The choice black voters face between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton leaves much to be desired. Trump’s recent overtures to African Americans have raised, once again, questions about the relationship between black voters and the Democratic Party. “No group in America,” Trump mused during a speech before a nearly all-white audience in Dimondale, Mich., “has been more harmed by Hillary Clinton’s policies than African Americans.” Noting the Democratic Party’s political dominance in black communities, Trump asked of black Americans, “What do you have to lose by trying something new like Trump?”

Perhaps more than any other voting group in America, black Americans know there is a great deal to lose.

Several polls have shown that only 1% to 2% of African Americans plan to vote for Trump, an all-time low even for a Republican presidential candidate. In the recent NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, only 7% say they will support him. Blacks recognize Trump’s bigotry and, by extension, the bigotry of the Republican Party. A Suffolk University poll found that an astonishing 87% of African Americans believe that Trump is a racist. His latest call for a national “stop and frisk” policy only solidifies that view.

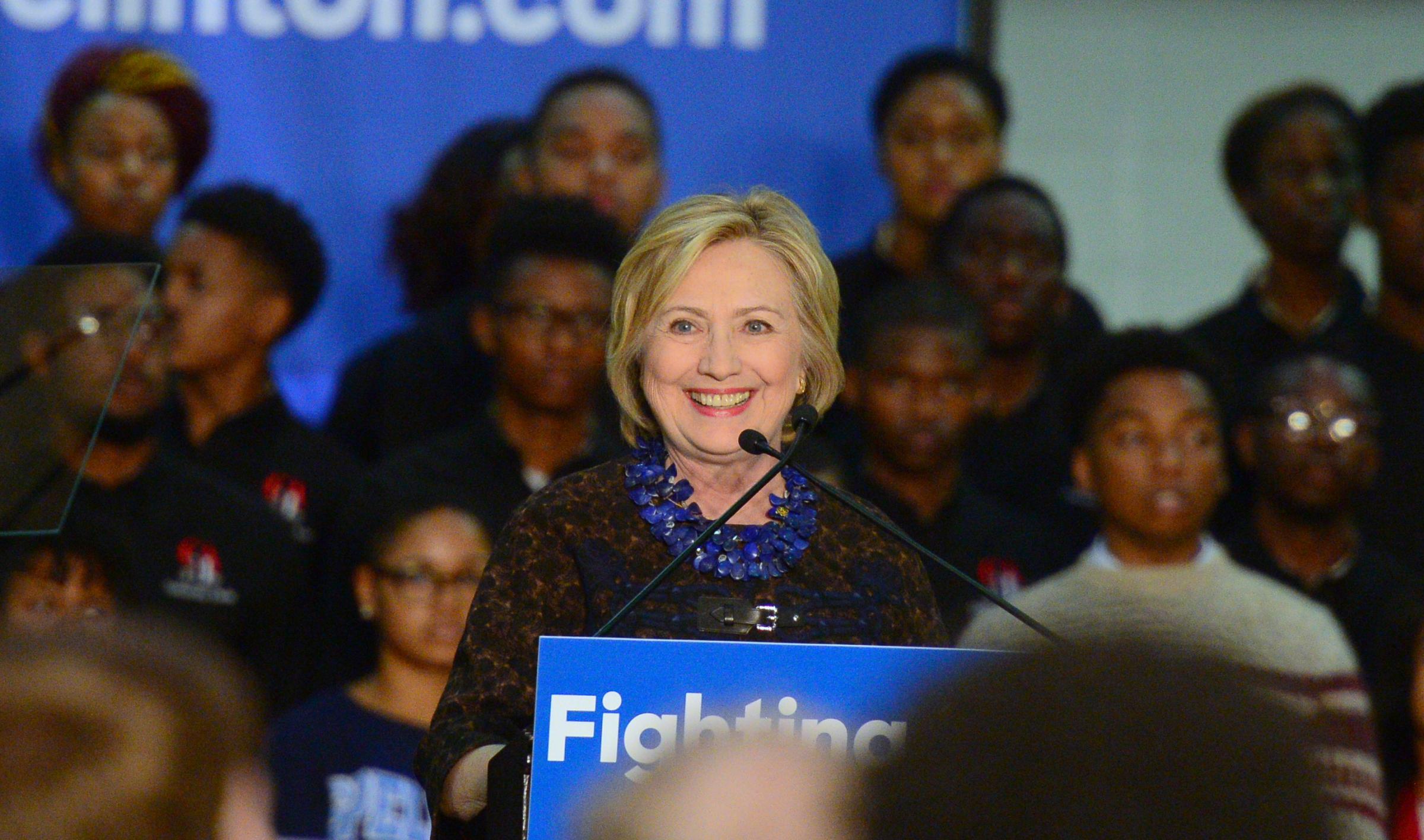

But the issue of black voters’ relationship to Clinton and the Democratic Party is not without concern. Black, brown and poor communities are still living with the legacies of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act and the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (the Welfare Act), two key pieces of legislation backed by President Bill Clinton. The crime measure jump-started the mass incarceration of African Americans and Latinos, and welfare reform pushed hundreds of thousands of poor people from the safety net to the ranks of the desperately working poor. Hillary Clinton, like many Democrats at the time, backed the Crime Bill, labeling poor black and brown youth as “superpredators” who needed to be brought “to heel.” And the NBC/Wall Street Journal poll that showed a lack of excitement among black and Hispanic voters revealed their lingering doubts about her and, perhaps, the party.

The Democrats’ 2016 platform notes how “institutional racism” pervades American life and has called for criminal-justice reform. But the credibility of Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party to follow through on their promises is open to doubt. Recently hacked emails from the Democratic National Committee (DNC) revealed that the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee instructed candidates not to “offer support” for Black Lives Matter’s “concrete policy positions.” Insiders defended the staffer who wrote the memo as someone who aimed to “educate” candidates about the movement. No matter the intent, the memo stoked concerns that the Democratic Party doesn’t really care about black people. Making matters worse, most Americans find Clinton dishonest. In a 2016 CNN poll, only 35% reported believing that the words honest and trustworthy apply to her.

