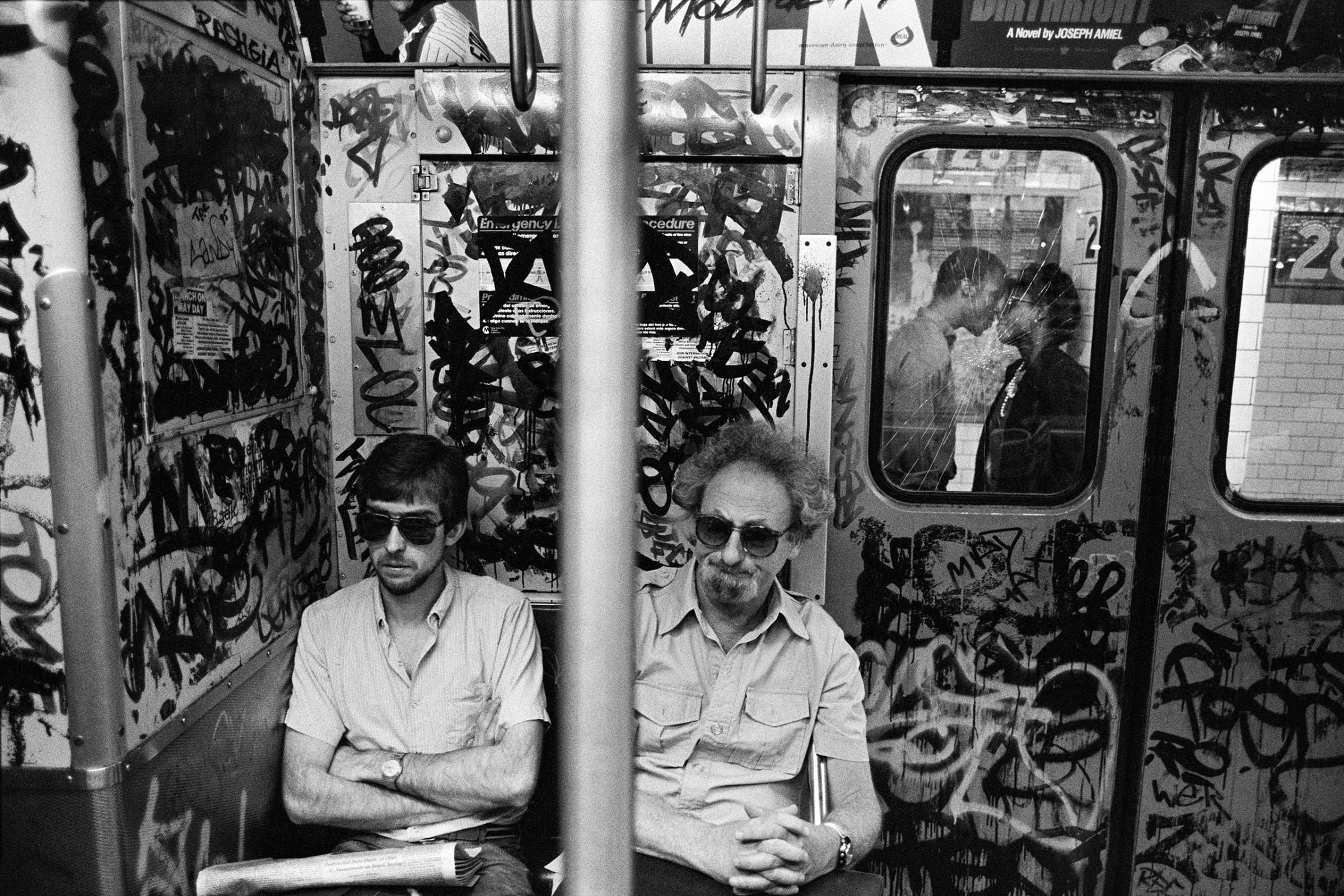

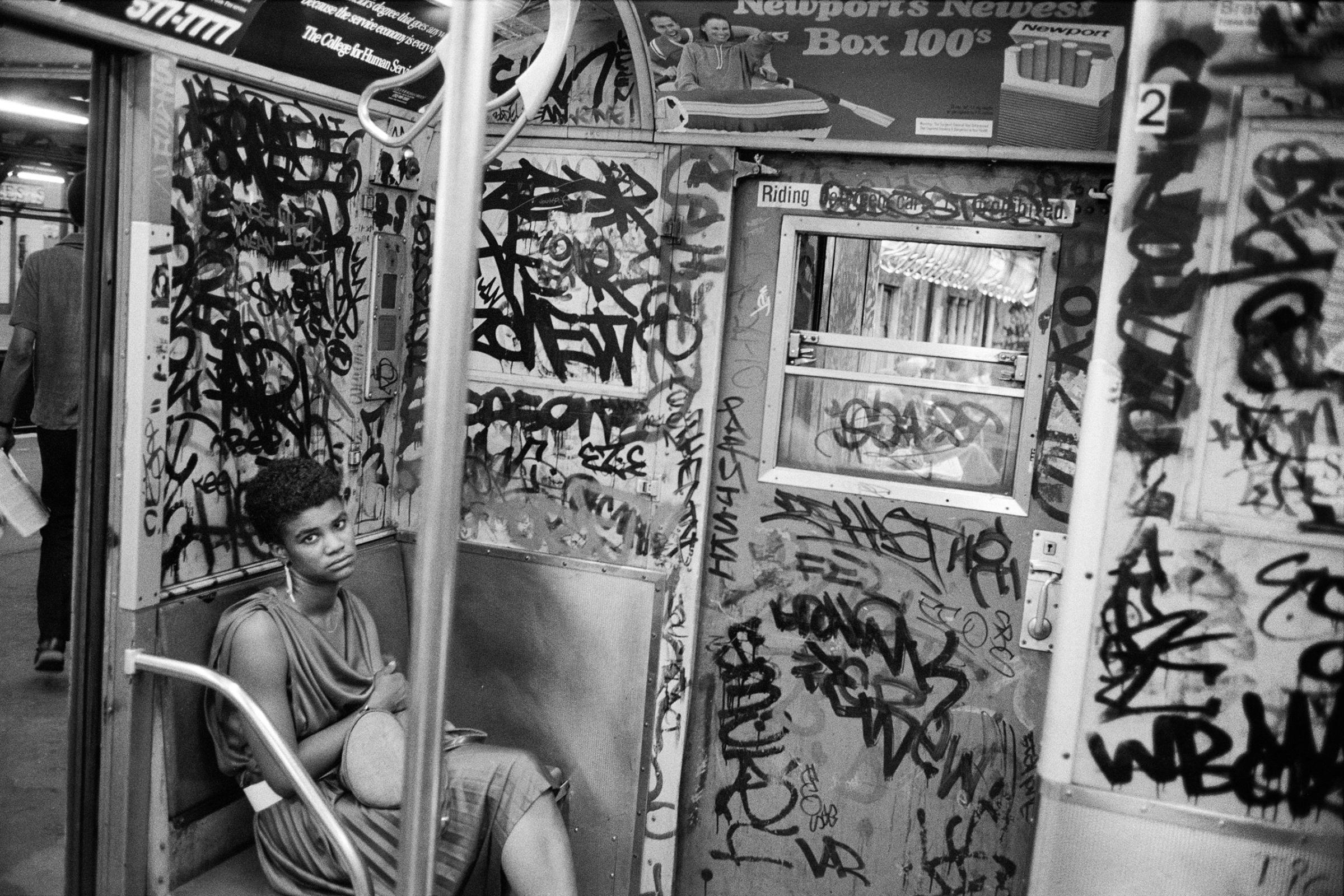

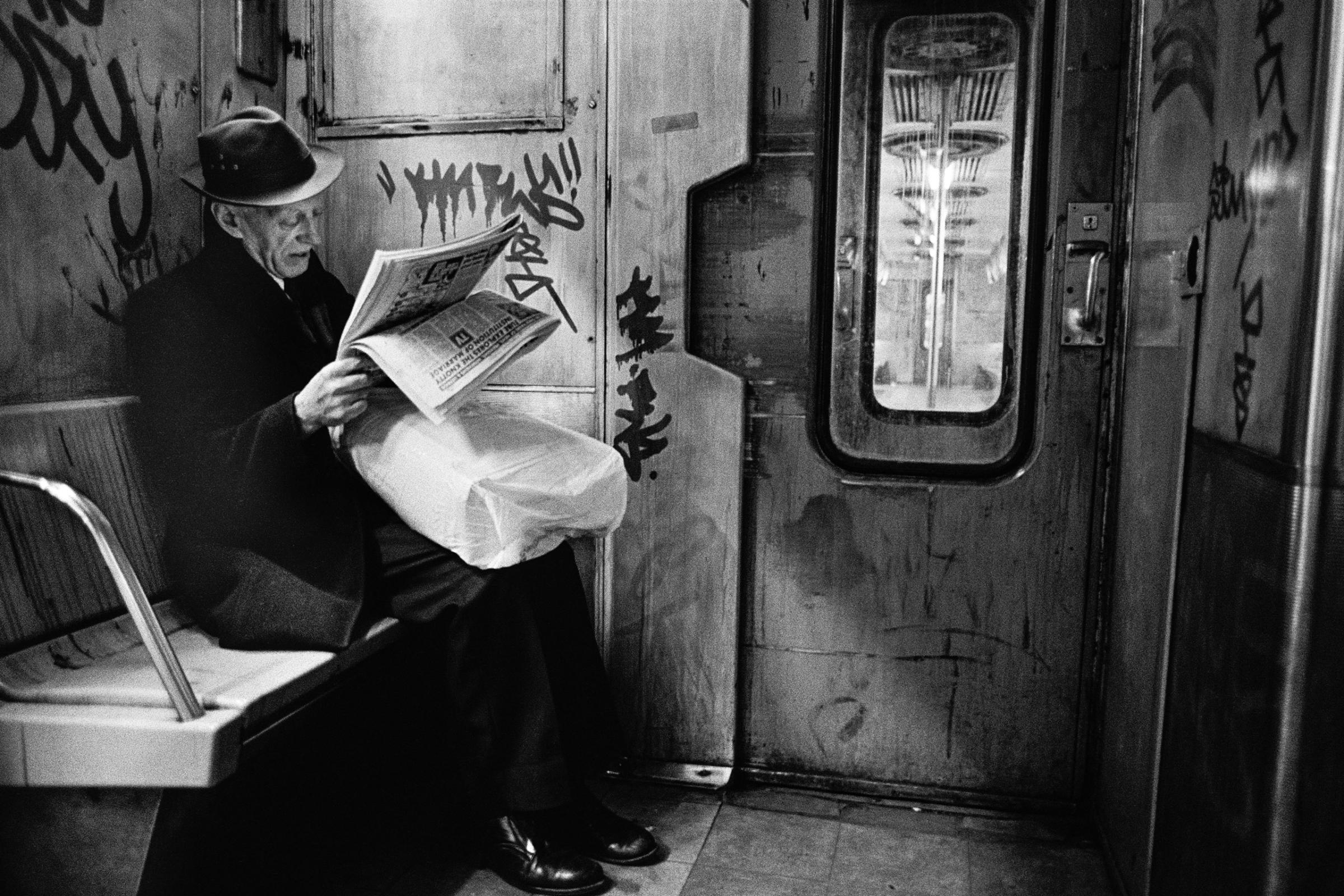

To view Richard Sandler’s photographs is to look into the soul of a broken New York. From the pages of his new book, you can almost hear the rattle of the subway cars, the tap of high heels on concrete and the commotion of midtown rush hour. But if the city is the theatre, it’s the people who take center stage.

The Eyes of the City is Sandler’s first retrospective in print. It’s an impressive collection, mostly taken between 1977 and 1992 on the streets of New York, with several also in Boston. The title’s meaning is two-fold: while it’s the eyes of a skilled photographer who captured the scene, the eyes of the subjects are just as crucial in formulating the magic potion that creates great street imagery.

“It seemed to me that the unifying, ongoing theme of the book was that it was about eyes. It was about looking,” Sandler tells TIME. “It’s about getting photographs where either people are looking in a penetrating way at me or looking at something else in a very interesting way that maybe poses a bunch of questions. So it is my eyes; I’m seeing these things. But it’s a two-way street and two kinds of pictures.”

