There’s a lot we can’t know for sure before election night: who will vote, who will win, who will refuse to concede. But no matter what happens, we do know that the media–specifically, the Associated Press and the major TV news networks–will play an outsize role in calling the results days before all the votes have been counted.

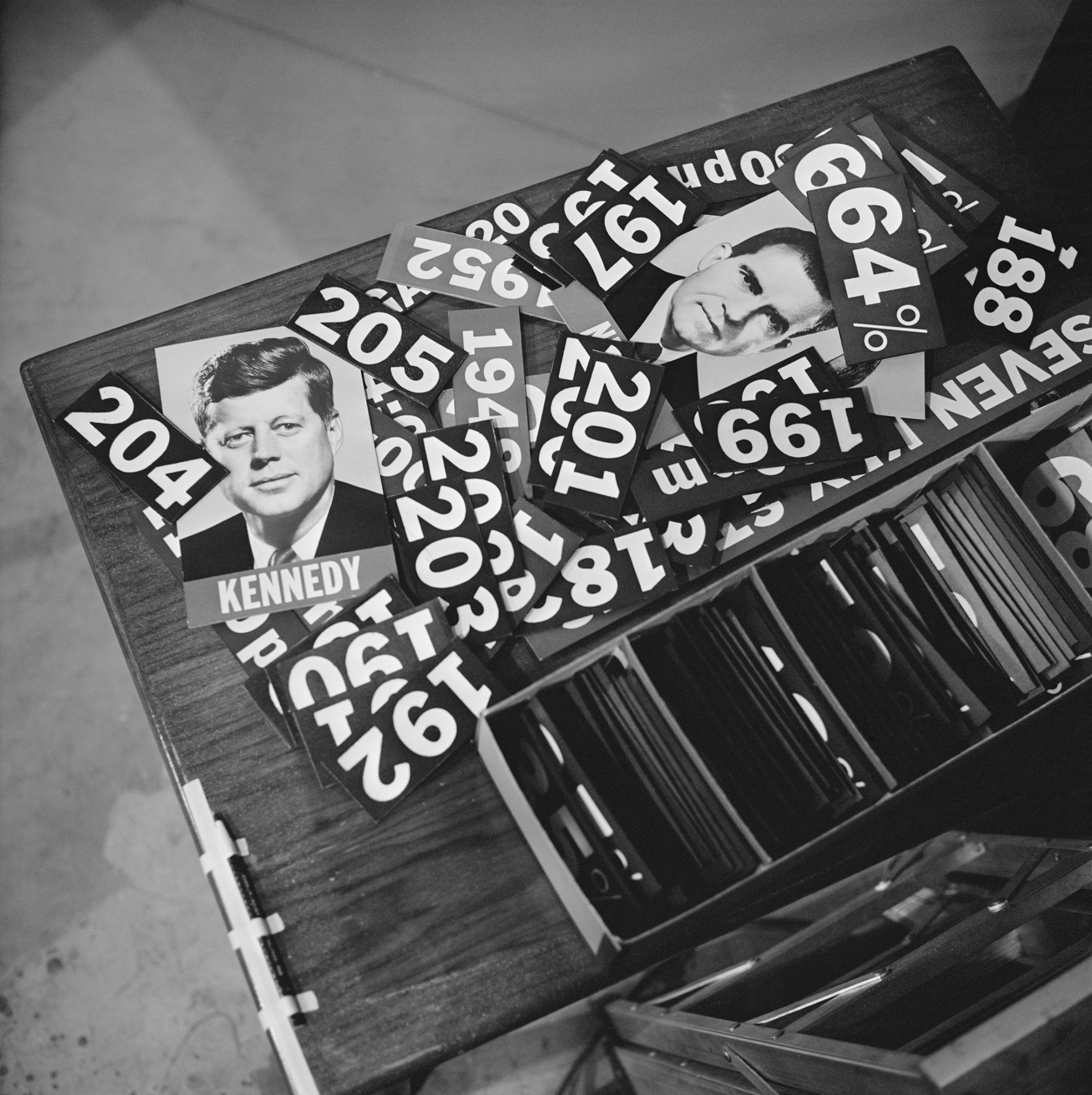

This has been the norm in America for more than a century. But in recent weeks it has become a point of contention, with Donald Trump claiming that the electoral system is rigged against him, that the media is in on the conspiracy and that he won’t necessarily accept the results–unless, he said with a wink, he wins. To bolster Trump’s claims, there are plenty of examples of media screwups, like when the Chicago Tribune called the 1948 election for Thomas Dewey over the real winner, Harry Truman. Or when the networks bungled the call in Florida in the 2000 presidential election, helping to fuel an electoral crisis.

That was then. Over the past 15 years, under increased scrutiny from Congress, the way in which the media gathers and analyzes voting data has morphed into a roughly $30 million tech-savvy collaboration that relies on more than 6,000 canvassers, reporters, data clerks and analysts as well as the most sophisticated statistical models of voter behavior in history.

It all begins at 6 a.m. on Election Day, when a polling company, Edison Research, dispatches the first of more than 1,000 surveyers to 933 randomly selected precincts across the country. Those surveyers spend all day asking as many as 100,000 voters to fill out exit-poll questionnaires on whom they voted for. The results are then combined with data from 16,000 phone interviews conducted with absentee and early voters. The AP, meanwhile, deploys 4,000 stringers to local government offices in every state to collect preliminary vote counts.

As Edison’s exit-poll data and the AP’s vote tallies roll in throughout the day, they are keyed into computer programs and checked against a ream of other data points, like historic voting patterns and pre-election polls, to identify statistical discrepancies. “We can see pretty quickly if a number looks off,” says Joe Lenski, executive vice president of Edison Research.

