It’s been about 150 years since the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted black people the right to full citizenship, but some have recently questioned whether the Constitution applies equally to all citizens. Specifically, in the wake of the death of Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, N.C., some—like Eugene Robinson, writing in the Washington Post—have questioned whether “Second Amendment rights are for whites only,” as the matter of whether he had a handgun ought to be made moot by North Carolina’s being an open-carry state. This is not the first time the question has been asked in recent months: Erica Evans asked the same question in the Los Angeles Times in July, after the police-shooting deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile.

But, while the question has recently returned to headlines, it is in fact as old as the country itself.

Gun restrictions in America date back to the colonial era when the settler class, engaged in violent conflicts with the indigenous population, initiated laws in 1611 against American Indians owning guns. By 1640 gun restrictions were expanded to include “Negroes and mulattoes.”

After the American Revolution, the fear of disarmament was widespread, particularly among southern whites who feared they would be left vulnerable in a slaveholding south. As Constitutional law expert Carl T. Bogus has argued, James Madison wrote the amendment as a guarantee to his constituents in Virginia and to the south at large “that Congress could not use its newly-acquired powers to indirectly undermine the slave system by disarming the militia, on which the South relied for slave control.”

To the contrary, the founders justified the forced disarmament of slaves, freed blacks and mulattoes for fear of insurrections. Slave codes were enacted and enforced by slave patrols, which comprised armed militias, to ease white fears of black violence. As Bogus noted, “Slavery was not only an economic and industrial system, but more than that, it was a gigantic police system.” Notwithstanding, Virginia passed a law in 1806 allowing free Negroes and mulattoes to own guns with the approval of local officials; but in the aftermath of the 1831 Nat Turner rebellion, the Commonwealth repealed the law and prohibited the sale of guns to free blacks.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

During the 1840s and 1850s, abolitionists such as Lysander Spooner of Massachusetts, Joel Tiffany of Ohio and Rev. Henry Ward Beecher (the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe) of Kansas supported gun ownership for blacks for the purpose of self-defense against southern tyranny. Beecher, who believed the gun rather than the Bible would overturn slavery, expressed in the New York Tribune in 1856, “You might just as well read the Bible to Buffaloes” as those who support slavery only revere “the logic that is embodied in Sharp’s rifles.”

Soon after, however, the Supreme Court stepped in.

In his March 1857 opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney stated that blacks are “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” These are the most quoted words from this infamous decision, which determined that blacks, slave or free, were not citizens of the United States and therefore not entitled to equal protection under the law. Taney maintained that black people were governed by “the operation of a special set of laws” and “police regulations . . . necessary for their own safety.” As such they were denied Constitutional rights like freedom of speech, freedom of movement, the freedom to assemble—and the right to bear arms.

To put it bluntly, the Second Amendment (and the entire Constitution) did not apply to black Americans.

After the Civil War, Radical Republicans in 1866 passed the Freedmen’s Bureau Act and the Civil Rights Act, guaranteeing the right of freedmen to bear arms for self-defense. Yet, the fight to keep guns out of the hands of blacks continued. As historian Gerald Horne has claimed, after the Civil War “a good deal of the battles of the bloody reconstruction period, circa 1865 going forward, [were] about keeping arms out of the hands of black people.”

Leading the charge to disarm the freedmen was the Ku Klux Klan, organized in Tennessee in 1868. The group’s primary objective was gun control. Chapters of this vigilante group soon emerged all over the South to assume the role of the former slave patrols in maintaining law and order (i.e. white supremacy). The goal of the Klan was to completely disarm blacks of all guns and ammunition acquired during the war. The Klan’s reign of terror persisted throughout the Jim Crow era.

While the South spent a century in its effort to keep blacks unarmed, another campaign to accomplish the same aim began in California in the 1960s. By 1963, as many blacks grew disillusioned with the unfulfilled promises of the Civil Rights Movement, paramilitary organizations such as the Black Panther Party for Self Defense emerged in Oakland, to resist the terror of police brutality which was a daily reality in black communities throughout the nation. The Panthers turned urban policing on its head with the mantra “policing the police.” They strolled through the streets dressed in black attire accessorized by bandoliers and rifles observing police arrest from a legal distance to insure that an arrestee’s legal rights were not violated.

