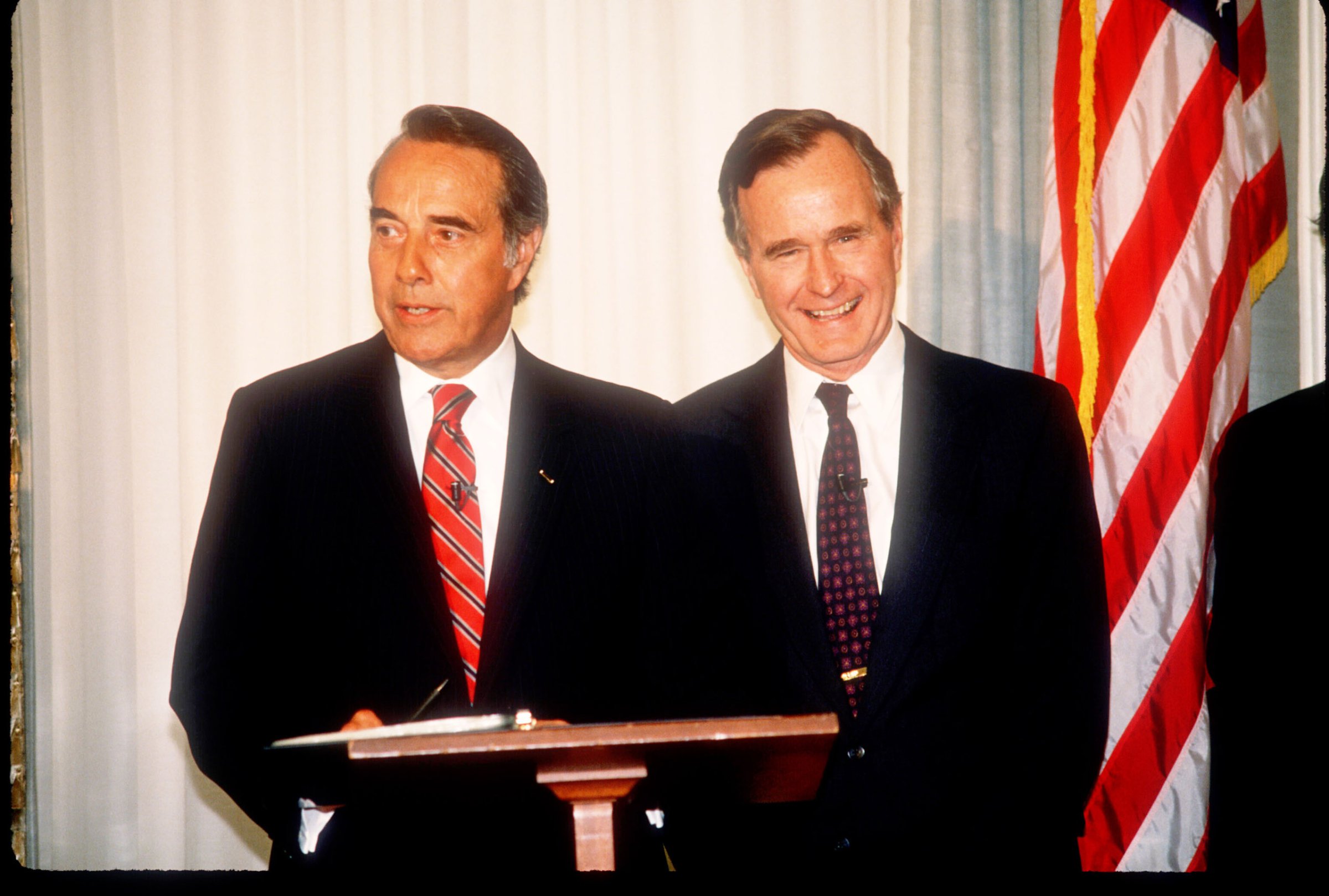

They are old men now, living emblems of American ages past. Long rivals, once allies, and now friends, George Herbert Walker Bush and Robert Dole are in the twilight of a pair of remarkable lives, veterans of wars both real and political. For them the bitterness of once-intense fights and of ancient contests is long gone. And the fights were genuinely intense.

“This is a case where two political enemies became fast, fast friends, and that’s the way it’s supposed to be,” Dole said over dinner with Bush on Tuesday night at the 41st president’s library in College Station, Texas. These were competitive politicians and public servants seeking ultimate authority in a nuclear age, and they twice, in 1980 and in 1988, faced off for the presidency of the United States. “Stop lying about my record,” Dole once growled to Bush on live television after losing the New Hampshire primary to the then-incumbent vice president. For his part, Bush often mused about Dole’s “meanness” and class resentments in his private diary.

Those fires are at last banked. Like John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in the lengthening shadows of the Founding era, Bush and Dole are among the last surviving men of the Greatest Generation who rose to rule Cold War Washington. At 92 (Bush) and 93 (Dole), they are what Jefferson referred to as “Argonauts” of old, bearing scars and nurturing memories of a world that is rapidly slipping away. “The president and I are part of a disappearing generation,” Dole said, noting that only 850,000 members of the World War II generation survived from a high of 16 million.