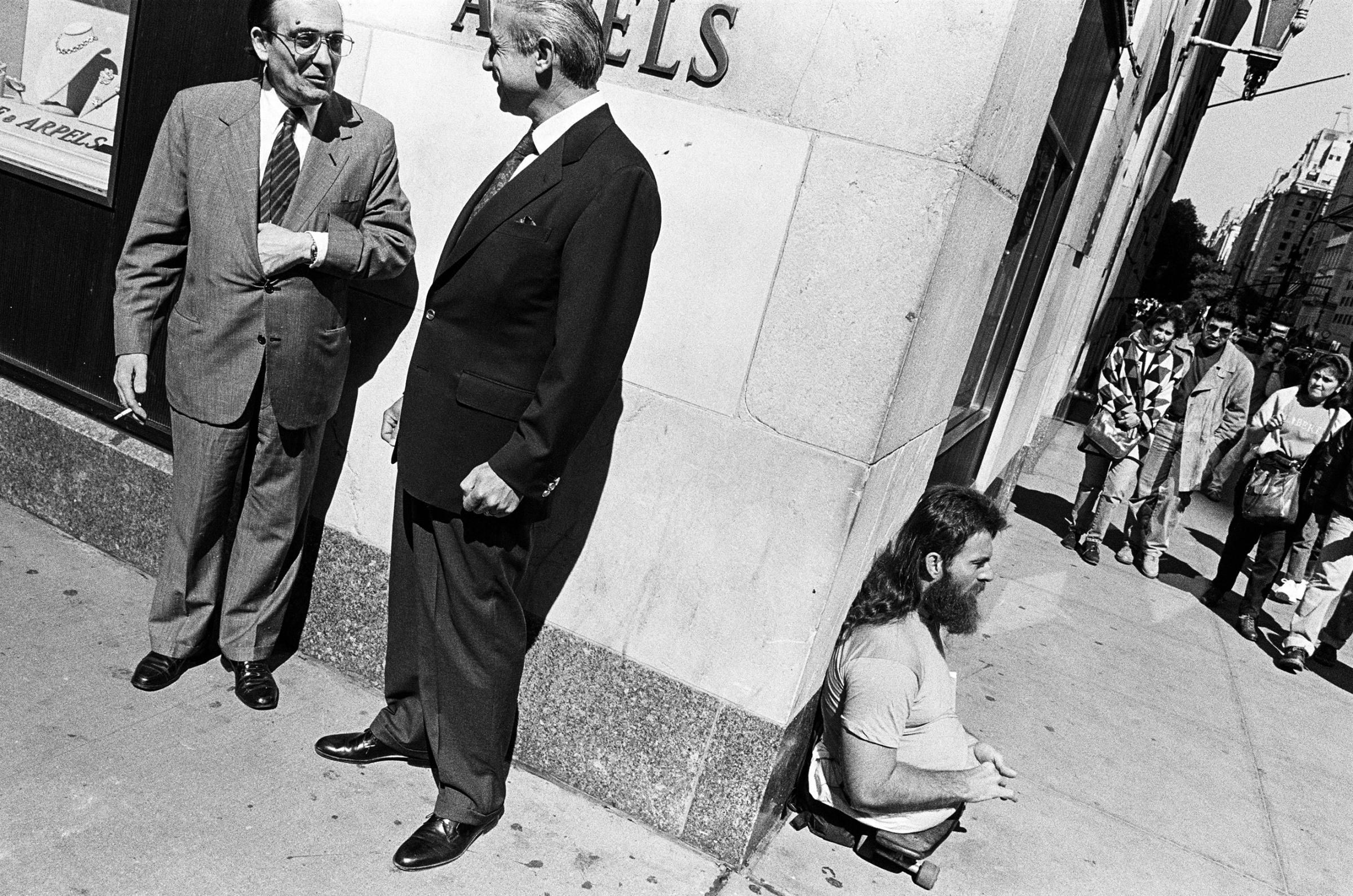

Sandler’s New York of the late 70s and 80s is a cyclone of faces, furs and filth. It’s a visceral cross section of fabulous wealth and terrible misfortune, often found in the same frame. A homeless man on his knees, hands to the heavens, as a truck drives past with the word ‘Security’ on its side, is just one example. Through his photos, Sandler elevates these fallen characters, pulls them out of the dirt and makes you examine them and in doing so, immortalizes their struggle. “I guess I believe in the remedial power of art,” says Sandler. “Because with street photography, with this body of work, I’m definitely implying a lot of things and hopefully making people aware of some of the political realities on the street.” More than calling into question this disparity, Sandler hopes it gets under the viewer’s skin “like a beetle that bores into your brain.”

