Henry Wilde motion not to receive resolutions on the tariff from the Massachusetts legislature. Adams branded this latest motion to table rather than hear Northern expressions of opinion – from a state legislature, no less – “an insult to the State of Massachusetts” that was also just the latest attempt by a Southerner – Wilde was from Georgia – to silence Northerners’ free speech on a vital issue. The business on February 4 began with a small skirmish that would only confirm Adams in his opinion that Southerners were domineering. That day Southerners moved to table rather than hear petitions for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. Adams, though “not in favor of the sentiments expressed in the memorial, was opposed to laying it on the table, as being disrespectful to the petitioners” and hostile to a right “guarantied by the constitution.” For the first time, the reader of a public source – the Congressional Record (as opposed to his very revealing diary) – can sense that Adams was ready to explode in an antislavery direction given that his personal opposition to slavery and hostility to slaveholders’ power had come into alignment with his solicitude for the constitutional Union and preference for bold leadership.

So by 1833, John Quincy Adams had found his future path as Congressional scourge to the Slave Power. But it is worth noting how long it took him to find and enter that path. For those disposed to administer tests on politicians’ and ex-politicians’ purity of motives, it may also be instructive to note that it was a mixture of antislavery and less noble, or at least more strategic or political, motives that moved Adams in this direction. For those who are looking for creative possibilities in the American political system, it is striking that our supposedly most elitist ex-president found in the more humble precincts of the Congress a path out of the partisan mess that had frustrated him as president.

Matthew Mason is an Associate Professor of History at Brigham Young University, and author of other books including Apostle of Union: A Political Biography of Edward Everett (2016). David Waldstreicher is Distinguished Professor of History at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and author of, among other works, Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification. They are co-authors of John Quincy Adams and the Politics of Slavery (Oxford University Press).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com