As times change, so do labels. Back in the 1970s, those advocating for sexual or gender minorities often summed up the whole spectrum as “gay and lesbian,” never mind bisexual or transgender people. The acronym LGBT didn’t come into vogue until the 1990s, but like its predecessor, people have found those four letters too reductive. And so this acronym is about to go mainstream as a party of five.

Media advocacy organization GLAAD is releasing the tenth edition of its style guide, a language bible for journalists covering these issues, which asks that all major media outlets to use LGBTQ from now on. The “q” stands for queer.

“On one level, it is just adding another letter,” says Sarah Kate Ellis, GLAAD’s president and CEO. “But really it is bringing a whole new definition to the way we describe ourselves. It’s the start of a bigger shift.”

“Queer” existed as a slur for a long time, an arrow slung at people to make them feel like freaks or deviants. The oldest meaning, going back to the 1500s, is strange, peculiar or questionable, and the word will still ring pejorative in many older people’s ears. Yet around the time of the AIDS crisis groups really started to reclaim it (“We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!”), and today young people are increasingly gravitating toward this label, one with no precise definition related to sexuality or gender. Which is the point.

That shift Ellis refers to is one toward thinking about sexuality and gender in a more fluid way, as parts of our identities that are more complicated than any binary choice, multifaceted things that might evolve over time or be best described by a label that hasn’t even been invented yet. “Fluidity means just what the word is, that it’s ever flowing, and you don’t have to check a box or live within constraints,” Ellis says. “There is no limit to who you can be.”

Some see the word queer as an umbrella term, encompassing any identity that isn’t straight and cisgender. Some see it as a middle finger to the very idea that two options—man or woman, gay or straight—is sufficient for the natural variety of feelings that people have. Some see it as a tool for spreading the message that being inclusive, without needing all the details, is what it’s all about. “I see it as much more encompassing,” says Jeremy Charneco-Sullivan, a teacher in Missouri who previously used the label gay but now uses queer. His feelings about attraction haven’t changed, but his political ideas have: “I’ve grown to see the community as one united force.”

This chart from Google Ngrams shows the relative frequency of terms in published books. The latest date available for comparison is 2008.

