Sarah Miller writes for The New Yorker, The Hairpin and other publications

Ian Wickerman opened his eyes to yet another grim, underpaid, unappreciated day as an adjunct professor of poetry at Bixley State University. Brightening somewhat at the idea of grinding up some single origin El Salvadoran and making himself a triple ristretto cortado he used the scant energy provided by this thought to ascend from his bed.

His wife Danielle was still in bed, sitting up, red pen in hand, a pile of student papers on Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now before her. “That must be a really interesting book to be teaching right now,” Ian said as he put on his corduroys and a threadbare cashmere sweater given to him by the very rich girlfriend he had, in retrospect, stupidly dumped for Danielle, because Danielle had (at the time) thought he was brilliant. “Have any of the students noticed how Melmotte is a smart version of Donald Trump?”

Danielle snorted. “No, but I made the mistake of pointing it out to them, and five of my papers—wait, no, seven—are titled “Why Melmotte is Legit.”

“Ah, youth,” said Ian, picking up his phone from the bedside table. Usually he had a message or two, but today, he had over twenty, Facebook, texts, emails, all from fellow poets. He wondered: Had Sharon Olds become a Seventh Day Adventist? Had Eileen Myles become engaged—to a man?

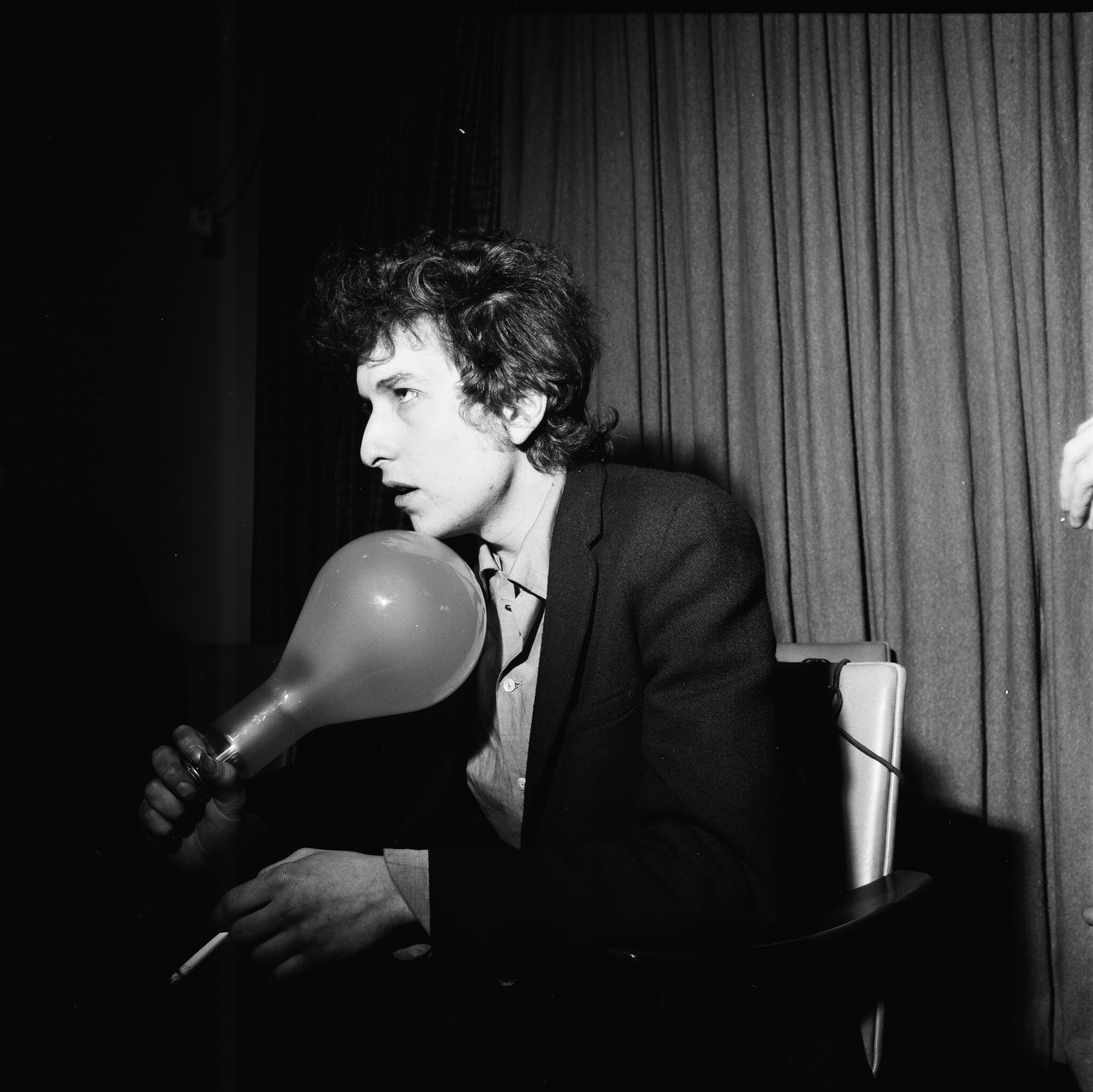

The news was indeed surprising, but it was wonderful. Bob Dylan—his hero, his muse and, last but not least, the subject of his 2003 dissertation “Don’t Follow Leaders, Watch the Parking Meters: The Songs of Bob Dylan and Vladimir Vysotsky”—had won the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Tears sprang to his eyes. He tried to speak but found he could not.

“What happened?” Danielle said, alarmed.

