When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed his infamous Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942 — a full 75 years ago this Sunday — it created the legal framework for the eventual internment of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans, a shameful episode in American history that would later draw an official apology from the U.S. government.

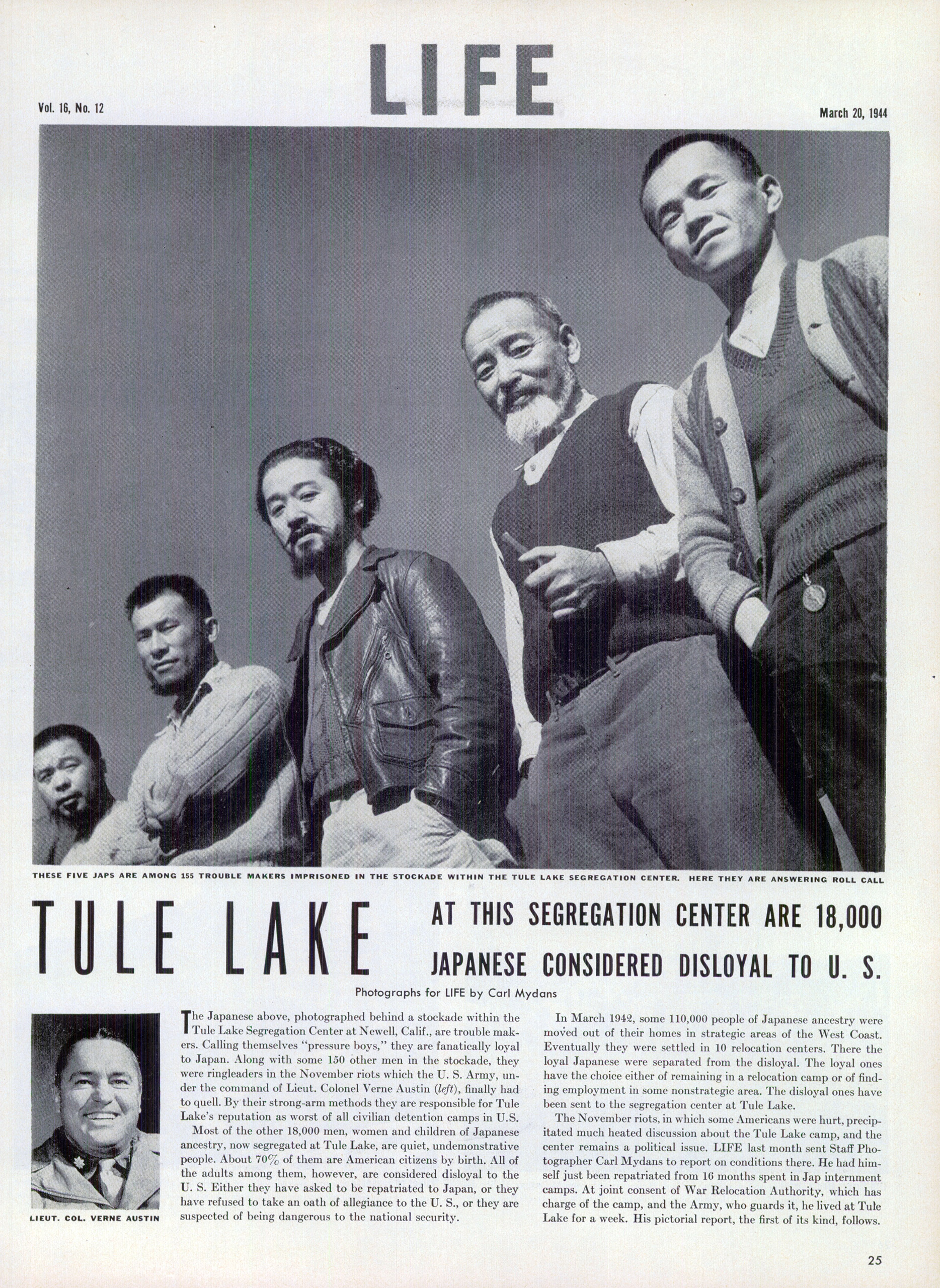

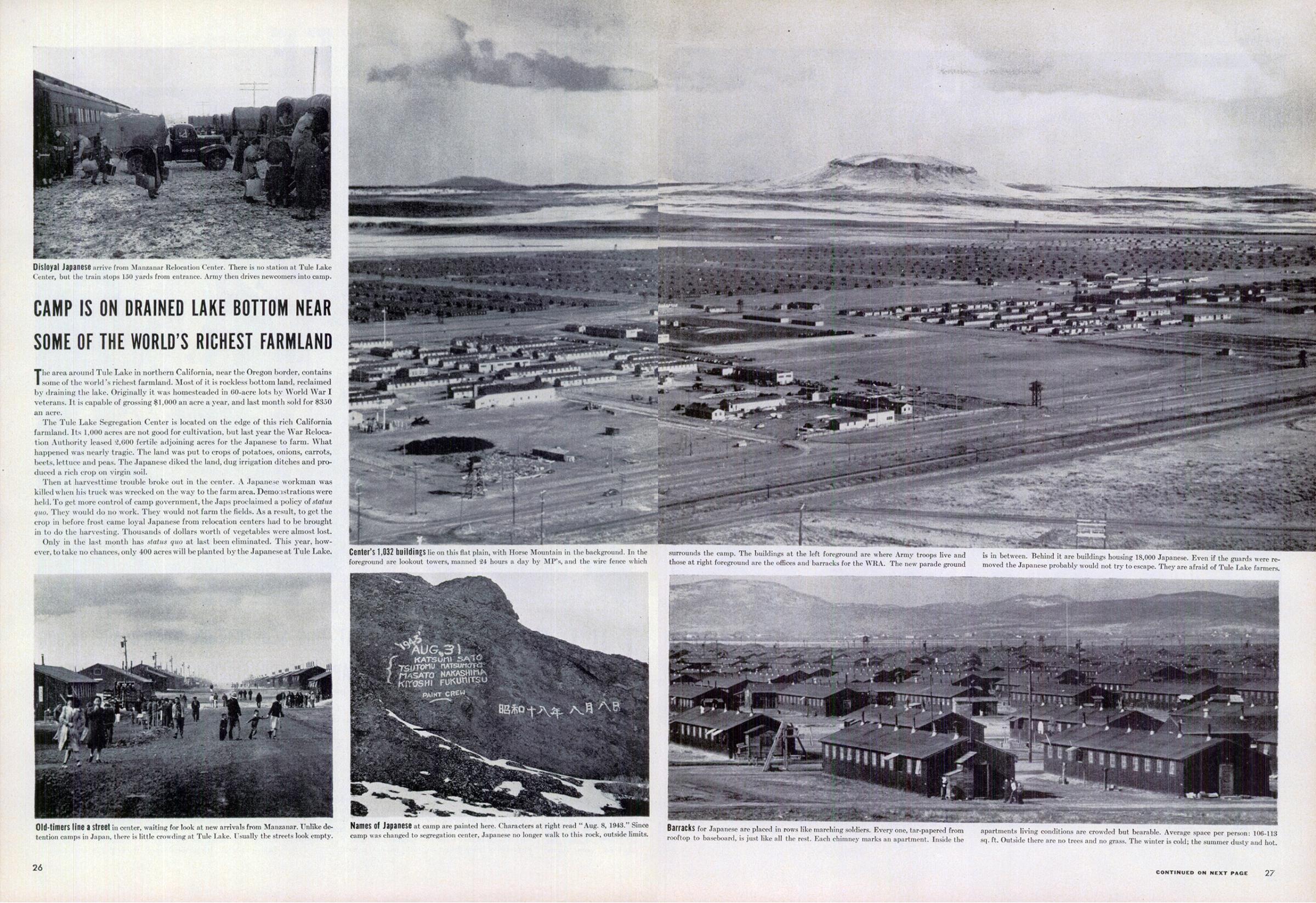

