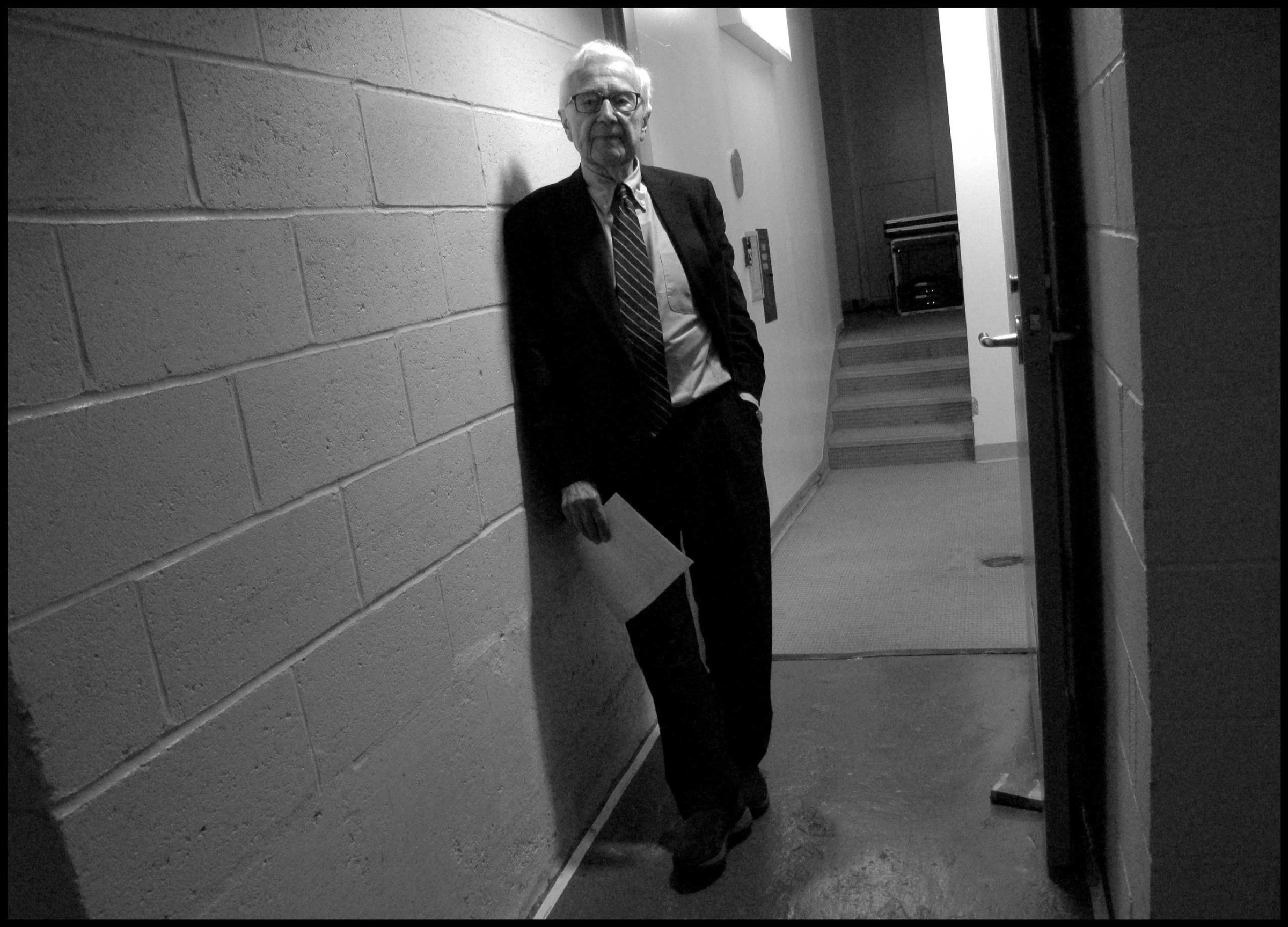

Robert Capa’s iconic 1944 shot of a soldier in the surf at Normandy would become one of the most celebrated pictures of the Second World War—but Capa did not act alone. John G. Morris, a picture editor at LIFE magazine, had assigned the war photographer to cover D-Day.

The small number of pictures with which Capa returned, which Morris published in LIFE, became legendary. But that was just the beginning for Morris. He went on to work at the New York Times, the Washington Post, National Geographic and Magnum Photos. He became a legend himself. He died on Friday at age 100, Robert Pledge of Contact Press Images confirmed to TIME.

“John’s life was shaped by war. He was a child of the Great War and lived thorough WWII and Vietnam — and every other conflict until Iraq and Syria. He followed these conflicts as an observer and a humanist,” Pledge told TIME. “When I look back at what he did with his career, war was his primary concern — it framed his understanding of humanity. Human enlightenment and understanding were always his goals.”

