In China last week, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte announced his military and economic “separation from the United States.” America “had lost,” he said to applause in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People.

Duterte’s beef with the U.S. spans historical atrocities and picayune slights — such as being denied a visa to visit his college girlfriend. Here is some more of the shared history that has shaped U.S.-Philippine relations

1. The Moro Massacre

When Obama nixed a meeting with Duterte on the sidelines of last month’s ASEAN summit, the international press focused on how POTUS would take being called a “son of a whore.”

Lost in the furor, though, was Duterte’s big swing: the U.S., he said, hadn’t apologized for the 1906 Battle of Bud Dajo, in which American soldiers slaughtered as many as 1,000 Moro — Philippine Muslims — holed up in an extinct volcano.

More recent atrocities have been committed against the Moro. Under dictator Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled from 1965 to 1986, soldiers and state-sponsored paramilitary massacred hundreds of Moro.

However, Richard Chu, an associate professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who specializes in Philippine colonial history, tells TIME that by being selective about the atrocities he recounted, Duterte would “be able to at least get the attention of the U.S. government, hopefully resulting in more equitable treatment.”

2. 300 Years in the Convent, 50 in Hollywood

The Philippines became the first U.S. colony after Spain ceded the islands for $20 million in 1898. Then began a process U.S. President McKinley described as “benevolent assimilation.”

Aileen Baviera, a professor of political science at the University of the Philippines Diliman, tells TIME that U.S. colonialism is viewed much more positively than Spanish colonialism because of its contributions to public health, education and political structure, but that negative aspects related to war and repression had been muted “in large part because the early discourses were shaped by the Americans themselves through media and public schools.”

Baviera added that today Filipino historians were more cognizant that “American colonial policies supported traditional elites and feudal social relations that continue to form the basis of today’s oligarchy.”

But colonization impacted Filipino popular culture too: a popular maxim is that the country was shaped by 300 years in the convent and 50 years in Hollywood.

3. Hoop Dreams

Basketball began to spread through the Philippine school system and YMCA soon after the Americans arrived, and the country is home to the second oldest basketball association in the world, as well as Asia’s first professional basketball league.

Today basketball remains a national pastime from the DIY courts in Manila slums to the annual university game between the two great rivals Ateneo and De La Salle. In January this year, the nation mourned after Caloy Loyzaga, regarded as one of the Philippines’ all-time greats, died at the age of 85.

The only time basketball is superseded as the national sport is when Manny Pacquiao fights. “Pac-Man” is so popular that according to the Philippine National Police, the crime rate in the country drops dramatically during his matches. The boxer turned Senator has even been tipped to make a presidential run in 2022.

