When it happened, Chick Takara was 12 years old—old enough to work on Sundays, alongside his brother, washing dishes in a restaurant in Honolulu to help pay their family’s bills. Dec. 7, 1941, was a slow morning. A taxi driver, in for a cup of coffee, got the young dishwashers’ attention. Go look at the harbor, he said. The Navy is using live ammo for their drills today. The boys climbed a ladder to the roof and looked toward Pearl Harbor.

“Sure enough,” Takara now recalls, “we see hundreds and hundreds of gray and white powder puffs all over the sky.”

The boss told the boys to go home—about a half an hour by trolley, even in streets eerily empty of cars, and then a sprint to the tenements where the Takaras lived. Chick Takara is 87 now, but he remembers that his mother was standing outside talking to a neighbor, their arms full of laundry. In his memory of the day, he’s yelling as he runs: This is war, Mommy!

He was right.

The neighbor turned to go upstairs for the rest of her wash. A streak swooshed across the sky—gray, not red like in the movies. Loud. The bomb hit the house, with the neighbor inside.

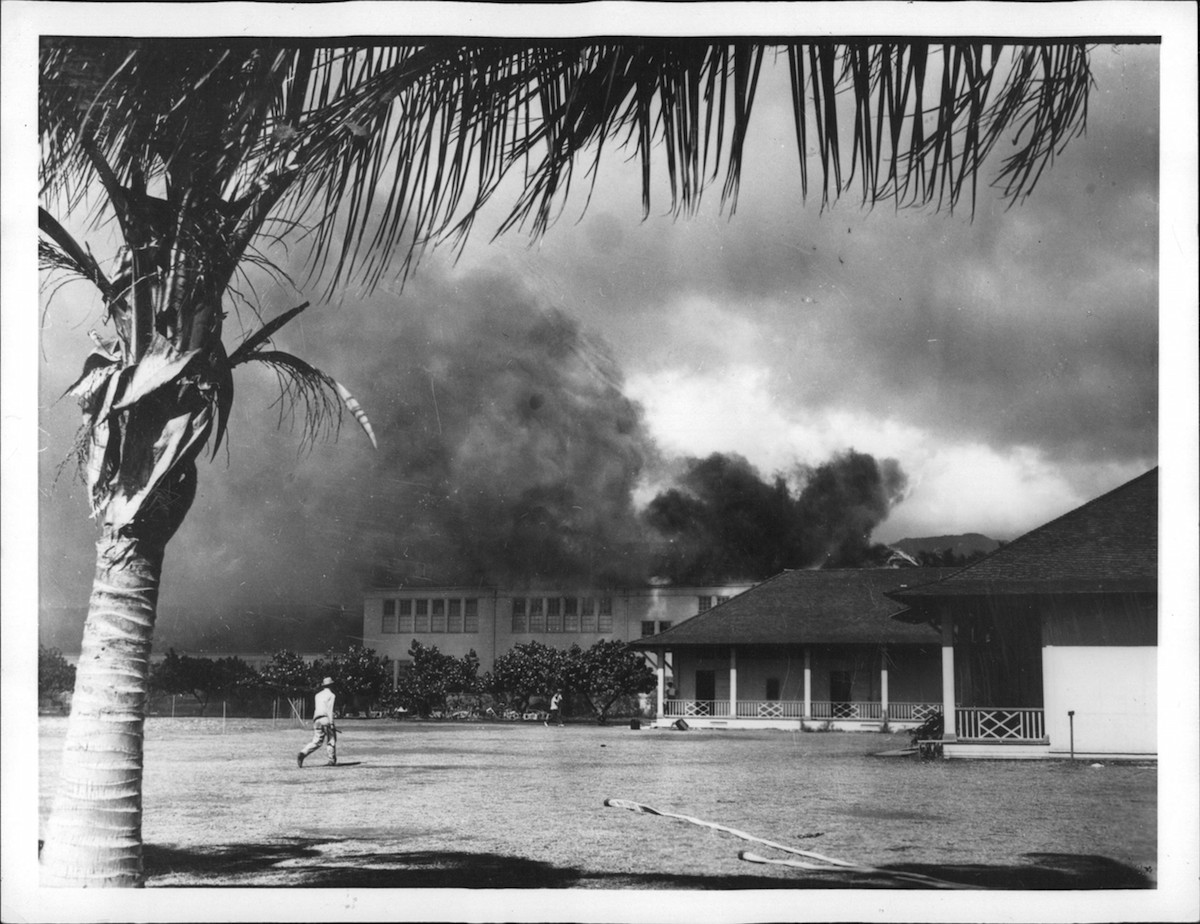

Takara, watching, was too terrified to scream. Among the wooden tenements, the fire spread quickly.

