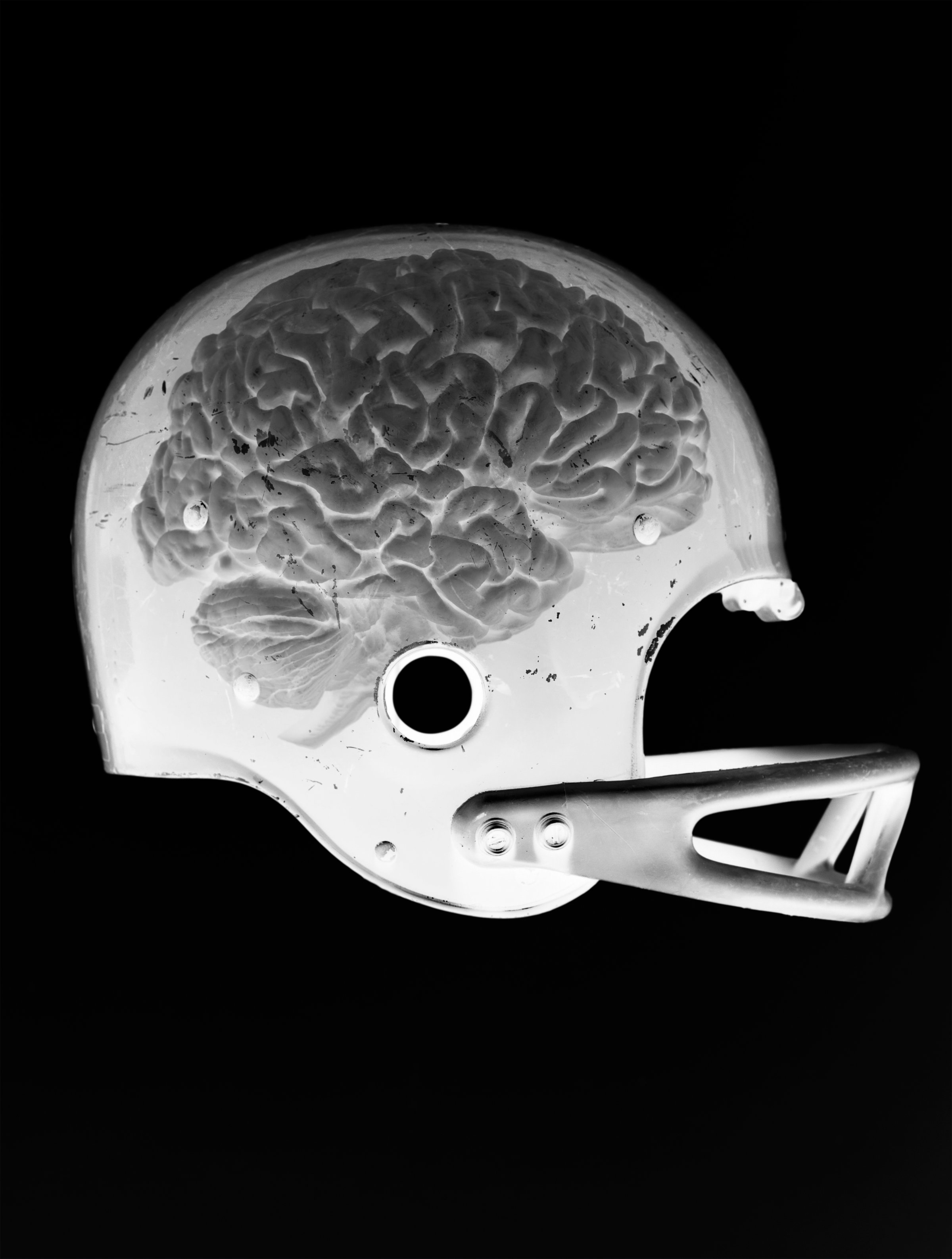

Research is mounting that concussions have devastating impacts on professional football players in the NFL—and the symptoms don’t happen overnight. The bad effects from concussions can continue years after the trauma, and brain experts say that damage to delicate neurons can also accumulate over time, even with repeated head injuries that don’t reach the level of concussion.

That’s why Dr. Christopher Whitlow, chief of neuroradiology at Wake Forest School of Medicine, and his colleagues investigated brain changes in young players. Whitlow wanted to better understand how non-concussive trauma to the head, the kind caused by normal football play, affects the brain. In a study published in the journal Radiology, his team reports that although these changes are subtle, they are visible in the brains of young players.

The study involved 25 boys between ages eight and 13 years who played a single season of football. The players agreed to wear special helmets that tracked impacts to the head and had MRIs done at the beginning and end of the season to note any differences resulting from their season of play.

Whitlow found that the more impacts a player had to the head, the more changes in a part of the brain called white matter, which is made up of insulated neurons that form the basis of communication between different parts of the brain. Such changes are concerning since the white matter of the brain is still developing and evolving during this age, and changes to its normal trajectory might have lasting effects on many aspects of brain function, from cognition to personality to behavior.

For now, it’s not clear what these changes may mean, or whether they have any impact on thinking or development. “There’s a lot we don’t know about the changes,” says Whitlow. “We don’t know if they persist. We don’t know if a couple weeks after the season ends, they go away.”

The differences are so subtle that if a brain expert were to look at the MRIs of the players after the season ended, they would not necessarily identify them as having experienced brain trauma. The changes are only evident when compared to the original brain scans.

Whitlow is following some of the players for a longer period of time to see if continued play for additional seasons increases the changes, and whether these changes start to impact their cognitive functions. He’d like to follow more players for five years to better understand the impact of these white matter alterations.

For now, he says, the results shouldn’t discourage children from being physically active, or even from playing football. But, he says, “we should do simple things now to protect children, like knowing the signs and symptoms of concussion and teaching them to children, so if they are injured on the field, they can get help from health professionals right away.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com