This week Michel Barnier, the European Union’s chief negotiator in the Brexit negotations laid out what Britain could expect in the coming talks over the terms of its departure from the E.U. — a strict timetable, key negotiating principles, and strong demands.

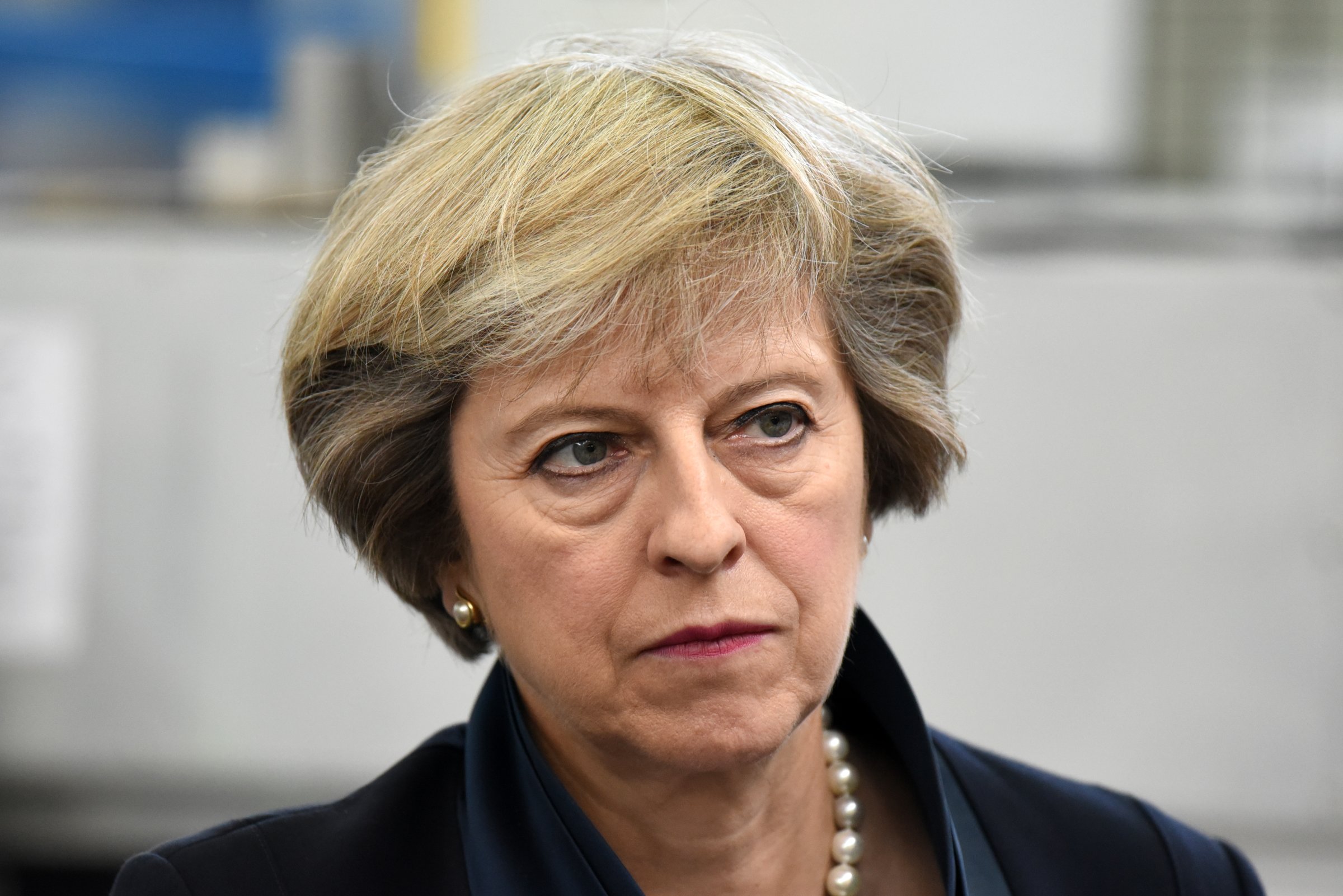

Anyone seeking a reciprocal list from London, however, had to make do with this: “What we should be looking for is a red, white and blue Brexit,” Prime Minister Theresa May said, citing the colors of the British flag. She was referring to a melange of terms – hard Brexit, soft Brexit, grey Brexit, black Brexit – to describe the different models for severing ties with the E.U., reflecting a fractured approach as her government approaches this daunting task.