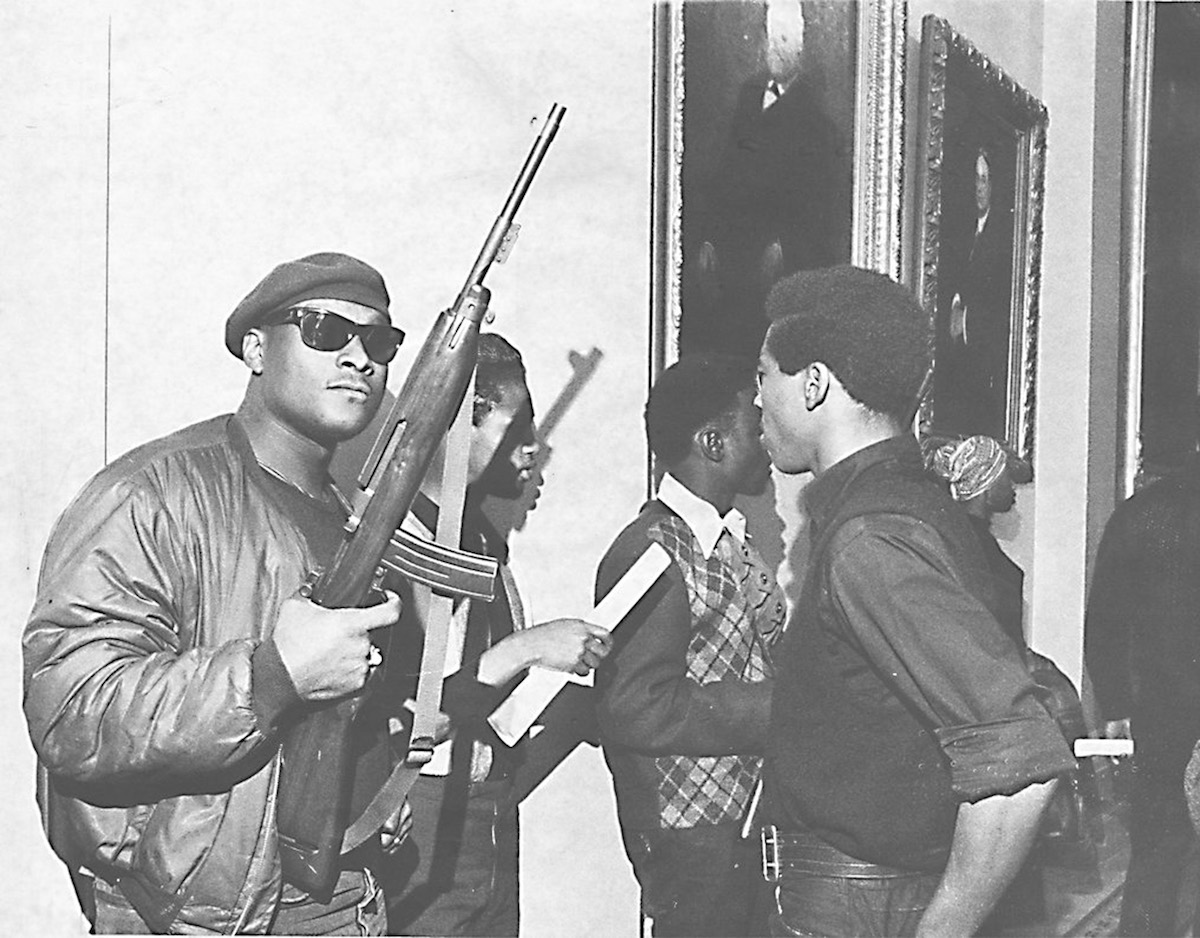

In those days, California was an open-carry state. But, though carrying loaded weapons in public was legal, negroes with guns, to borrow the title of Robert F. Williams’s 1962 autobiography on armed resistance against the Klan, still set the state and the nation’s teeth on edge. In response to this open display of militancy, California passed the Mulford Act, named for its sponsor, Republican Don Mulford, with the support of Governor Ronald Reagan and the NRA.

The debate for individual gun rights was thrust onto the national stage when on May 2, 1967, 30 fully armed members of the Panthers appeared at the California Statehouse in Sacramento to protest the Mulford Act. The Black Panther Party (not the NRA) was at the vanguard for the Second Amendment debate on individual gun rights and pioneered the modern pro-gun movement. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover dubbed the group “the greatest threat to national security.”

For certain, the question of the right of African Americans to bear arms is an old one. No matter which side of the battle over the Second Amendment one agrees with, the effort to ensure that the Constitution applies to each citizen equally is a battle we must all continue to fight—together.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com