Chick’s father told the six Takara children to hold hands. The plan was that they would walk to a nearby stadium and sit down on the 50-yard line, where at least they would die together. But the principal of the local Japanese school—part of the large Japanese-American community that made up about 38% of the people living in Hawaii in 1940—intercepted them, offering shelter. The family stayed for weeks at the school, sleeping on the tatami mats in the room where young girls once sat to learn to sew kimonos. The school’s auditorium also became the clearinghouse for Japanese residents, now declared enemy aliens, to turn in the belongings that were no longer allowed to belong to them: radios, binoculars, weapons. When the family was allowed to try to salvage what they could from their home, Takara found coins melded together by the fire—a memento he keeps to this day.

Now, 75 years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the day that threw the United States into World War II has lived up to the prediction made by President Franklin Roosevelt that week. The date lives in infamy. Yet despite being one of the best-known days in modern American history, some of its stories are only just making their way into the world. Chick Takara, for example, says that for many years he felt that he must be the only one to have spent a lifetime with this particular side of the Pearl Harbor story, the perspective of a Japanese-American child in Hawaii. The story, however, is a valuable one—especially as people who were young in 1941 become the only ones left who remember.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Edwin Nakasone was 14. He remembers eating Cornflakes when, through the screen door of his home, he saw the planes coming through Kolekole Pass, to strafe Schofield Barracks. Like Takara, his first thought was that the Navy must have made a terrible mistake in their drills—drills were normal, planes overhead commonplace—until he looked up and saw the red circle marks under the wings of the planes overhead. The planes were Japanese.

“I dashed back in the house, turned on the radio. And sure enough, Webley Edwards—I still remember the announcer’s name, there were only two stations in Hawaii at that time; Station KGMB, Webley Edwards—was saying, All service personnel, return to your base,” Nakasone says.

Nakasone, like the other young Japanese-Americans of Hawaii at the time, encountered a strange world. Black-outs at night. Hiding under the bed at the sound of planes, hoping that the mattress would stop bullets. Martial law. But Hawaii was a true melting pot and, by virtue of distance and demographics, the large Japanese-American population did not face the same broad incarceration that was seen on the mainland during the war. But that didn’t mean things were easy. Civilians of Japanese extraction who worked for the Army lost their jobs, and internment did happen, though it affected a much smaller portion of the population. Documents from the time show that President Roosevelt advocated removing Japanese people from Oahu, the island that is home to Pearl Harbor. Evidence suggests that the reason such a plan was not pursued was not moral outrage, but rather that the military officers who would have overseen such a move could tell that it would be impractical and a drain on labor resources. Nakasone’s parents made sure they had no pictures of the Japanese emperor in the home, or anything else that would raise suspicion.

In the years that would follow, Nakasone—perhaps because he became a history teacher, in Minnesota—found himself often discussing what had happened back then. “What I saw is still imprinted on my mind,” he says. That willingness to discuss the day, however, is not shared by everyone who was there.

Keiko Nakata was 17, working that morning with her mother and her sister Akiko in their family’s taro patch in Kahaluu. She figured out that it wasn’t just a drill when a bomb fell in a yard nearby. From her home she could hear the sound of gunfire.

In the days that followed, her parents burned the books they had brought from Japan. They built a bomb shelter and, when the children returned to school, they went with gas masks in tow.

Though certain memories of that time remain vivid to Nakata, some of the details of have since blurred. How long was she out of school? How long did she carry a gas mask every day? How many weeks did she sleep in the bomb shelter? For many years after, Nakata did not discuss what had happened. Her parents didn’t talk about it with the family when she was young. She in turn did not discuss it with her own children.