4. Dreaming of the American Dream

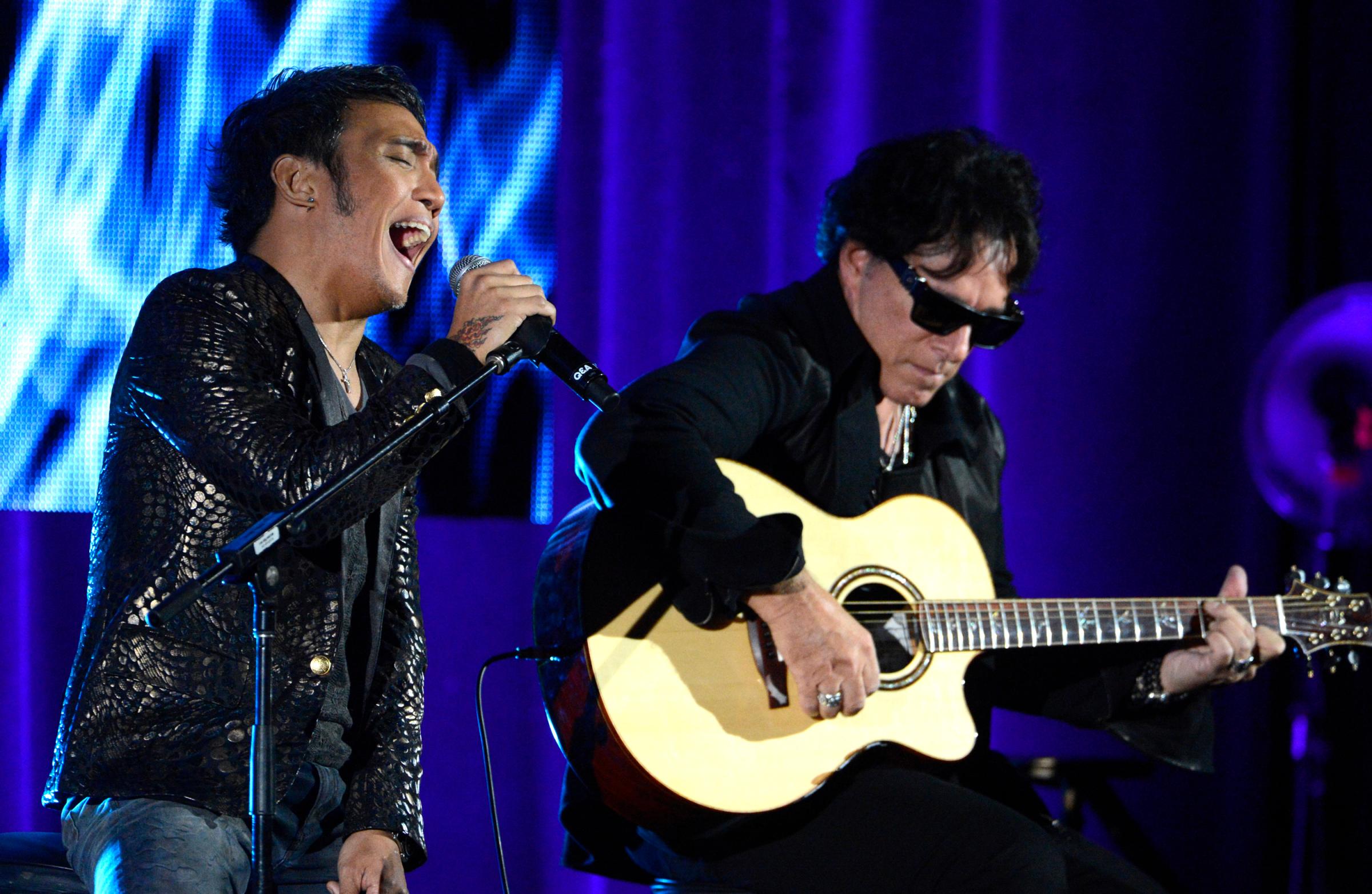

When American rock band Journey lost their lead singer in 2007, they scoured the Internet for a replacement – and found Filipino singer Arnel Pineda.

Made homeless after his mother died, Pineda had been forced to drop out of school as a teenager and take up odd jobs collecting scrap metal and selling newspapers. Journey guitarist Neal Schon discovered Pineda years later, after a series of videos were posted of him covering American songs, including the famous hit, “Don’t Stop Believin’.”

“It’s like 12 o’clock at night,” keyboardist Jonathan Cain says in a documentary made about Pineda. “Neal calls me. I found this kid on YouTube. It’s in Manila. I get online in the office. I look, I listen. I call him back. Kid can sing. Great voice. Unbelievable. But can he speak English?”

Pineda reportedly had to swim against an “undercurrent of racism” from some Journey fans but is widely regarded as a hero who came from the streets to break America.

Filipinos “dream of living the American dream,” Diana Roxas, an advertising executive with Philippine media conglomerate ABS-CBN, told TIME. “We live in an Americanized culture where most people consider the U.S. the land of milk and honey.”

5. Defense Cooperation

The U.S. maintains the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement with its former colony and backed the Philippines’ Hague tribunal result, which contested Chinese territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Even after Duterte announced that this year’s joint drills would be the last, the military machine rolls on: when the U.S. formally turned over the second of two C-130 planes on Monday, Philippine air-force chief Lieut. General Edgar Fallorina told ABS-CBN the acquisition reaffirmed “the strong partnership between our two countries.”

But military ties have been a source of tension too. After 2006’s Subic rape case and the killing of 19-year-old Filipino Jennifer Laude in 2014, the U.S. invoked the Visiting Forces Agreement, which activists denounced as giving “special treatment” of U.S. personnel in relation “to second-class Filipino citizens.”

And while the President was in Beijing last week, activist Renato Reyes led a protest against U.S.-backed mining companies and plantations that, he tells TIME, had encroached on indigenous people’s ancestral lands and against “a U.S.-directed counterinsurgency program, which has caused militarization of many communities.”

6. “Haunted by Ghosts and Movie Lovers”

In her collection Danger and Beauty, Philippine-born U.S.-based poet Jessica Hagedorm describes her homeland as a “landscape haunted by ghosts and movie lovers.”

The silver-screen celebrity carries political clout in the Philippines, whose impeached President Joseph Estrada was a movie actor before he took office. Even the President’s nom de guerre, Duterte Harry, has Hollywood pretensions.

And perhaps the TV screen does too: according to polling data released this month, among Asian-American voters, Filipino Americans are the biggest supporters for reality-TV star turned GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump.

Around 4 million people of Philippine ancestry currently live in the U.S. Most live in Hawaii and California, where they constitute the largest Asian minority group and are a legacy of the laborers who worked the fields and canneries of the West Coast in the early 1900s.

The connections between the Philippines and the U.S. run deep, and have sometimes been fraught, but would be very difficult to cut.

Last Friday, the Philippine National Police announced that they would distribute Obama-themed Halloween masks as part of a public information campaign.

On the same day, on his return from Beijing, Duterte “clarified” that he could not sever ties with the U.S. because “the Filipinos in the United States will kill me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Joseph Hincks at joseph.hincks@time.com