It was just the latest way in which the British Prime Minister has sought to avoid giving clarity on her government’s negotiating position, having apparently worn out her reflexive catchphrase “Brexit means Brexit.” But it has not satisfied requests from clarity in Europe, or in the U.K. May on Tuesday bowed to pressure from the opposition Labour Party to agree to publishing her plans for leaving the E.U., if members of parliament (MPs) voted in favor of her timetable for starting the process of Brexit by the end of March. On Wednesday, they voted overwhelmingly to do so. But exactly when May will reveal her government’s plans, and to whom, remains a mystery.

“It’s actually quite worrisome, what we hear coming out of London,” said Jan Techau, Director of the Richard C. Holbrooke Forum, a research institute in Berlin.“It seems that there is utter cluelessness about what can be realistically achieved in this negotiation.” Since Britain voted on June 23 to leave the E.U., May and her government have given precious little information on what kind of relationship the U.K. wants to have with the bloc after it leaves. This has frustrated the 27 other countries in the union, who want to end the uncertainty as soon as possible.

So Barnier, at his first press conference on Tuesday, made clear that time was running out. The Brexit deal must be brokered by October 2018, he said, to give parliaments time to ratify any accord before the two-year deadline of March 2019. “Time will be short,” he said, in an announcement that reportedly took Downing Street by surprise. “We are entering uncharted waters. The work will be legally complex, politically sensitive, and with important consequences.”

He was using May’s own timetable of triggering Article 50 of the E.U. treaty – which formally starts a two-year exit negotiation period – before April next year. This promised date, which MPs have now effectively rubberstamped, is one of the few concrete pieces of information May has given on the issue of Brexit.

While May claims that keeping her cards close to her chest is part of her negotiating strategy, she is also struggling to unite the very different wishes of the Leave and Remain camps within her own party, and even within her own cabinet.

Highlighting these divides, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson – one of the leaders of the Leave campaign – this month publicly questioned a suggestion by Chancellor Philip Hammond and Brexit Secretary David Davis that Britain could pay to have access to the E.U. markets. The question of whether Britain might pursue a transitional Brexit deal, with certain industries retaining access to the single market after withdrawal, has also been met with indignation by Euroskeptic MPs in her party.

That issue, of access to the single market, has emerged as the main sticking point, given that the E.U. has firmly stated that such access would only be possible if Britain allows E.U. citizens the freedom to live and work there. That is a hard sell given that many Britons voted ‘Leave’ because of concerns about immigration. Consistent suggestions that they can both “have their cake and eat it” have infuriated E.U. officials.

“[Brexit] can be smooth and it can be orderly, but it requires a different attitude on the part of the British government,” said Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Dutch finance minister and head of the Eurozone area. “The things I have been hearing so far are incompatible with smooth and incompatible with orderly.”

On the point of access to the single market, the E.U. for now appears united, something of a rarity in a bloc which has in recent years made a regular spectacle of arguing among itself over issues ranging from Russian sanctions, the migrant crisis and economic policy. Maintaining that unity on Brexit as the bloc enters months and years of tough negotiations will be difficult, Techau said, as the 27 members have their own domestic agendas.

Barnier cited such unity as one of the four cornerstones of the E.U.’s strategy, along with the principle that there could be no negotiations until Article 50 was triggered, that there could be “no cherry-picking” of the single market, and that Britain should not expect an easy ride. “Third countries can never have the same rights and benefits since they are not subject to the same obligations,” he stressed.

One concession he raised was the possibility of an interim deal, to be signed at the end of the two-year negotiating period. Officials believe a full deal on new trade deals between the E.U. and the U.K. could take as much as five years to reach. An interim agreement would buy more time.

That’s necessary, Techau says, when the process of Brexit is fiercely complex and requires agreements on everything from research projects to the protection of specific regional food specialities. “[You need] an intermediate regime when the E.U. is out but some of its rules apply for a certain period of time, so that the businesses and people affected by it have more of a grace period to prepare themselves for the shock.”

But such a deal would only be possible if Britain is very clear about the nature of its future relationship, Barnier said Tuesday. May has now promised to give more clarity before the end of March, but European leaders will want more specifics than a call for a “red, white and blue” Brexit. As Guy Verhofstadt, Barnier’s counterpart in the European parliament, was quick to point out those are also the colors of the French flag — as well as the flags of five other E.U. nations.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com