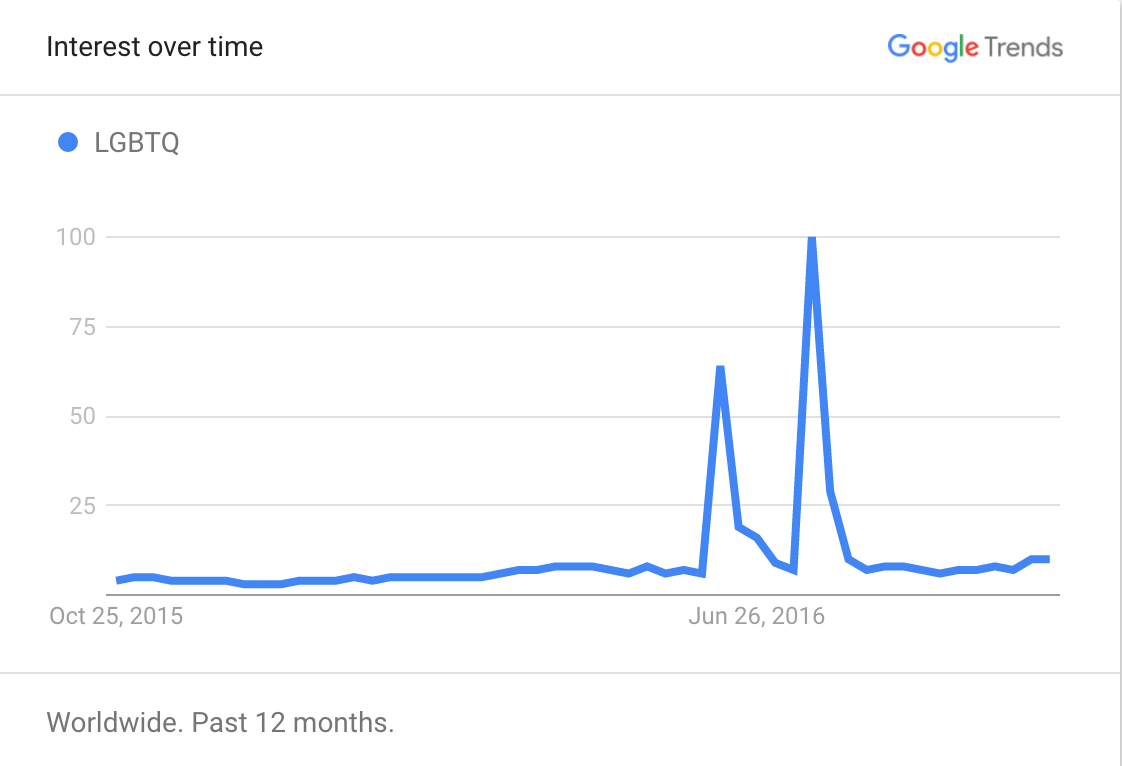

The word has been on the rise for the past several years, as has the acronym. Some media outlets are already using it, as are lots of advocacy organizations and even government programs. Teen magazines from outlets like Vogue are “going queer.” Liberal politicians are using the five-letter version, as are some Republicans. (Donald Trump used “LGBTQ” during his acceptance speech at the convention this summer. Twice.) When the National Park Service embarked on a mission to identify places of significance related to sexual and gender minorities two years ago, one of the first actions scholars recommended was changing the title of that mission from an “LGBT heritage initiative” to an “LGBTQ” one, so as “to have the initiative be explicitly inclusive of those who, for personal or political reasons, do not feel represented by lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender identifiers,” as the eventual report explained.

Adding that extra letter is a simple way to signal that you realize this business is complicated and don’t want to leave anyone out, even if you’re not part of that community or you don’t really understand what this shift is all about.

If five letters seem onerous, it’s worth noting that it’s more economical than longer acronyms out there, like LGBTQQIA: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual (or allies). Being exhaustive is nigh impossible, as new labels are born and spread in a minute. Facebook now allows users to input more than 50 different labels for their gender, including bigender, two-spirit and agender. Sexual orientation has just as many spins.

The deeper one goes into the layers of attraction, social relationships, gender expression and fantasies, the more categories there might be—if one gives them names. There could be a word for a person who identifies as a butch lesbian but is occasionally attracted to feminine men. Or maybe a person is mostly straight, a man who has been attracted to men but only wants to be in relationships with women. Maybe a person doesn’t identify as a man or woman and is only attracted to similarly non-binary people, yet doesn’t feel sexually attracted to anyone unless they’ve formed a deep emotional bond. Young people, hyperindividual Gen Zers, are exploring those permutations. Maybe the underpinnings are social, maybe biological, maybe rebellious, maybe open-minded.

“It’s so difficult to really know things empirically,” says Cornell psychology professor emeritus Ritch Savin-Williams, “because a lot of the research only provides these three or four boxes. And a person will say, ‘Well, hmmm, I guess if I have to choose one, I guess I’ll choose straight’ … If you had more options, you’d see the complexity.”

Other changes to GLAAD’s style guide underscore this theme that four letters is just the ABCs. It’s the first in which the section on covering the bisexual community includes the more open-ended label “bi+.” There are inaugural glossary definitions for “intersex” and “asexual.” Journalists will find the descriptor “non-binary” alongside the explanation of what it means to be “genderqueer.”

GLAAD’s guide also notes that some prominent media outlets currently tell their journalists to use LGBT, characterizing the four-letter version as a rather cumbersome acronym to be used sparingly. But there is change afoot. The AP Stylebook lists LGBT as the first recommendation, but has noted since 2014 that LGBTQ is “acceptable.” And the people at GLAAD believe that their style guide’s update will cause a “ripple effect.” This is the kind of matter that the organization exists to weigh in on.

“It’s time,” says GLAAD’s Ellis. “It’s the direction of the future.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com