Much of this elaborate system is new. Until the early 1990s, most news outlets relied on their own polling and expansive reporting networks, as well as AP vote tabulations, to call winners. But in the mid-’90s, as newsroom budgets and staffs began to dwindle, some of the biggest outlets joined together to share the expense of collecting voter data on Election Day. The collaboration worked well, for the most part. But it ran into trouble in 2000, when the pollster it had hired to do exit polling, Voter News Service, circulated flawed data–and when, in the heat of election night, the networks got ahead of the AP’s vote count. Just before 8 p.m. E.T., they announced that Al Gore had won Florida, citing exit-poll data. By 2:30 a.m., with 85% of the vote counted, they reversed their first call, declaring that George W. Bush had carried the state and therefore won the presidency, prompting Gore to concede. By 4:30 a.m., the networks retracted their call yet again, as the AP’s vote tallies showed the Florida contest too close to call.

In the wake of that embarrassment, and under pressure from livid lawmakers, the five major news outlets–ABC, NBC, CBS, CNN and Fox News–vowed to do better. Along with the AP, they formed a new media consortium, the National Election Pool (NEP). They hired a new pollster. They pledged before Congress never to use their exit-poll data to characterize a state race before all the polls had closed. And they overhauled their entire Election Day reporting protocol.

Now, instead of sending exit-poll data directly to newsrooms, where there would be pressure to report it, NEP members create quarantine zones: two special rooms, in New York and Washington, where phones, computers and all other technology are banned. On Election Day, they’re filled with small teams of data analysts from each NEP member, who debate the validity of the data and correct for polling errors or shifting demographics. Just before prime time, the quants emerge to brief their outlets’ political directors and bureau chiefs, who then share the burden of making the hard calls. If the polls are closed with 85% of the vote counted and a candidate has a less than 10% chance of getting the votes needed to clinch victory, do you make the call–or do you wait until all the AP’s vote tallies are in, which can take all night?

Because elections tend to follow predictable voting patterns, many argue that these processes are overly wrought. But in an election where the fabric of our democratic process has been called into question, caution is in order, says Roger Tourangeau, president of the American Association for Public Opinion Research. “This time,” he adds, “they’ve got to be absolutely sure.”

For more on these stories, visit time.com/ideas

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com