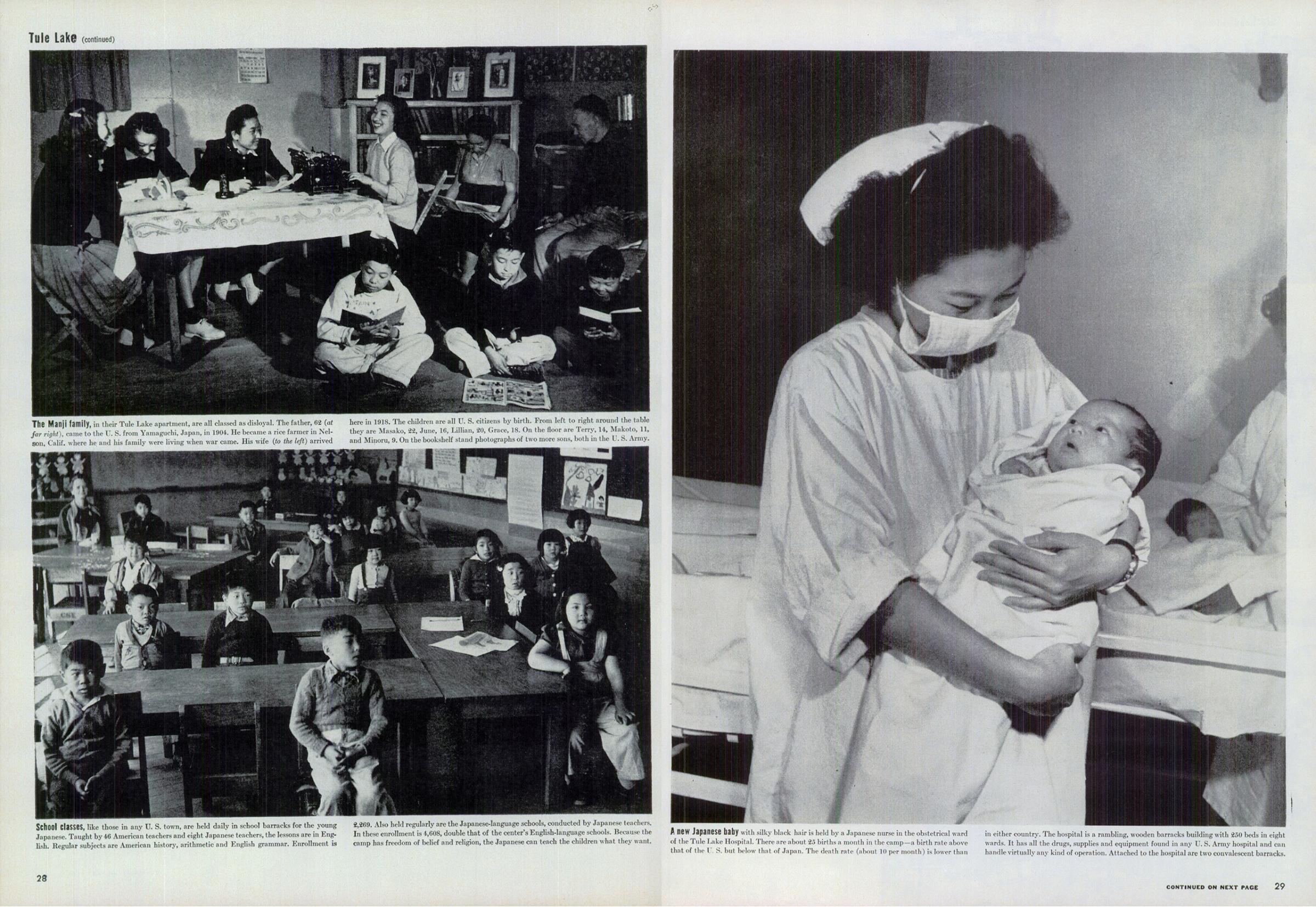

The internment and relocation were not monolithic, as LIFE readers learned from a 1944 report by photographer Carl Mydans. The Japanese-Americans who were deemed to be disloyal or dangerous to the U.S. — though sometimes for no reason beyond suspicion — were set apart from the others, and many of them ended up at a California camp known as Tule Lake Segregation Center — known as the “worst of all civilian detention camps” in the country, per LIFE.