In late 2016, as he celebrated his milestone birthday, we asked his friends and colleagues to reflect on his century. Here are those memories.

Russell Burrows, son of photojournalist Larry Burrows, with Barbara “Bobbie” Baker Burrows, a LIFE photo editor

For three quarters of his life, John has had to share the anniversary of his birth with that day of infamy. It’s a concurrence mentioned in several tributes to John and, certainly, the 7th of December should never be forgotten. But that’s a rather grim connection.

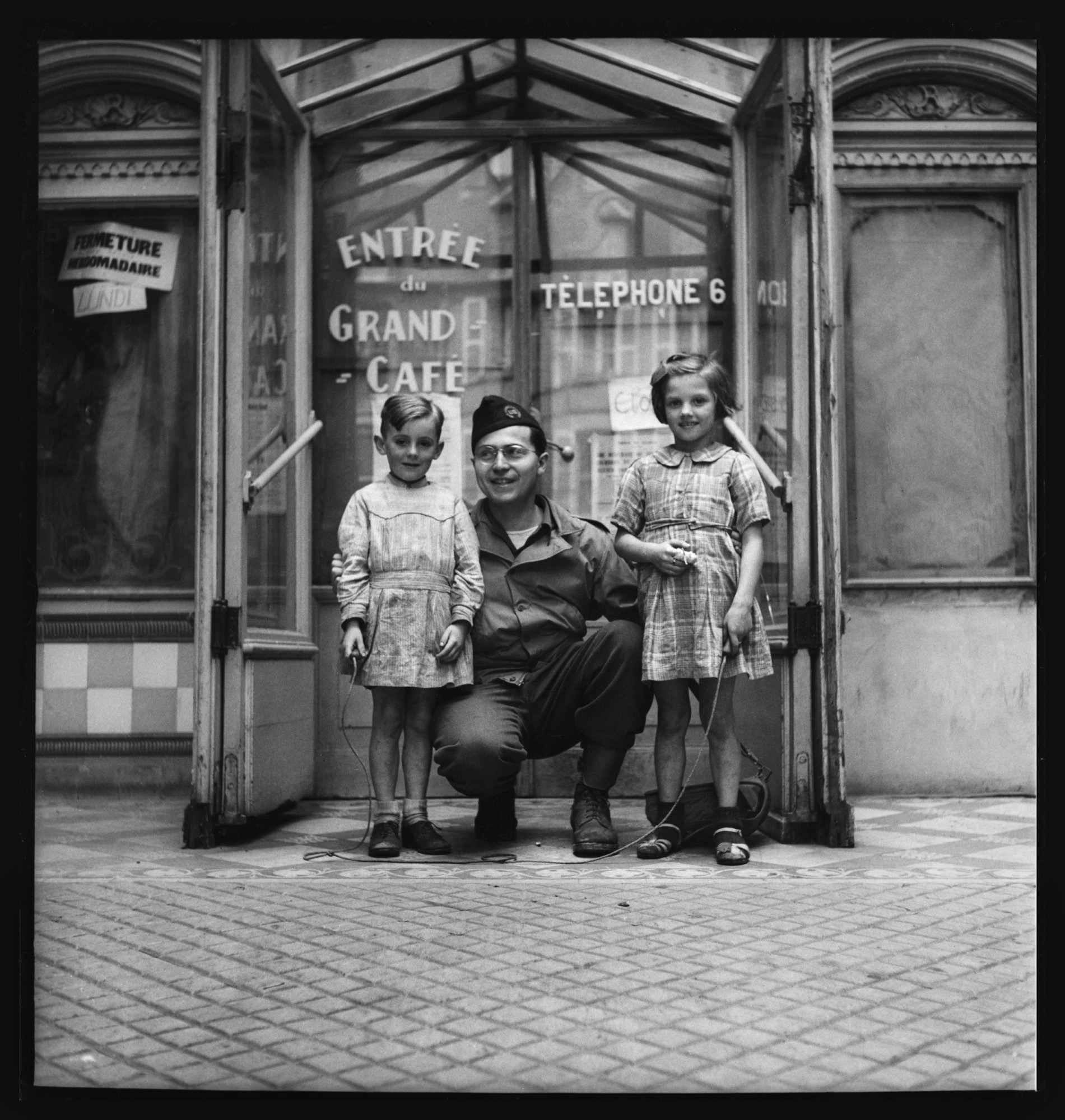

It’s another day — famous too, and grim, but one that has ultimately come to be viewed much more positively — D-Day, that became central to John’s life. With the assignment of a team of great photographers to cover the invasion, and his own journey from wartime London to Normandy to Paris, John began a remarkable career. The stories that followed are oft-told and familiar to anyone with a knowledge of 20th century photography.

Ten years younger than John, my father had been an office boy who eagerly became a photo lab technician in the LIFE London darkroom that was part of John’s domain. It was the beginning of what, through three generations, is now a long family friendship. (Who could have imagined that 60 years after those lab days, John would be accepting the Prix Nadar, for the photography book of the year, on my father’s behalf?)

