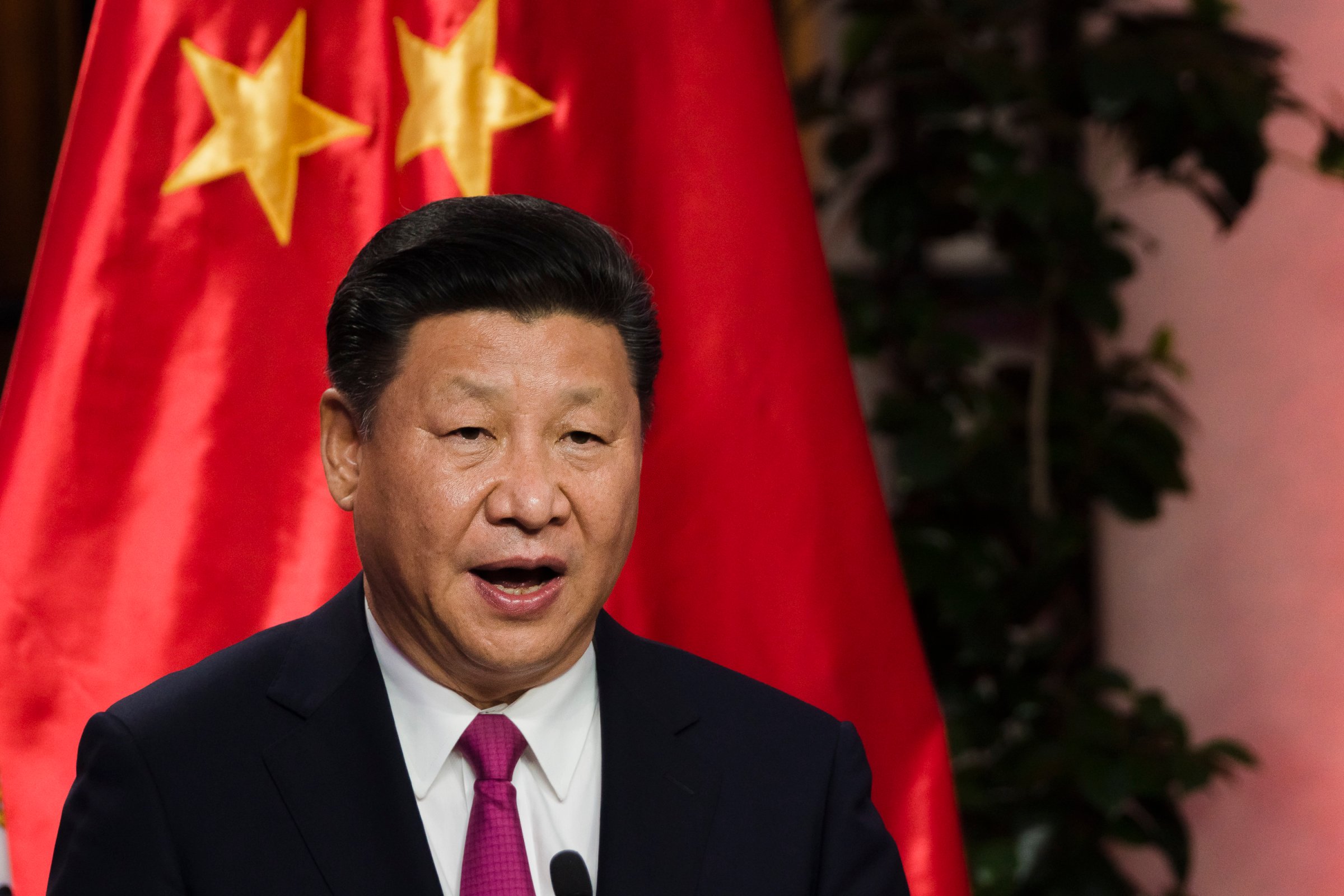

According to recent reports, China’s president, Xi Jinping, will appear at next month’s meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland—the first time that a Chinese president has attended the luxurious conclave. The annual gathering of the global elite, badly battered by the populist surge of 2016, will open on Jan. 17, 2017, just days before Donald J. Trump is inaugurated the 45th president of the United States.