“We don’t know their history,” says Sandra Hino, 55, her daughter, who also lives on Oahu. “This generation, they generally don’t bring it up, because of bad feelings. They just have us focus on the future.”

Hino says she didn’t fully understand what her mother had been through until she herself was an adult. But she insists on talking with her own son about his grandmother’s experience, trying to set a new precedent. “Many in her age group are not here anymore,” Hino says. “So if she goes without sharing, then none of us will know the actual history.”

Revisit 1941 in virtual reality with LIFE VR’s Remembering Pearl Harbor

Walter Oka was 13. He was listening to the radio with five of his siblings when he heard the explosions; from their home in Aiea, they had a clear view of the harbor. When the USS Arizona exploded, the blast was strong enough to make him stagger. In his memory, the wooden coffins that were brought past his home that day, on their way to a temporary burial ground, were stained with blood.

In those first days after the attack, U.S. officials were the ones who seized his brother’s ham radio equipment and, a few days later, FBI agents came back to the house. They had heard that one Walter Oka had been studying the coming and going of the ships in the harbor. When they found out their suspicious figure was only a 13-year-old boy curious about ships, they left. Even when the prejudice he faced then continued into later life, he says he was never really reluctant to discuss what happened. Instead, the reason he didn’t discuss it was that there were few opportunities to do so.

“Nobody asked,” says Oka, “and I never volunteered.”

Recently, however, that has changed. Now that there are not many around who remember that day, he finds that people stop and think when they find out he’s from Hawaii. Now, they want to know whether he was there during the attack. He’s happy to tell them. By this point, he even has a PowerPoint presentation prepared on the subject. People want to know what he saw, what he thinks, what there is to be said about what happened.

That fact is all too clear to Stacey Hayashi, a 41-year-old yonsei—fourth-generation Japanese-American—who grew up in Hawaii, one of many of her generation who did not know about what her elders had seen. “When I was a young kid my dad would say stuff like, oh, Uncle Ko—my grandpa’s younger brother—was in the [Japanese-American World War II Battalion],” she says. “I’m thinking, wow, that’s ancient history. I’m a girl. I’m 9. I don’t care.”

When she was in high school, she began to appreciate the remarkable ways the people in her grandparents’ generation responded to the coming of war, particularly the lengths they went to be able to serve in the military despite the barriers they faced due to their race. Hayashi, a former software engineer and dress designer by trade, has written a comic book about that story and is now working on a feature film project about it. That work has brought her into touch with many of the Japanese-American Hawaiians who lived through that time—including those who were too young to fight, people like Chick Takara—and has taught her how to coax out their stories.

“[In Japanese culture] you’re taught not to talk about yourself and to not share your stories,” Hayashi says. “That’s seen as bragging. A lot of them don’t want to talk about their stories because they’re too painful, but with Japanese-American veterans there’s this added layer.”

But, as Hayashi sees it, breaking through that layer is crucial.

One reason goes back to the different experiences of people of Japanese descent on the West Coast of the mainland, who faced internment and exclusion during the war, and those in the larger and more integrated population in Hawaii. For example, the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team—comprised of Japanese-Americans, many from Hawaii—became the most decorated combat unit, for its size and service, in all of American military history to that point. As Hayashi sees it, these two experiences illustrate the importance of embracing immigrant communities. “[In Hawaii] you have this overwhelming response to help your country. Almost 10,000 guys signed up and the ones who didn’t make it, they cried, because they wanted so badly to serve,” Hayashi says. “And yet on the West Coast you treat them like they’re suspected. Why would you want to fight for a country that treated you that way?”

But, she says, having worked to gather these stories for over a decade, she’s noticed the same shift that Oka has seen his daily life, the shift that Hino has seen in her own family.

With age, though some may find it more difficult to talk about the past, others of the veterans and survivors with whom she has become close have become more willing to share their stories. “I think that while they were younger they felt like, well, let’s just do what we can to make the world better,” she says. “That was their mindset, and it didn’t occur to them that sharing their stories would be helpful in making the world better.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com