But to capture these almost absurd moments of paradox “you’ve got to have your camera out and ready and focused.” A perfect street shot is a magical thing but it’s also the product of hours of stalking and second-rate B-roll. “That’s one of the reasons shooting analogue is great,” says Sandler. “It’s wonderful to have all the failures because in each of them are little jewels, little bits of things that are really amazing, and with them you build up a visual vocabulary.” There is light in the shade, of course, and littered throughout the powerful statements on class and capitalism are moments of delightful humor.

His photographs also speak truth as plain fact, with no double entendre implied. Sandler, quoting Garry Winogrand, says: ‘”There’s nothing more mysterious than a fact clearly described.’ So that’s another kind of photograph; that doesn’t try and do anything but show you exactly the way something looks. But by virtue of it being a photograph, it is absolutely different from life.”

Sandler has always loved photography but it became his obsession after moving from New York to Boston to work as a macrobiotic chef in 1968. He later began boarding at the house of Mary and David McClelland, an eminent motivational psychologist and Harvard professor. It was Mary who gave Sandler her Leica 3F in 1977 and taught him how to develop film in their basement darkroom. “And so I just hit the streets and started shooting,” says Sandler. It was a golden situation for a young creative; rent was cheap and the weekly dinner guests read like a who’s who of prominent 70s intellectuals – from Buckminster Fuller to John Cage to Gregory Bateson.

He credits his love of street style with his childhood spent wandering his home city. “I just loved being out on the streets. I grew up in 60s New York where the world was on parade. Everything happened on the street. There was an irresistible force that had everybody trying to be the best they could be.” He adds: “Street photography is a wonderful endeavor because you’re looking for things that are actually going on but at the same time, there’s that frame. That arrangement of shape, just formally, is in itself so compelling.”

The work that first enchanted him was that of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Andre Kertesz and in particular Thomas Roma’s pictures of Brooklyn backyards. “It was the first tickle,” says Sandler. “Seeing these incredibly-put-together pieces that get under your skin in ways that you can’t understand… They get in through a door that you’re not guarding.”

Sandler’s work has arguably never received the recognition it deserves. During John Szarkowski’s reign over the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art between 1962 and 1991, he championed the work of Diane Arbus, Gary Winogrand and William Eggleston – but Sandler was left out in the cold. He met with Szarkowski once, while presenting his work to the institution. Szarkowski told him his photographs were good but in the same breath said he “hoped he would receive the recognition he deserved by the time he was 70.” Sandler turns 70 in two months.

“As far as the world of so-called art photography, I wasn’t allowed in, no matter what. I wish I had gotten some support for my work, but I’ve gotten none,” says Sandler. “But I never stopped. I just kept on shooting.” It wasn’t really until the birth of social media and the burgeoning of the web – and with that a more level audience – that Sandler realized he did have a strong following. And while he may have mixed feelings about what he dubs the “fauxtography” era, it has allowed his voice to be part of the contemporary conversation.

The book has come out nearly 25 years after the bulk of the photographs were taken, but that distance has given Sandler pause for reflection. “I’m glad I took this long. All of the projects in my life have taken a long time,” says Sandler. “The longer a project takes, the deeper it gets.” Though he still carries his Leica everywhere he goes, these days Sandler prefers moving image to street photography, something he took up in the early 90s, producing a series of free-form documentaries including The Gods of Times Square and Brave New York. “It was kind of a seamless transition. I just fell in love with it,” explains Sandler. “I’m a filmmaker now but I’m still trying to make interesting imagery, which of course I learnt from photography.”

Sandler’s careers as a macrobiotic chef, acupuncturist, photographer and filmmaker have all come from the point of view of healing, and he hopes that The Eyes of the City, will in some way help repair the city’s wounds, still gaping years on. The photographs document up until 2001, just months before the September 11 attacks. For Sandler, this felt like a good place to end. “Because after 9/11, most people at least that I knew were asking the question: ‘What did we do to deserve this?'” He says. “That was so healthy. There was a moment of reflection and pause. So this is a look at the world before 9/11.”

Richard Sandler is a photographer and filmmaker based in Upstate New York. The Eyes of the City is available now to pre-order. There will be a book signing at The Half King, New York, on Nov. 6. Follow him on Facebook.

Kira Pollack, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s director of photography and visual enterprise.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com