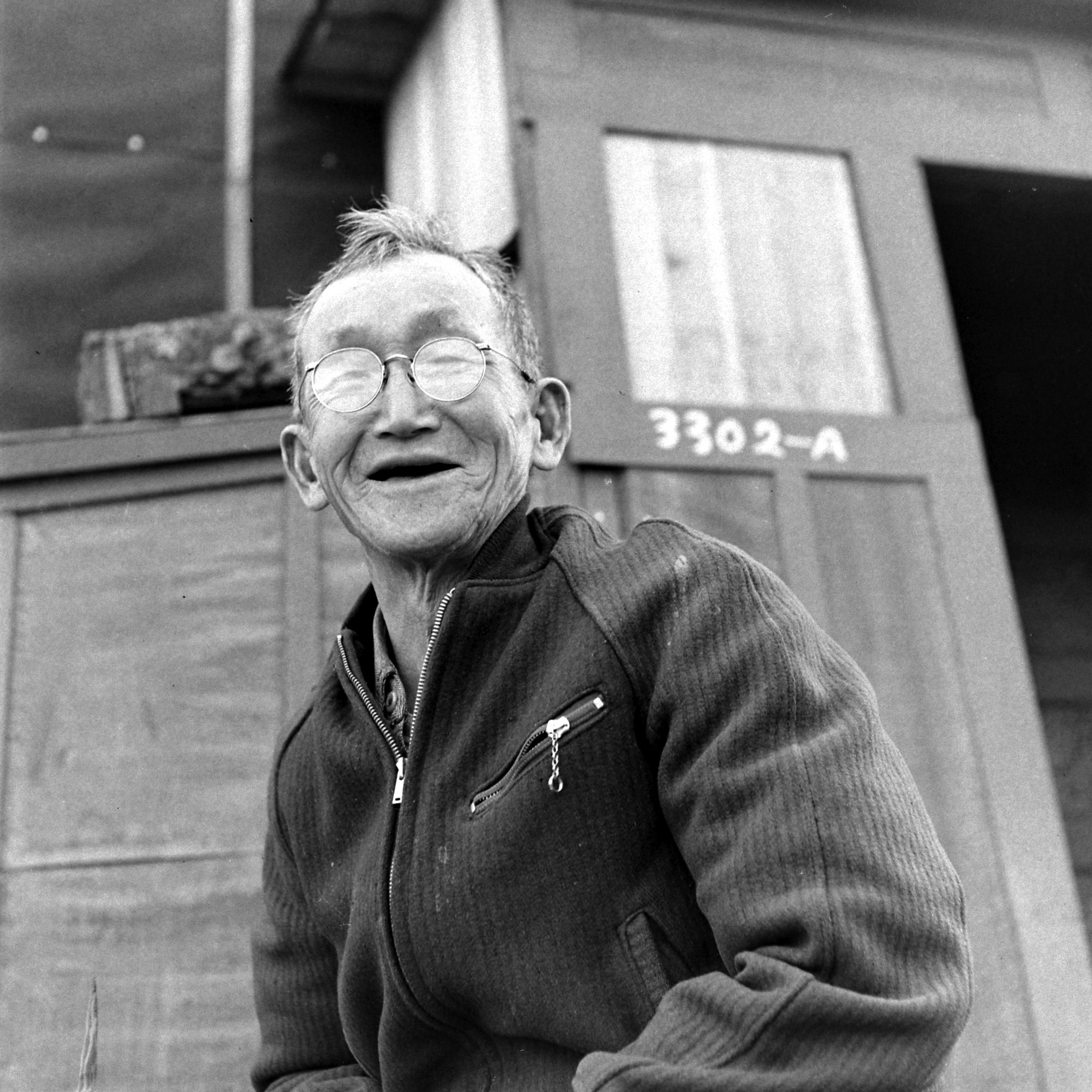

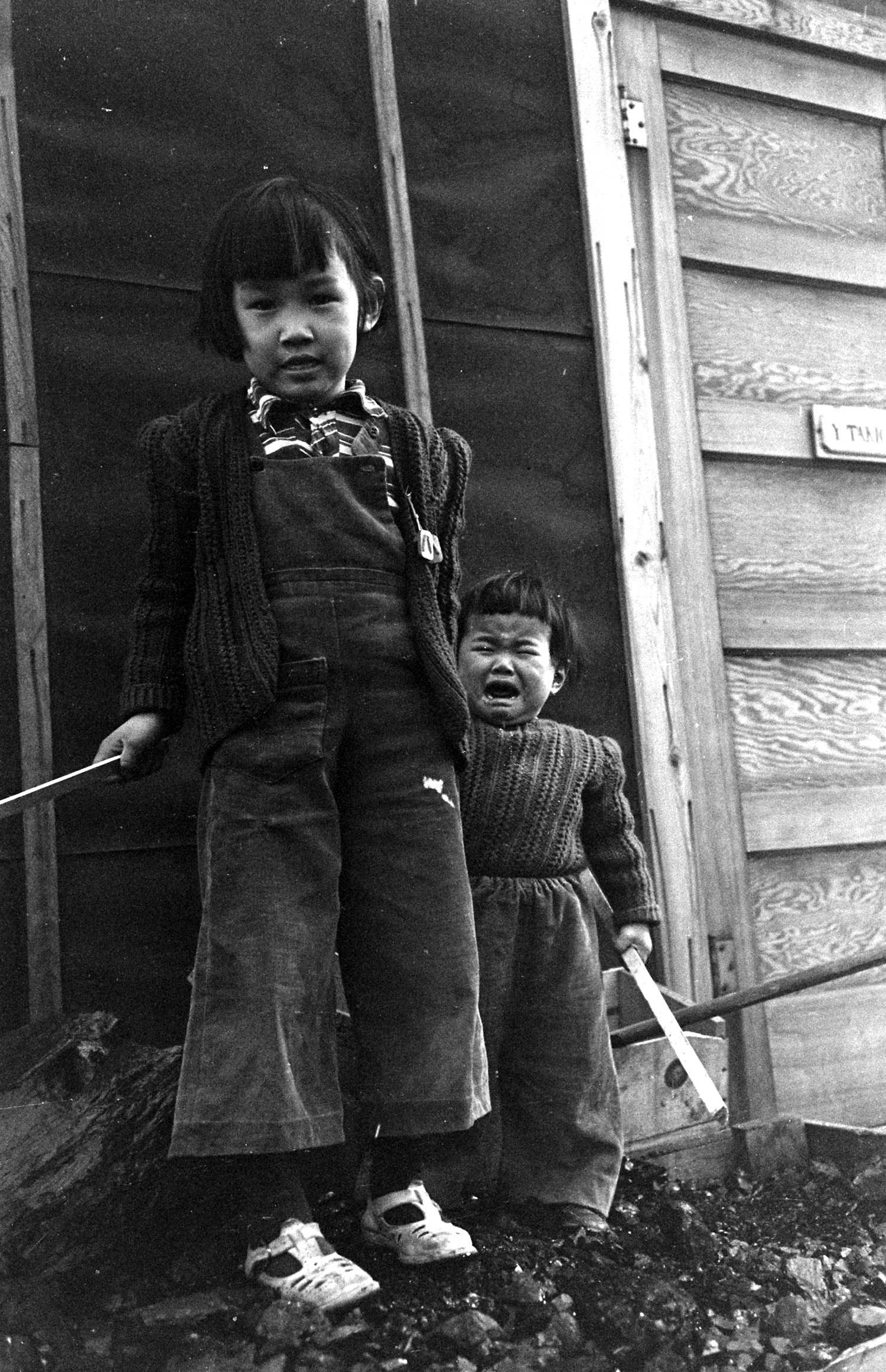

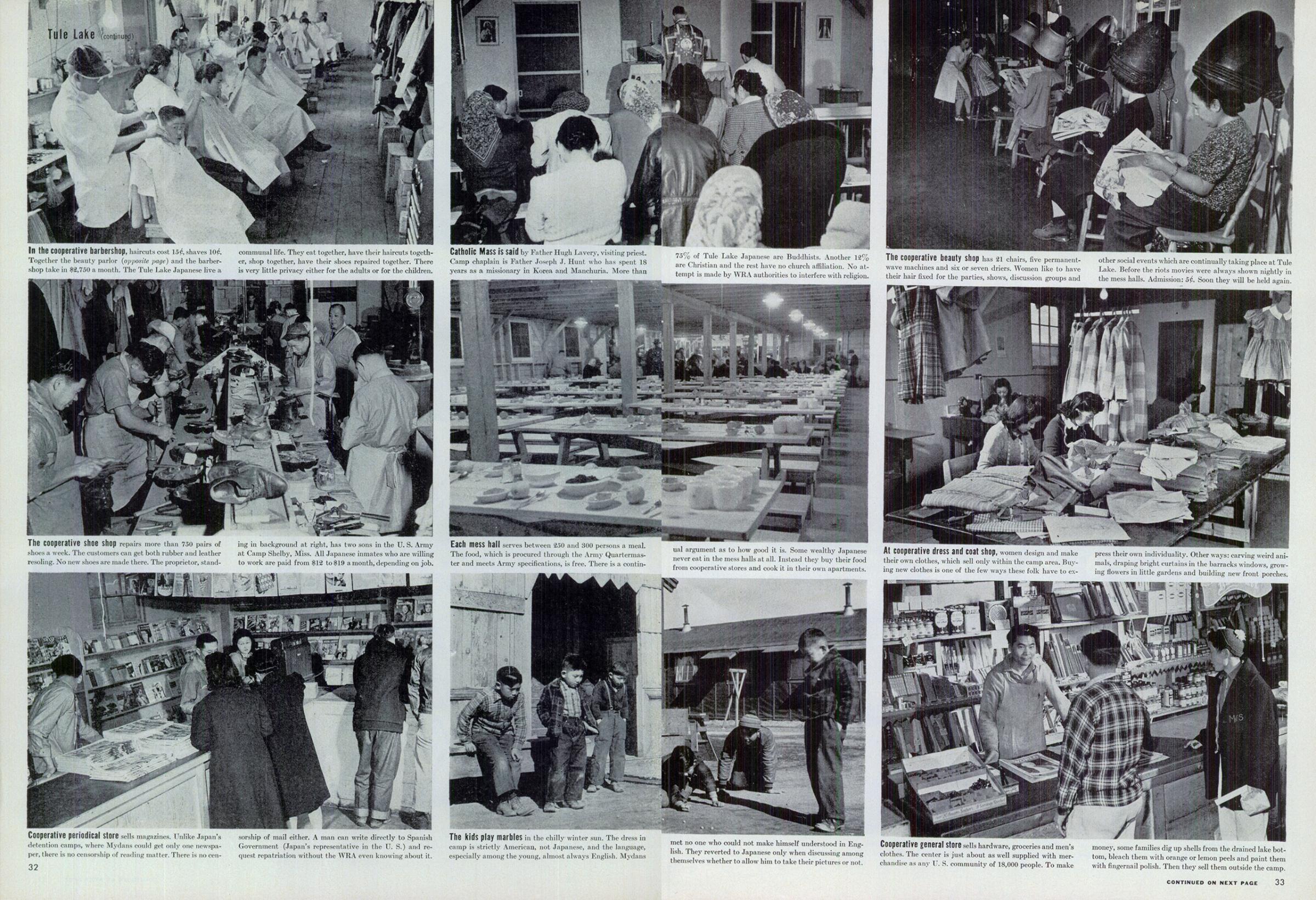

There were about 18,000 people there, including children, and 70% of the prisoners were native-born American citizens.