Today marks the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, the day that propelled America into World War II and, in the space of four years of devastating warfare unimaginable today, to true global power. “Pearl Harbor changed the world,” Dole remarked on Tuesday night. Tears beginning to come to his eyes, Dole, seated to Bush’s right, added: “I’m here for the president—I have great respect for this man.”

Bush is hosting Dole this week in College Station to commemorate the Japanese surprise attack and to present to the former Kansas senator and Senate Republican leader with the Bush presidential library’s public service award. (Dole is also in the news this week in real time: his law firm arranged the call between Taiwan and President-elect Trump that has roiled Beijing.) Bush is entering his fifth year in a wheelchair, suffering from a form of Parkinson’s Disease; Dole, too, is wheelchair-bound. Yet on Tuesday night, at a small dinner in the library, they joked and reminisced.

“He’s not getting any older,” Dole joshed, gesturing to Bush. “I am.

“Are you older than me?” Bush asked, surprised.

“Sure am,” said Dole, who has a year on Bush. “You’re just a kid.”

(They also exchanged cocktail counsel. Bush, holding a martini, asked Dole what he wanted from the bar. “A Cosmopolitan,” Dole said. “What’s that?” Bush asked, interested. “Hell if I know,” Dole said. “But they’re good, I’ll tell you that. Vodka and other stuff.”)

World War II shaped and suffused their lives as surely and as thoroughly as the conflict shaped and suffused the nation’s. Bush, a high-school senior, was walking across the campus of Phillips Academy, Andover, when he heard about the Japanese attack; Dole, a year older, was in his Kappa Sigma fraternity house at Kansas University in Lawrence as the news came over the radio. Bush’s instant reaction was that he had to serve, and he briefly considered attempting to join the Royal Canadian air force—the Brits took fliers younger than the U.S. did Convinced to wait until commencement, Bush, on Saturday, June 12, 1924, graduated, turned 18, and drove to Boston to enlist in the Navy. He’d go on to fly 58 combat missions and win the Distinguished Flying Cross for action over Chichi Jima.

Enlisting in 1942 as well, Dole’s war was darker. Enlisting after Pearl Harbor, Dole was deployed to the European theater. Serving near Florence, Italy, in April 1945, the strapping, athletic Dole was grievously wounded leading charge on a German machine gun nest, ultimately losing the use of his right arm. The senator—like Bush a man easily moved to tears—has often wept down the years as he recalled his parents’ sacrifice and the support of his hometown (Russell, Kansas) as he recovered from his injuries. He spent four years in hospitals; he suffered from a bruised spinal cord and could not walk or move his arms. Even now, he said, his sensory perception in his active left arm is off: he cannot tell the difference between a half-dollar and a dime in his pocket without pulling them out to look at them.

United as were so many of their time by their service, the two men had come from different Americas. Bush was a child of privilege in Greenwich, Connecticut, the son of a United States senator; Dole, whose family moved into their basement in order to rent out the house during the Depression, was working class; his father ran a creamery and his mother worked as a traveling saleswoman. Bush and Dole were both driven politicians, working their way to the House of Representatives in Washington. They first met at a meeting of the Ways and Means Committee, a plum assignment for the freshman Bush. “This guy walked in larger than life,” Dole recalled, “and we said, ‘Who is this guy?’ And it was George Bush.” (“Oh, come on,” Bush replied, waving away the compliment.) In 1968, Dole moved up to the Senate; Bush, who lost two bids for the Senate, set out on an appointive track in the Nixon-Ford years, at one point replacing Dole as chairman of the Republican National Committee. Dole made it to a national ticket first, running as Ford’s vice-presidential nominee in 1976. It was Bush, however, who emerged with a victory in the Iowa caucuses four years later as the main alternative to the ultimately victorious Ronald Reagan, who chose Bush as VP in Detroit in 1980.

They were not close. Dole could be resentful of—and cutting about—Bush, and Bush worried that Dole would use his leadership position in the Senate to upstage the vice president as the 1988 campaign approached. It was a reasonable anxiety: Dole won Iowa that year, threatening Bush, who recovered with a tough New Hampshire campaign that portrayed Dole as “Senator Straddle” for differing views and votes in his long legislative career.

After Bush won the presidency in November 1988, the two men came together and put aside many of their differences. Dole was a loyal soldier of the 41st president’s in the Senate. “We turned the page,” Dole recalled. “I had the pleasure of being the president’s leader for four years in the Senate.” The two combined forces to pass, among other initiatives, the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act, a longtime Dole cause that Bush embraced on the principle of “fair play” for everyone. Dole wept during a private Senate dinner tribute to Bush in the wake of Bill Clinton’s 1992 victory, a moment that touched the devastated Bush deeply.

Now, in their nineties, the two men have come to see themselves not as rivals but as comrades. “Bob Dole, more than most, has infused honor and vitality into the American political process, and contributed greatly to our progress as an open and free society,” the Bush library will announce today in its tribute to Dole. “He is the quintessential reflection of a place, and an era, when American goodness and greatness brought hope to the furthest reaches of the globe, while lifting lives and breaking down barriers to the American Dream at home.” Similar words could be said of his host, and of the Americans who answered the call to serve and to sacrifice three quarters of a century ago.

Meacham is a presidential historian, contributing editor at TIME and the author, most recently, of Destiny and Power.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com