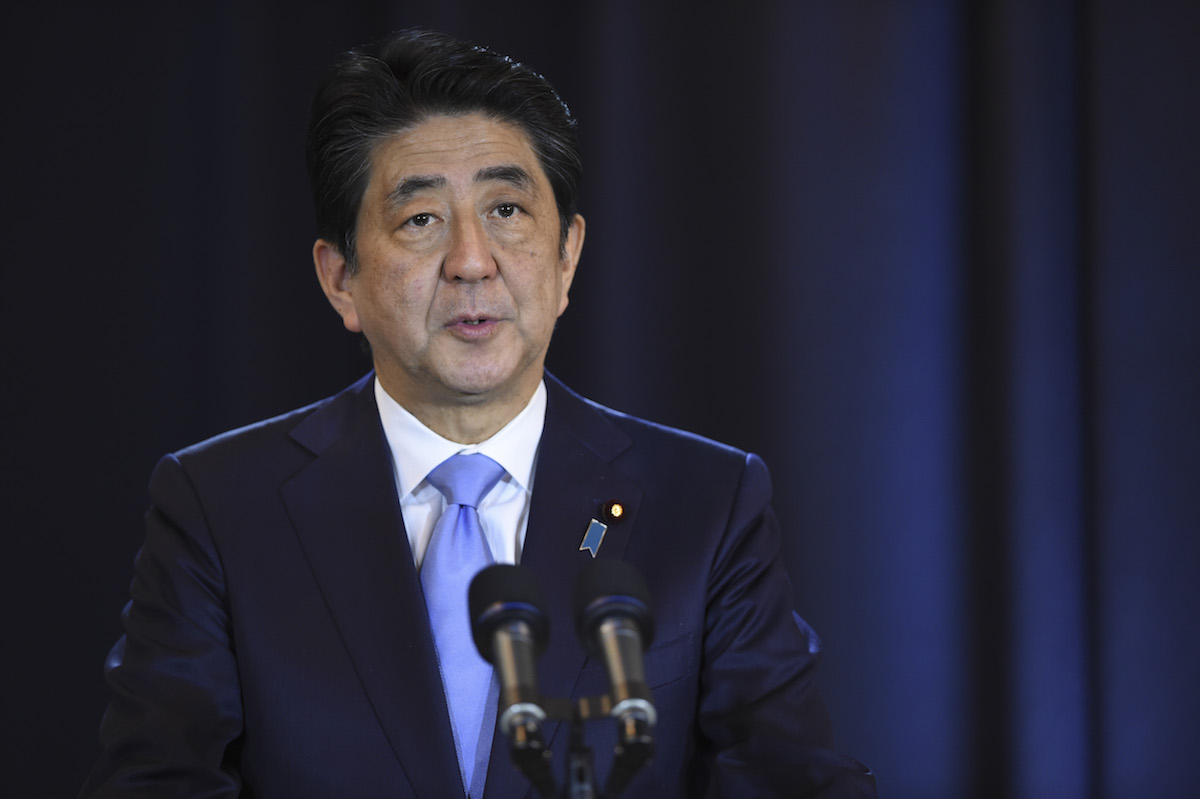

When President Obama and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe meet in Honolulu Tuesday and pay a visit to the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor, the trip will mark one of the first visits by a sitting Japanese leader to the location famous as the site of the 1941 Japanese attack that ultimately provoked the U.S. to enter World War II. “The two leaders’ visit will showcase the power of reconciliation that has turned former adversaries into the closest of allies,” the White House said in a statement.

Just as was the case when Obama visited Hiroshima earlier in the year—as the first sitting U.S. President to go to the site of the atomic bombing—the visit by Abe comes after many years of debate in the U.S., Japan and elsewhere about how the two nations should come to terms with the legacy of World War II.

In 1991, when the world marked the 50th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, TIME examined the way Japan talked—or failed to talk—about the attack and the rest of World War II, in an article by Barry Hillenbrand and James Walsh. “Americans remember Dec. 7 as a day of infamy. Japanese, when they think of Dec. 8 at all, tend to dismiss the date as mizu ni nagasu: water under the bridge,” the article noted. Many people found that stance problematic:

…[For] many nations, what remains troubling about Japan is a sense that its economic engines are escaping history at full steam. They fear that the lessons of Pearl Harbor and the other traumas that attended Japanese militarism have never been squarely faced, let alone digested.

All nations embroider their history to some extent. In Hungary schoolchildren are taught that Attila the Hun, hardly history’s most sympathetic character, introduced uplifting elements of Roman culture to his court. Britain turned the painful retreat from Dunkirk into a triumph of the spirit. Americans remember the Alamo as a heroic episode, though the war for Texas was a land grab by gringo interlopers. In recent decades Japanese officials, abetted by political and business conservatives, have subtly but systematically diluted the facts about Japanese aggression in Asia from 1931 to 1945. The tampering is reflected in school textbooks and popular literature, films and television, and has rendered some of the war’s tragedies almost benign.

Japan‘s ruthless invasion of China is termed an “advance.” The 1937 rape of Nanking, in which imperial troops massacred thousands of Chinese civilians, is deemed problematic because of “muddled factual data.” Other harsh episodes like the Bataan death march are wholly ignored, perhaps in hopes that dodging the unpleasant will somehow make it disappear. But the bitter memories will not go away, and Japan is too pivotal and wealthy a global power to be allowed—or to allow itself—the luxury of historical amnesia. Increasingly, Asian neighbors demand that it deal more forthrightly with its past, especially if it hopes to play a leading regional role. Many Japanese scholars, exasperated by Tokyo’s studied forgetfulness, are joining foreign critics in insisting on the same thing. “Without a deep understanding of the many facets of the war,” says Makoto Ooka, a prominent poet, “the Japanese people cannot regain their sense of dignity in the world.”

One reason for that situation, suggested the president of Tokyo Women’s University at the time, was that a century of movement toward modernization in Japan had discouraged any culture of reflecting on the past. As an example of that stance, Walsh and Hillenbrand cite the response of an unnamed official, on the subject of Pearl Harbor’s anniversary: “It’s a historical fact. We can’t deny it, but let’s move on.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

At the time, the relationship between the U.S. and Japan was a tense one, for very different reasons than had been the case a half-century before. Though surveys showed that a majority of Japanese people admired the U.S., much ink was spilled over the idea that a rising tide of anti-Americanism was about to sweep the nation. Meanwhile, American politicians and consumers alike fretted over competition with the growing Japanese economy and disagreement over Japan’s response to American military efforts in the Persian Gulf.

But, when it came to acknowledging the past, things were already beginning to change: that year, while marking the anniversary of the atomic bombing of his city, Hiroshima’s mayor Takashi Hiraoka had publicly noted the “horror” that began with Pearl Harbor.

Another 25 years have passed since then, and it’s clear that, in the U.S. and in Japan alike, time has done much to help nations and individuals see the events of World War II with a new perspective.

“We must never repeat the horror of war,” Abe said at the time that the Pearl Harbor visit was announced. “I want to express that determination as we look to the future, and at the same time send a message about the value of U.S.-Japanese reconciliation.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Your Vote Is Safe

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- The Surprising Health Benefits of Pain

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com