Few European politicians celebrated the election victory of Donald Trump quite as enthusiastically as the British populist Nigel Farage. After the success of his decade-long campaign for the U.K. to leave the European Union in June, Farage began stumping for Trump on the campaign trail, urging American voters to support the anti-establishment revolt that had helped turn the British electorate against the E.U.

The shock result of the U.K.’s Brexit referendum was an inspiration to Trump and his campaign team, who then invited Farage and his fellow Brexiteers to visit Trump Tower a few days after the presidential elections. On Nov. 12, Farage thus became the first foreign politician to meet with the new U.S President-elect. They even posed for a photo together that day, grinning in front of the gilded doors of Trump’s penthouse apartment in midtown Manhattan.

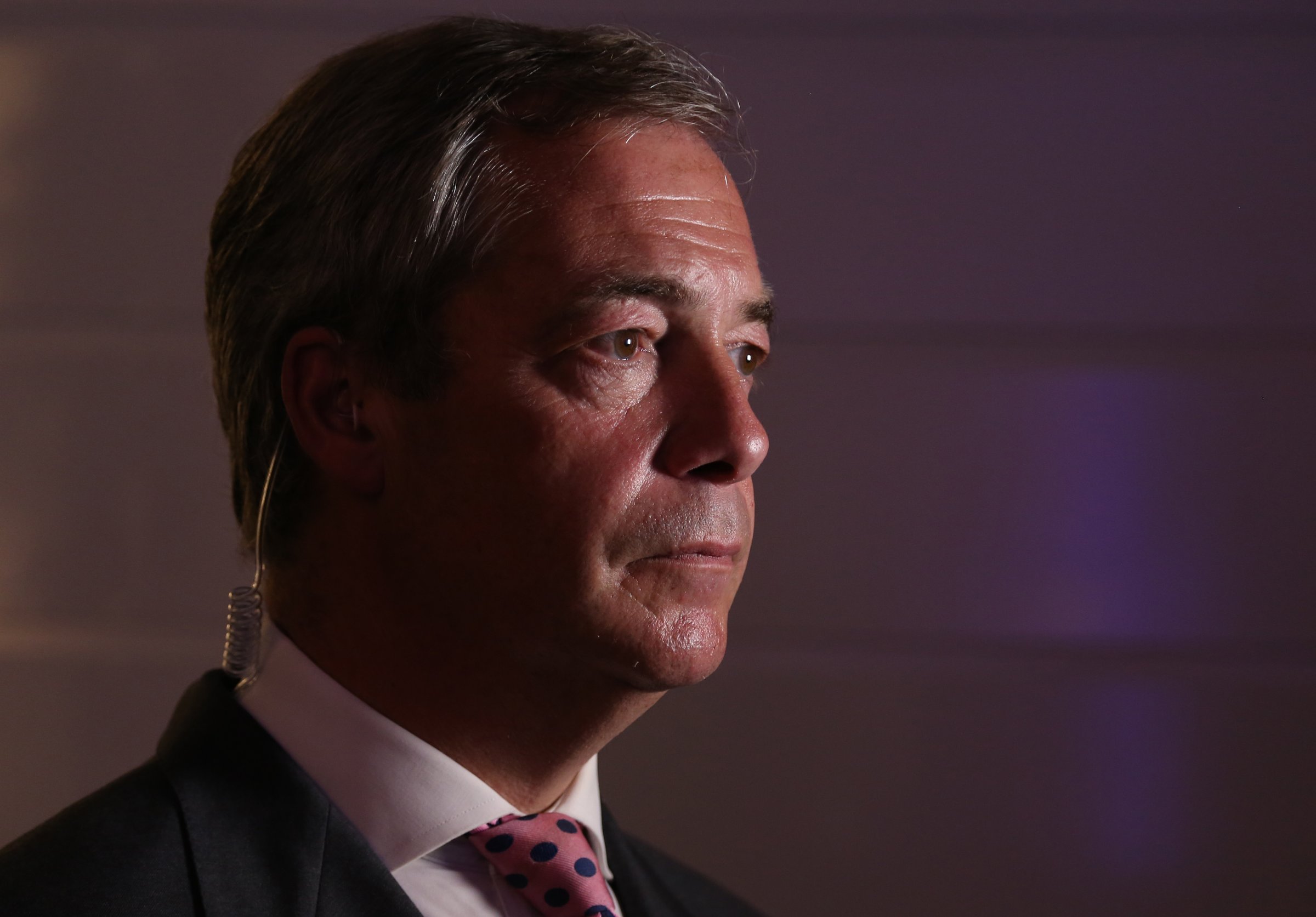

A couple of weeks later, Farage sat down with TIME at one of his favorite restaurants in London to talk about the movement that has brought him and Trump into alignment with an ascendant class of Western populists, and what their movement has in store for the U.S. and Europe:

How did your relationship with Donald Trump develop? What was the connection?