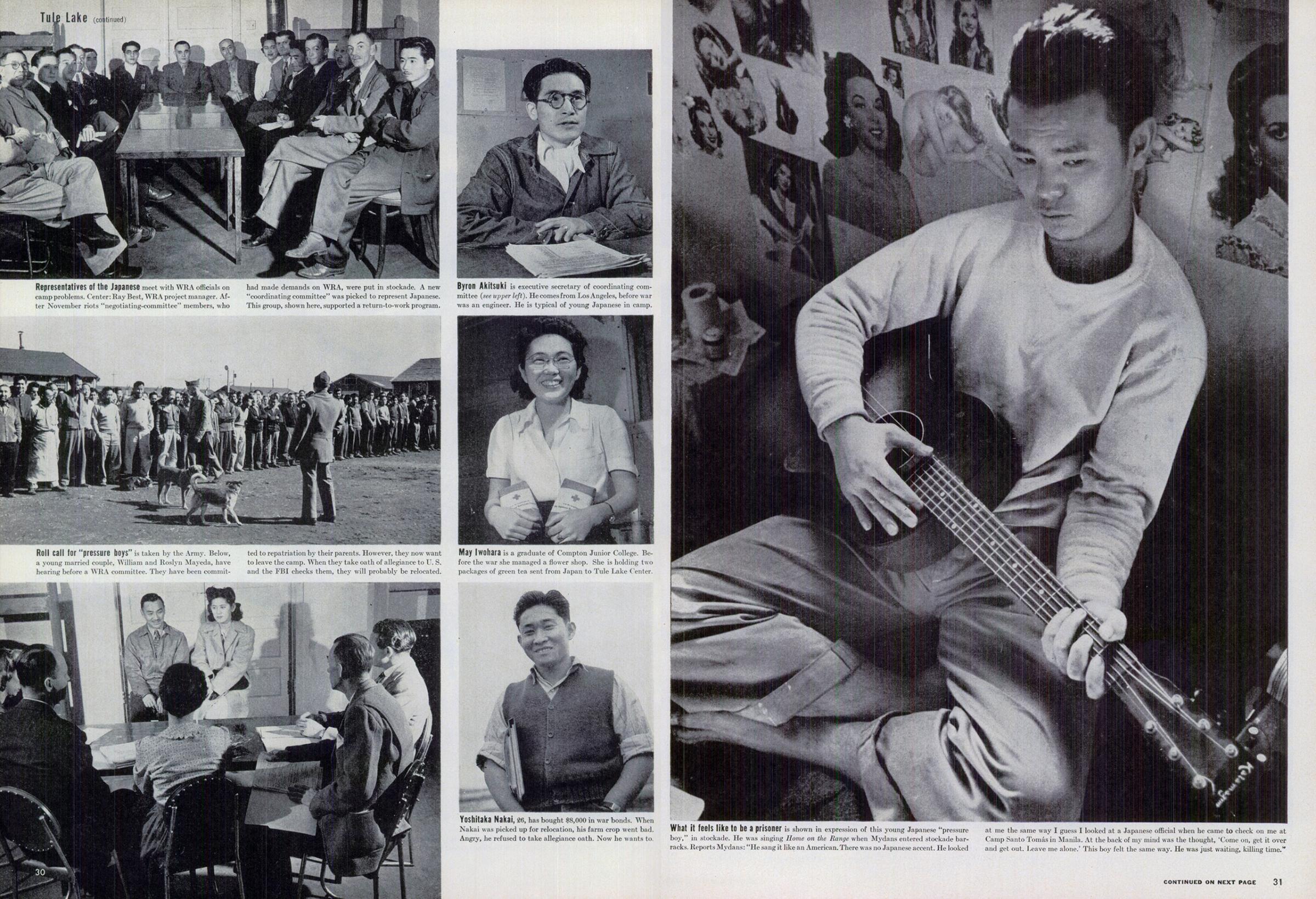

Even in the instances where the reason why someone had been sent there were more concrete, there were often extenuating circumstances: for example, Mydans photographed one man who had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the U.S. because he had been asked to do so right after his being picked up for relocation had resulted in the harvest at his farm rotting. When his anger passed, he was ready to take the oath, but by that point he was already at Tule Lake. (Interestingly, Mydans had a point of comparison for the camp: he himself had spent time in an internment camp in Asia, after Japan seized the Philippines while he and his wife were reporting from there.)

LIFE visited the camp shortly after an uprising at the camp had prompted a crackdown from the military officials running the place. Even at the time, it was acknowledged by many that the way the Army handled the event was counterproductive and harmful, and that Japanese-Americans loyal to the U.S. suffered the consequences of the actions of others.

As TIME would put it in 1961, “the Army’s Military Police took over the camp, manned the watchtowers and began patrolling the area with Jeeps and command cars. The transition to Nazi-type stalags was complete.”