In deciding to attend, Xi is making a play for influence in a world roiled by the victory of Trump. The President-elect has promised to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and other free trade agreements and recently sounded remarkably eager to use tariffs and market access controls to punish rival countries like China. Although what he will actually do in office remains unclear, leaders around the world have voiced profound concern about the future of free trade and economic openness. Xi, who also carries the title of general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has seized the opportunity this presents for China, the world’s second-largest economy, by anointing himself the unlikely champion of economic openness.

For example, at a recent summit meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) leaders in Peru, Xi declared: “China will not shut the door to the outside world but will open it even wider.” He called for the countries of the Asia-Pacific “to stay committed to taking economic globalization forward,” according to an official Xinhua News Agency report. He is likely to return to these themes at Davos.

But don’t be misled: What Xi means when he talks about openness and globalization isn’t the liberal understanding of those terms that has underpinned the U.S.-led economic order celebrated at Davos in the past. China’s economic system remains a “socialist market economy.” Xi is offering up a version of openness and globalization that is maximally beneficial to China, as part of creating an alternative economic order in which China can dominate. Let’s call it “openness with Chinese characteristics.”

Xi’s seeming embrace of openness and globalization will be immensely seductive to countries around the world that are anxious about their growth prospects and the future of the international economic system in the Trump era. In Asia, China is offering the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and will promise to accelerate negotiations. Once thought to be a China-centric companion to TPP, which excluded China, RCEP now appears to be the main game in town. But it is nonetheless enormously attractive to Asian countries because of the economic benefits it will offer and its hazy standards and requirements. RCEP will tie these countries even more strongly to China, providing Xi with a great geopolitical boon.

Beyond Asia, Xi will appeal to countries stunned by Trump’s win. He will likely promise continuing outbound investment from China around the world and reiterate that the U.S. is welcome to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a multilateral development bank proposed by China and including U.S. allies like Germany, South Korea, and the U.K. (but not the U.S., which declined to join). He will also dangle promises of greater access to China’s massive domestic market. With the prospect of a protectionist U.S. and a diminished Europe, the political and business leaders gathered at Davos may see little choice but to look to Xi for global leadership.

But it is important to remain clear-eyed about what “openness with Chinese characteristics” will actually mean. On the conservative Heritage Foundation’s list of economic openness, China ranks at number 144—squashed between Liberia and Guinea-Bissau.

China imposes intense controls on foreign investment and foreign companies that seek to do business in China or blocks them altogether. State-owned enterprises are global powerhouses but still doze sluggishly on the commanding heights of the economy; they will continue to play a role in advancing globalization without concomitant liberal openness. On other issues, such as Internet freedom, the rule of law, requirements on the information technology sector, and standards for labor and human rights, “openness with Chinese characteristics” will seek primarily to protect the CCP’s interests. For Xi, to alter a Trumpism, it is always “China first.”

But these facts are not stopping China from taking advantage of the opportunities presented by a transformed world, as Xi’s visit to Davos demonstrates. On the other hand, Trump’s Asia policy remains unclear, though the handling of his call with Tsai Ing-wen of Taiwan and his tweets regarding China are worrying early blunders. We can only hope that his administration insists that China’s limited openness to foreign investment become reciprocal to other countries’ wide openness to Chinese investment—and that, even in the absence of TPP, the U.S. continues building a strong, sustained presence in Asia’s regional economy.

One can even imagine a strange prospect at the first summit meeting between President Trump and President Xi next year. Xi would likely talk about the virtues of so-called openness while presiding over a socialist market system and the CCP. Trump would likely talk about his populist, protectionist ideas while leading an administration filled with plutocrats and wearing a made-in-China tie. They would shake hands, the leaders of the world’s two largest economies, steering the world into unknown terrain.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com