I’d been writing for the past 18 months for [far-right news site] Breitbart on quite a regular basis, and [its director Stephen] Bannon backed Trump right from the early days. So my connections into Trump were through this team of people, whom I’ve known for some years.

How did you end up speaking at Trump’s campaign rally in Jackson, Mississippi, in August?

[Trump’s campaign managers] Bannon and Kellyanne [Conway] both saw Brexit as an inspiration. They wanted a big Brexit injection into the campaign. They wanted the message that I gave, that if you get off your backside you can beat the establishment. So that was how it all happened that I ended up in Mississippi.

How did you become the first foreign politician to meet with Trump after the elections?

We kept very closely in touch [during the campaign]. I went back to St. Louis for the debate. I went back to Las Vegas for the debate. I was in the spin rooms at a time when not many people were. I defended [Trump’s] actions by saying, ‘It wasn’t pretty, but he wasn’t running to be Pope,’ which I thought was pretty good, really. But it was tough.

And after the elections?

We turned up in New York, and Bannon agreed: ‘Come to the office.’ And they’re still working full pelt, because the elections have just finished… And we’re actually shut inside the place, because there’s actually 25,000 protestors on Fifth Avenue. So we can’t go anywhere, for hours! And I did say, I’d love to speak to Donald, I’d like to congratulate him either by phone or a quick hello, and they said, ‘Alright, come up.’ So up we went, and he had a lot of time for us, which was remarkable.

What did you talk about?

Look, we talked about a lot of things. We talked about the campaign. We talked about our shared experiences of being demonized. No surprise there. We’re two of the most vilified people in the Western world. We talked about Anglo-American relations. He’s a big Anglophile, plus he’s got investments in Scotland. So it’s a big part of who he is. And we talked about a whole load of other stuff, which I’m not going to go into. We talked a bit about what I’m going to do next. And it was great. He agreed to do that picture, which was amazing. It’s the first time he’s ever been photographed without a tie! No, seriously! It shows that he was very laid back. He was relaxed. And he himself saw Brexit as, ‘Thank God for Brexit! Brexit changed the mood. Brexit gave us the impetus.’ Normally, when New York catches a cold, London sneezes. We follow social, political, commercial trends. This was one of the few times when this little country set the trend somewhere else.

About a week and a half later, Trump tweeted that you would do “a great job” as the British ambassador to the U.S. How did that come about?

As far as I’m concerned, a bolt from the blue! I had no idea it was going to happen. I was in Strasbourg. It was three in the morning, and I left the bloody phone on. So the phone rang, and then it just kept ringing. That was it. I was amazed by it. But, it was utterly typical of him, if you speak to people who know him, that if he believes in you, he trusts you, then you’re the man he wants to deal with.

Could you play a diplomatic role in the future?

Look, it’s up to the British government, an incredibly snobby, ghastly bunch of people, all career politicians. They don’t really care about the country. They just care about the Conservative Party. And they’ve all seen me as a threat to it. So by rebuffing me completely, at best they’re being tribal politicians, and at worst, they’re putting their own interests ahead of the interests of the country.

But you would be happy to represent the U.K?

I would be happy, formally or informally, to do anything I can to cement the relations between our two great nations. …If we were in the world of business, and you’re in Downing Street, and you look at Trump in America as a client, the first thing you would do is find the person with the connections. And I’ve got those connections! I’m in a position to help, but they don’t want me. It’s bizarre! I’ve felt my whole life in politics like that. I’ve always been the outsider. I’ve always been regarded as some extraordinarily dangerous figure. I’m none of those things! I’m just a middle-class boy from Kent who likes cricket, and who happened to have a strong view about a supernational government from Brussels.

You are no longer leader of UKIP. What’s next for you?

I’m thinking of university speeches, various things like that, to try to put the argument that the destruction of the European Union is not the destruction of European civilization. And it could be a completely new beginning for a different type of Europe. …What the British referendum did was to end forever the argument about inevitability, that people all across Europe would say, ‘We don’t like it, we don’t want it, we’re uncomfortable with the direction it’s going, but it’s probably inevitable.’ That argument is gone!

What would be the next domino you expect to fall in the E.U.?

If I knew that, I’d be at Ladbrokes! I wouldn’t be talking to you. But I do think Italy is the wild card. If you ask me right now what’s going to happen in France, I think Marine [Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Front] will get 42% [in the presidential election due next spring]. I think she’ll get a huge big second. But I don’t think at the minute she can win. But hey, it’s not impossible.

Will you endorse her?