“The most wonderful thing! Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for literature!”

“Oh,” Danielle said, “I thought it was something exciting, like, I don’t know—like you found out Claudia Rankine did a Target ad.”

“This isn’t exciting?”

Danielle pressed her lips together. “Sorry to be a wet blanket,” she said. “And I know it’s cool now to think everything is everything else, etc. But literature and songwriting are not the same thing. They’re totally separate. Plus, I mean—someone gave a big award to a rich white man. Alert the media!”

She went back to her papers.

Ian walked down the hall without saying a word. As he passed his eleven-year-old son Cash’s bedroom, Cash called out, “Hey Dad, that weird, ugly, short guy who wears ugly jackets and makeup won something.” Ian did not say anything. He made his cortado and drank it. He jotted down a few lines “savory and savored notes of earth/bright floral sky/nutty liquid songbirds/oh coffee easing me to consciousness.”

Once out the door he called his brother, Nick, a public defender in Pittsburgh. “Hey, Nick,” he said. “I know this isn’t your area of expertise, but do you think I could get divorced for less than 200 bucks? No, it’s ok, don’t be upset. Whoa, what? Oh my God—what? Your client actually said those words—“I like Dylan, but I don’t know if I’d call songs literature?” Buddy. Wow. Absolutely you did the right thing walking out right before court started! ‘Have fun defending yourself on the mail fraud charge, a-hole! No, no. Danielle and I don’t have any property. Do I want custody?” He paused and watched his feet as they took the steps into Sam M. Walton Hall. “Nah.”

Adjuncts were only allowed use of the department copy machine between 9:15 and 9:22 every morning, so he was relieved to see it empty. He needed to print out 100 copies of the lyrics of “I And I”, an overlooked gem from Dylan’s 1983 album Infidels, as well as a short biography of the album’s co-producer, Mark Knopfler. He smiled wistfully, imagining a student evaluation: “Professor Wickerman introduced us to visionaries like Bob Dylan. Also when I think of how very few of my generation will know who Mark Knopfler is, I shudder and thank Professor Wickerman that I will not be among them.”

“Good mood?” Russell Lytton, another adjunct, himself a poet, stood there with a copy of Mark Doty’s Atlantis under his arm.

“Pretty cool about old Bobby D,” Ian said.

Russell made a face. “I don’t know,” he said. “I feel like if we let the definition of poetry arbitrarily expand…”

At the word arbitrary, Ian felt ire rising up from his feet into his guts and his head. The copy machine chugged away, and he kept seeing the words “originally a member of the band Dire Straits” over and over again, in a way he felt mocked him. “But he won for literature, not poetry.”

“I’m well aware,” Russell said, slipping his own selection—which, though Ian found much to admire in, he found well, rather expected—into the machine. “Still, I think that music is not poetry and while, I get it—you know, all of my work is about intersectionality, and in a way, saying songs are literature is, if you will, an intersectionality of poetics, right, so…”

After Ian had disposed of Russell’s body in a Dumpster behind the dining hall, he went to teach his class. He handed out the “I and I” lyrics, explaining that today was a very exciting day in American letters.

“Wait, since when are we are going to be writing letters,” one of his students whined.

“That’s not on the syllabus,” someone shouted. “We want our money back.”

“Letters just means literature,” Ian said. “And poetry is literature. And today Bob Dylan won a Nobel Prize!”

One of the students raised her hand. “Why would a singer win the Nobel prize? Did he do something for world peace?”

Ian explained that there were a lot of Nobel prizes. “There’s one for peace, but there’s also medicine, there’s one for economics, there’s one for physics, and chemistry…”

“If there are so many of them,” someone shouted, “Then why is this Dilweed dude winning one such a big deal?”

* * *

Back at home, he wasn’t at all surprised to see a note from Danielle saying she had left him for Carissa Von Shasta, the chairman of the college’s brand new Digital Humanities department. The house was empty, save for his records, the stereo and his AeroPress. She had also left one folding chair. Ian sat in it and was googling “teach English in Kuwait” when there was a knock on the door.

It was two policemen, a man and a woman. The woman spoke. “Yes, we are inquiring about the death of Professor Russell Lytton. We have a report that the two of you were chatting at a college-owned Xerox machine earlier today.”

He had forgotten all about this. Trying to think of the right thing to say, he stalled for time. “I am pretty sure the machine was actually a Ricoh… I mean, for your report.”

She looked at her partner and sighed impatiently. “Professor Russell Lytton is dead. We have a report that earlier today, you and Professor Lytton were seen arguing about the validity of Bob Dylan’s recent Nobel Prize for Literature, an argument that I personally can see both sides of…”

Ian felt the hairs on his neck stand up, but he had to remember to keep his cool. “Excuse me, officer, did you say Professor? Because Russell Lytton was an adjunct.”

She and her partner exchanged looks and then conferred for a moment. She was writing something on a pad. Ian craned his neck to get a look and saw that she was crossing out the words “Professor of Literature” and replacing them with the words “Poetry Adjunct”. She then crossed this out and wrote a question mark, and the words “Oh well.”

She nodded to him. “Thank you so much for the information. I think we can wrap this one up.”

Ian watched them drive away. Back in the apartment, he took Infidels out of its jacket and was just about to put in on the turntable when it occurred to him he wanted to hear something more celebratory. He really hoped he hadn’t sold Weezer’s debut album, Weezer. He hadn’t! He put on “Undone (The Sweater Song)”, made himself another triple ristretto cortado and screamed the lyrics out into the empty space late into the night.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com