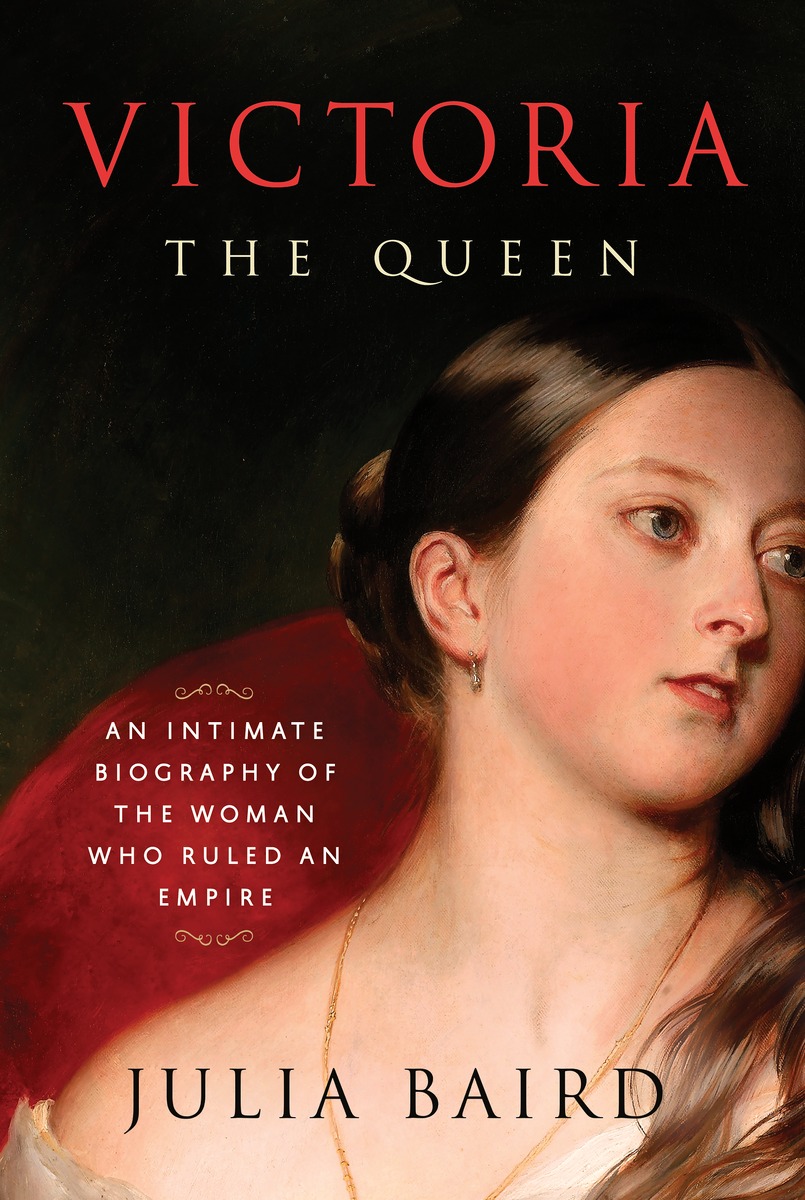

Julia Baird is the author of Victoria: The Queen, An Intimate Biography of a Woman Who Ruled an Empire

In the thick of the Boer War, when the British Foreign Secretary told Queen Victoria about a terrible setback, her response was brusque. “Please understand that there is no one depressed in this house,” she said, “we are not interested in the possibilities of defeat; they do not exist’.[i] The formidable woman, then almost blinded by cataracts, and struggling to walk, had ruled for 60 years and was not inclined to tolerate any signs of a lack of resolve or patriotism. She flatly refused to accept defeat—and as a woman who inherited rather than won power, she never had to face the prospect of an election, a privilege female politicians around the world might simultaneously bristle at and envy.

Just like Margaret Thatcher, Queen Victoria was “not for turning.”

Sometimes, though, you have to.

After decades of steaming through obstacles, opposition and vilification, in the moment of her most recent and spectacular defeat, Hillary Clinton was finally forced to turn: she was sad and apologetic but held her head up. In her first public appearance since the defeat, she admitted she struggled to get out of bed. No kidding. Every time I see Clinton now, I rub my eyes. I would have been happily embedded in Netflix, snacking like a fiend, moodily trying to avoid composing angry haikus on Twitter.

And so it was for the woman who was almost the first female POTUS, who said at a gala a few days after her defeat: “I will admit, coming here tonight wasn’t the easiest thing for me. There have been a few times this past week when all I wanted to do was just to curl up with a good book or our dogs and never leave the house again.” She didn’t mention the pint of ice cream, but we all suspected it was there.

So what lessons would a doughty queen like Victoria have for Clinton in the days ahead? What could a woman who inherited power say to a woman who almost won it? Apart from: “there’s no one depressed in this house”?

Perhaps it is as simple as this: surely the greatest test of stamina is not just if you can get to the finish line, but whether you are able to stay upright after crossing it. Clinton’s stamina, like that of Victoria, who lived to 81 and worked until her eyes wore out, is demonstrably phenomenal, despite suggestions by the President-elect to the contrary.

In short, Victoria endured. It may seem banal or obvious, but despite all the pressure to hand her royal power over to first her mother (and her mother’s advisor), then her husband, then her son, she refused to budge. She endured grief, attack, illness, praise, love, loss, loneliness and fear—and kept going.

Victoria was acutely conscious of the times when she was in favor with her people—she was almost deafened by a wall of sound that greeted her every time she left her palace—and she noted cheerfully was that the best part of being shot at (she survived eight assassination attempts) was that she was instantly swamped with sympathy and adoration.

But part of the queen’s capacity to endure was that she cared more about what she thought of other people than what they thought of her. It was not as important to her to be likable; she could be redoubtable. (She also abandoned any pretensions to beauty but deeply admired it in others.)

We tend to assume that there is one ceiling to smash, one way for women to progress, one job to aspire to—the highest, the hardest, the one made of glass. But Clinton, by her sheer longevity, has also smashed a bunch of stereotypes and expectations about how older women behave—how visible, important, weighty they are. This is of itself huge.

As British author Catlin Moran wrote, the very act of Clinton running for president redefined her thinking about the lives older women can live. Instead of assuming that women should grow herbs or shrink from public view after their physically fertile years have passed, she wrote, with Clinton’s announcement that she would run for president, suddenly we were presented with the specter of a woman leading the free world at age 67:

In a stroke, this gives women a whole extra act in our lives. Another 30 years, minimum, in which we can continue to grow in power, wisdom, accomplishment, ambition and balls. The female narrative arc is reinvented like that – from slow decline to soaring upward thread. Clinton has made the sexual power of being a young woman – so often our gender’s greatest currency – look as nothing compared with what you can get in your seventh decade: the world.

Clinton didn’t get the world. But she got very, very close. And she got up again. Despite the universal allure of the couch-and-remote combination.

And in doing so, she expanded the boundaries of the female imagination in a way that is difficult to measure. Victoria did too; she opposed female suffrage but inspired a generation of suffragettes—and permanently stamped a powerful female face on the British psyche, arguably paving the way for the likes of Thatcher and Theresa May.

Stamina isn’t just eating a thousand Philly Steaks while beaming for the cameras day after day for an 18-month campaign—though kudos for that—but also staying upright when you have been clobbered by fate, fear or loss.

The possibilities of defeat exist alright. But the possibilities of enduring do too.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com