I don’t know. I’ve never said anything negative or nasty about Marine. But I’ve never said anything nice about the National Front. That’s pretty much my position.

What is the force that you, Trump and all these populist politicians on the right are tapping into?

There’s a lot of crossover. It’s not as working class as people think. It’s not people with nothing that are supporting these movements. It’s generally people who aspire for their kids to have as good a life, or a better life than they had, but now see that as being impossible… Economic issues have been a very big driver. I’d love to tell you that everyone who voted Brexit felt like me about the country, about the Union Jack and the cricket team. But I don’t think that there’s as much romanticism in it, perhaps, as people think. I think it’s people saying, ‘You know what? Life isn’t getting any better. And no one’s listening. And no one is offering us any choices at all.’

Is this movement sustainable, or is it just a protest vote, a swing of the political pendulum?

Well, they’re in charge in America. They’re in charge! That’s why, if Brexit was big, Trump is huge! I get your point that rebellions can go up to a high water mark and then go back. I get that. But the fact that Trump is in charge in America, if he gets this half right, the Republicans will be in power for years.

With Trump in the White House, what would be your vision for Europe and the West?

For America it’s clear. They will make their own decisions, and chart their own course and be under much less influence from anybody else. In terms of Europe, the time has come for us to offer an alternative, a concept of nation states that can be incredibly close together, but they do so on the basis of cooperation, not political assimilation.

What do you say to the argument that the integration of Europe was meant to avoid wars like the ones Europe saw in the 20th century?

I can’t think of a single example of two mature democracies going to war with each other in the 20th century. It’s where there was an absence of democracy and a breakdown of democracy that we finish up with these wars. … You would not be getting real extremes of left and right [in Europe] unless people felt that their ability to change their future had been taken from them, and if people weren’t rejecting a false identity being put upon them. I mean, who wants that flag? Who wants a European identity? Virtually no one! … I’m in no doubt that the European project is finished. It’s just a question of when. And I don’t fear a return to insularity or negativity or hatred. In fact, quite the opposite. I think we’ll just return to being good neighbors.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has pointed out that Western cooperation is rooted in shared values, like tolerance, inclusiveness, respect for minorities. Is she wrong? Don’t these values tie the West together?

Does she mean Christian values? No, she wouldn’t talk about that! What about our Christian heritage? What’s happened to that, Mrs. Merkel? She doesn’t mention that. I think we need to be more assertive about who we are, what our culture is, what our background is, and that isn’t giving insult to anybody. It’s almost as if Mrs. Merkel is trying to redefine who we all are as countries. And I think that’s a mistake. Also, she’s desperately covering up for the biggest political error that any Western world leader has made in 70 years, namely: Let everyone come! That, more than the euro, is now leading to massive resentment all over Europe. Why should Germany decide what our immigration policy is? That’s really what’s happened.

But Merkel’s decision to allow in refugees from Syria and other parts of the Muslim world was a reflection of European values and, in some ways, of Christian values, was it not?

What, like driving women down? That sort of thing? Lovely!

Are you saying the Christian tradition is inherently opposed to the Islamic tradition?

It doesn’t have to be opposed to it. But if you’re not willing to stand up for who you are and what your values are, then they will get crushed or pushed aside. There’s no attempt to do that from Merkel or anybody else. And I think that’s very worrying. I think the public find that very worrying.

Would you support Trump’s campaign promise to ban Muslims from entering the U.S.?

Well, he did amend that, I’m pleased to say. He did amend that to ‘extreme vetting.’ I wish we’d been extreme vetting. I wonder how many terrorists Mrs. Merkel has invited into Europe. Well, we’ll find out in the next five years, won’t we? … I think extreme vetting is very sensible. And what Mrs. Merkel did was the opposite to that.

What made people come around to your ideas about Europe? Why now?

It was when they saw in East Anglia that getting a [doctor’s] appointment was virtually impossible, that getting a kid into the local primary school was extremely difficult, that their wages hadn’t risen for ten years… And the social dimension, which affects some, like a quarter of [the English city of] Peterborough is now a Polish quarter with zero integration and lots of separation. And I think it was that – it was the impact on people’s lives – and then making the connection between that and E.U. membership. That, I think, was the key to the whole thing.

Why was the shared sense of European identity not strong enough to counter those nativist feelings?

There’s no demos! There’s no sense of being. The European project doesn’t work. They tried like crazy for decades, and it didn’t work. Globally the world is breaking down into smaller units. It’s a more interdependent world. But in terms of governance, and the comfort people feel, the world is breaking down. We’ve gone against all of this. And we’ve used the shadow of two wars to do it. It’s completely understandable. Because, after all, if countries trade with each other, they’re less likely to go to war. But if they’re democratic countries, they’ll never go to war.

This article has been edited for length and clarity

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com