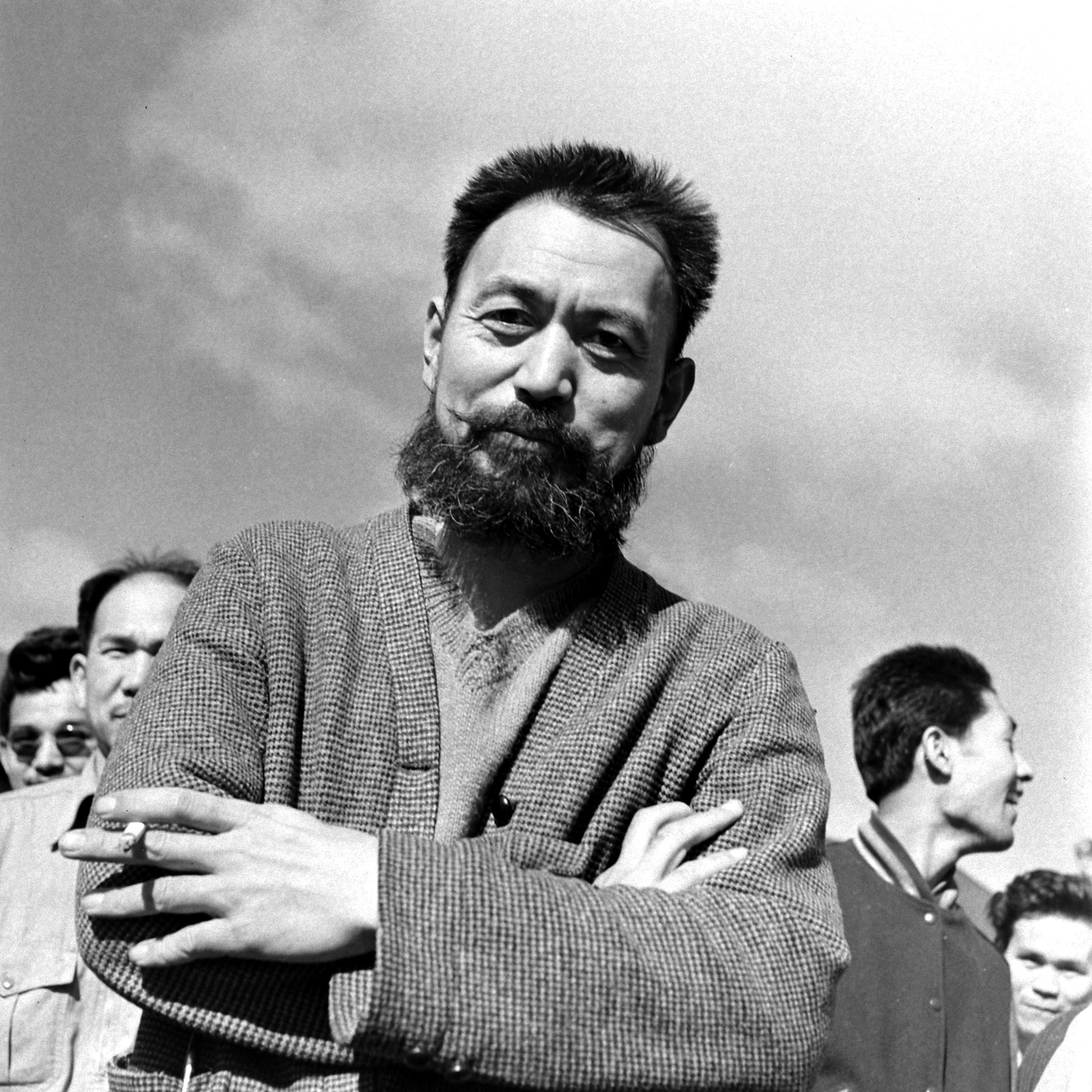

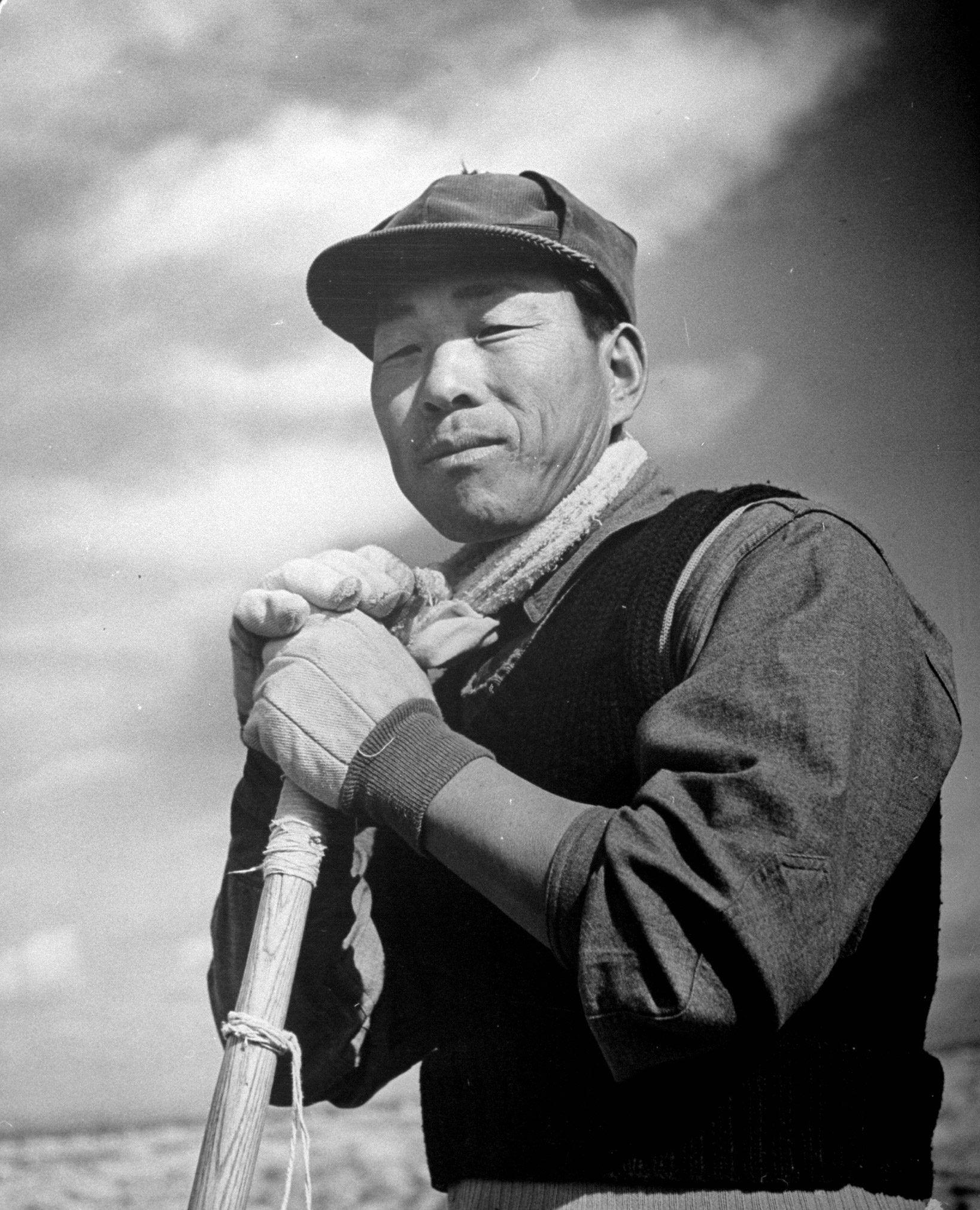

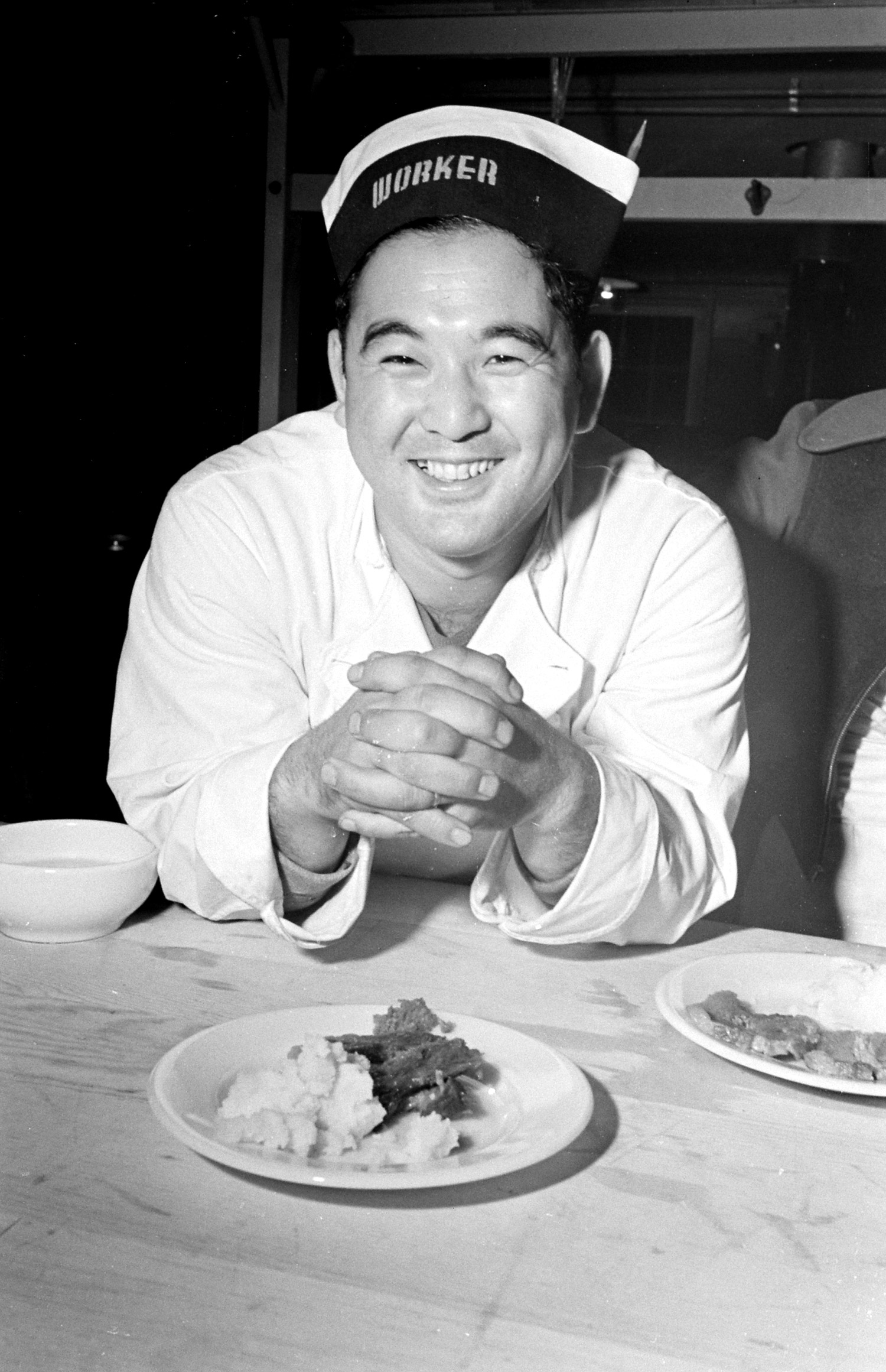

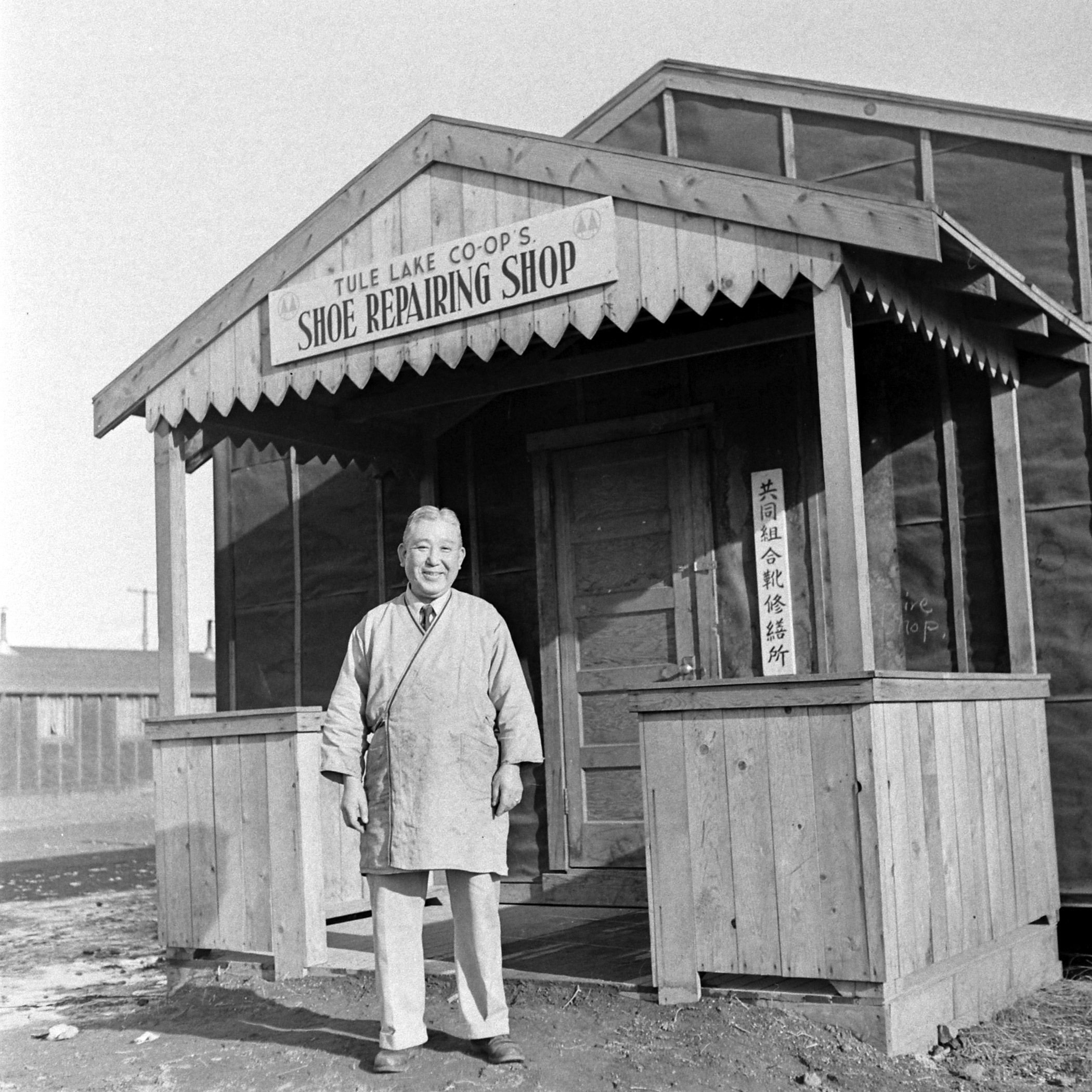

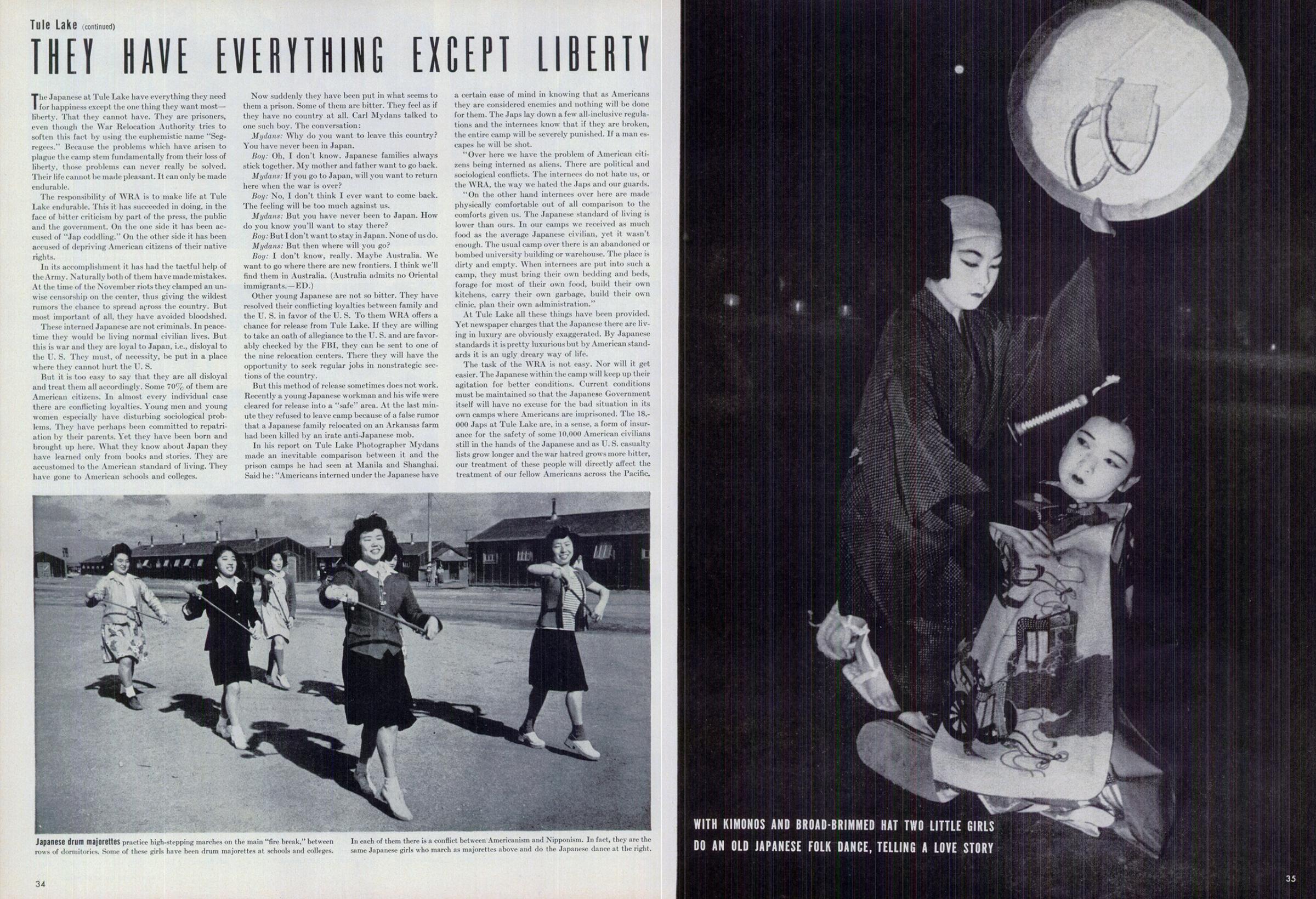

The portraits seen above, which were not published by LIFE when the story ran, in the Mar. 20, 1944, issue, help illustrate the wide range of people who were made to live under military rule at Tule Lake: women, men, children, the elderly, farmers and professionals.

The “segregees” at the Tule Lake camp, as Mydans saw it, “have everything they need for happiness except the one thing they want most—liberty.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com