When Bobbi Baker joined LIFE in the 1960s, John was long gone from the magazine and well established as the picture editor of the New York Times. Just as illustrious, Richard O. Pollard was solidly in charge as LIFE’s director of photography. When Dick suggested that the Times had some photographs that LIFE needed and that “Johnny Morris over there” knew all about it, he told Bobbi to give him a call. The young photo researcher dutifully did so.

“Johnny, we need those pictures.”

It wasn’t long before John made the delivery himself! Bobbi learned who John G. Morris was, and another connection was made between our families (she didn’t actually become a Burrows for a few more years).

We’ve known John, his wives, his family, we know John’s politics (and he will passionately share them with anyone), but in the U.S., in Britain and in France, we’ve seen his influence on photography — and few can match it. Happy century John.

David Friend, creative development editor at Vanity Fair and a former LIFE director of photography

John Morris has been the Zelig, the Svengali, the Rasputin, the Diaghilev, the Bob Fosse, the Vince Lombardi of 20th century photojournalism and humanistic photography.

He honed his intellect at his beloved University of Chicago. He developed his journalistic instincts at LIFE. He became an entrepreneur and herder of stray cats (and panthers) at Magnum. He stiffened his backbone at the New York Times. He has been the keeper of the flame of Robert and Cornell Capa, of W. Eugene Smith, of so many other giants of the medium.

No living picture editor has been involved behind the scenes in the creation of more famous photographs over a longer span of time. And, from his post in Paris, he remains a dedicated defender of American liberalism in a rising sea of intolerance.

Hats off to John; to his friends and wives no longer with us; to the FIRST hundred years.

Jean-Francois Leroy, director of the Visa pour l’Image photojournalism festival

John G. Morris is this kind of guy you’re always impressed to meet. He had a friend called Robert Capa. Another called Henri Cartier-Bresson. So, like everybody else, I was really intimidated during our first meeting. But he is so generous, he tells you all of the stories you’ve always wanted to hear. He’s a living memory and such a good friend!

I have had the privilege to have another friend, one year older than John: David Douglas Duncan. Both of them are proof that this photo field is a very good way to have a long life!

One day, at a print auction for the French photographer Françoise Demulder when she was sick, John put in one of his pictures. I bought it. A few years later, when he had his show in Perpignan, he signed it: “To my first customer.”

Robert Sullivan, editor of LIFE Books from 1990 to 2015

In my years at LIFE in the 1990s and into this decade, I got to meet and, in certain cases, to know some legends: Eisie, Carl, David, Martha, Gordon, Harry, Henry, Bill and on. John—Loengard, who I still know, but also Morris—was a legend, but I never met him (the Morris, John); But who could not be intrigued and inspired by John’s career, success, and dedication? I learned from my colleague Bobbi, whom you’ve heard from here, that he is the best kind of person. I heard that from others, too. I don’t doubt it.

As John turns 100, I couldn’t be happier—I’ve been rooting for John and David [Douglas Duncan] for a couple of years now—and I think the one thing I can say about John is, with LIFE, I always wanted to do away with the myths. People—those damned media people—always called wanting to know who kissed the nurse and how Capa’s D-Day film distilled to so few images, among other things. I referred folks to Loudon’s terrific book, or if pressed, said, “no.” Eisie didn’t take notes, of course he didn’t. A former nurse just died this year, in 2016, and got national obits as THE ONE in the photo. She may well have been. Or you could have been. And it doesn’t matter. The sailor and the nurse were intended as universals, and they are best seen that way. Elise never said who was who, and surely Eisie never knew.

John Morris was a young man working for us, which is to say LIFE and TIME Inc., in London when Capa’s cobbled shipment arrived from the front lines in Normandy. I firmly believe that John developed capably what images could be capably developed. Everyone was in a hurry. There’s no scandal here. We in the U.S. are in a season of scandal-mongering about every little thing, and I reflect that historically there are lots of “scandals” that have attached themselves to our—to LIFE’s—story (again: go to Loudon’s book for clarity).

Yes the images look shaky, and that’s part of their power. Was that a product of bombs on the beach or emulsions in London? If the latter, history—not to mention Mr. Spielberg—owes John Morris a greater debt. He took us there, not as much as Capa did, but he played his part.

Happy birthday, John. I do hope we meet down the road.

John Loengard, a photographer and picture editor at LIFE

John G. Morris is truly a gentleman. Our relationship over the years has been pleasant but only on brief and tangential meetings. I met him first when he was managing Magnum in the mid-1950s. His unwavering belief in the value of journalism by camera impressed me then, and that conviction is as fresh in him today as it was 60 years ago. Bravo! And happy 100th birthday!

Liz Ronk is the History Photo Editor for TIME and LIFE.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitterand Instagram @olivierclaurent.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com