Despite concerns about Clinton and the Democratic Party, black voters have remained loyal. Since 1964, 85% to 95% of African Americans have cast their ballots for the party’s standard bearer. Black votes have been the cogs in the wheel that keeps the Democrats’ electoral coalition churning. Matters need to change, and we have a plan that at once keeps Trump out of the White House and signals to Clinton that business as usual is no longer acceptable.

Despite our deep loyalty, black communities continue to be crushed, even in the face of economic recovery. Jobs remain scarce. Black unemployment is twice that of whites. The Economic Policy Institute reports, “the black-white wage gaps are larger today than they were in 1979.” White households are nearly 13 times richer than African-American ones. Many have lost their homes and now struggle in a brutal rental market. More and more young black families are living in poverty. In fact, 40% of black children languish in poverty.

This election matters. But African Americans can’t engage in politics as usual. Chronically desperate times call for drastic measures. For too long, African-American participation in the democratic process has been distorted. Republicans show little interest in black voters, and Democrats simply take black voters for granted. Political scientist Paul Frymer calls this “electoral capture.” Black voters, he says, “have no choice but to remain in the party. The opposing party does not want the group’s vote, so the group cannot threaten its own party’s leaders with defection.”

Indeed, the Democratic Party has been largely absent in addressing the most pressing issue facing black communities today: criminal justice. (In fact, a glance at Naomi Murakawa’s book The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America actually reveals the party’s complicity in mass incarceration.) A look at the DNC’s 2008 and 2012 platforms reveals how the party has given short shrift to criminal-justice reform. Other than making vague promises to place more police officers on the streets, encouraging DNA testing for death-row inmates and calling for the need to reduce recidivism by investing in “proven community-based law-enforcement programs,” the Democrats’ policy solutions over the past eight years have done little to dismantle the carceral state that they helped create. Had it not been for Black Lives Matter, neither Clinton nor Bernie Sanders would have addressed the need for criminal-justice reform during the presidential primaries.

Despite nearly equal voter turnout—black turnout was slightly less than white turnout in 2008 but exceeded white turnout in 2012, 66% to 64%—the gap between party loyalty and policy output is wide for black voters. A study by the University of Chicago legal scholar Nicholas Stephanopoulos reveals how policy issues preferred by African Americans get low priority. In his analysis of public-opinion data and laws passed at the state and federal levels, Stephanopoulos finds that “as support for policy rises within the black community, the odds of it being achieved actually declined.” It’s sort of like a “black tax” in politics: explicit African-American support for a policy issue is effectively a death sentence for that issue.

THE WRONGS OF HISTORY

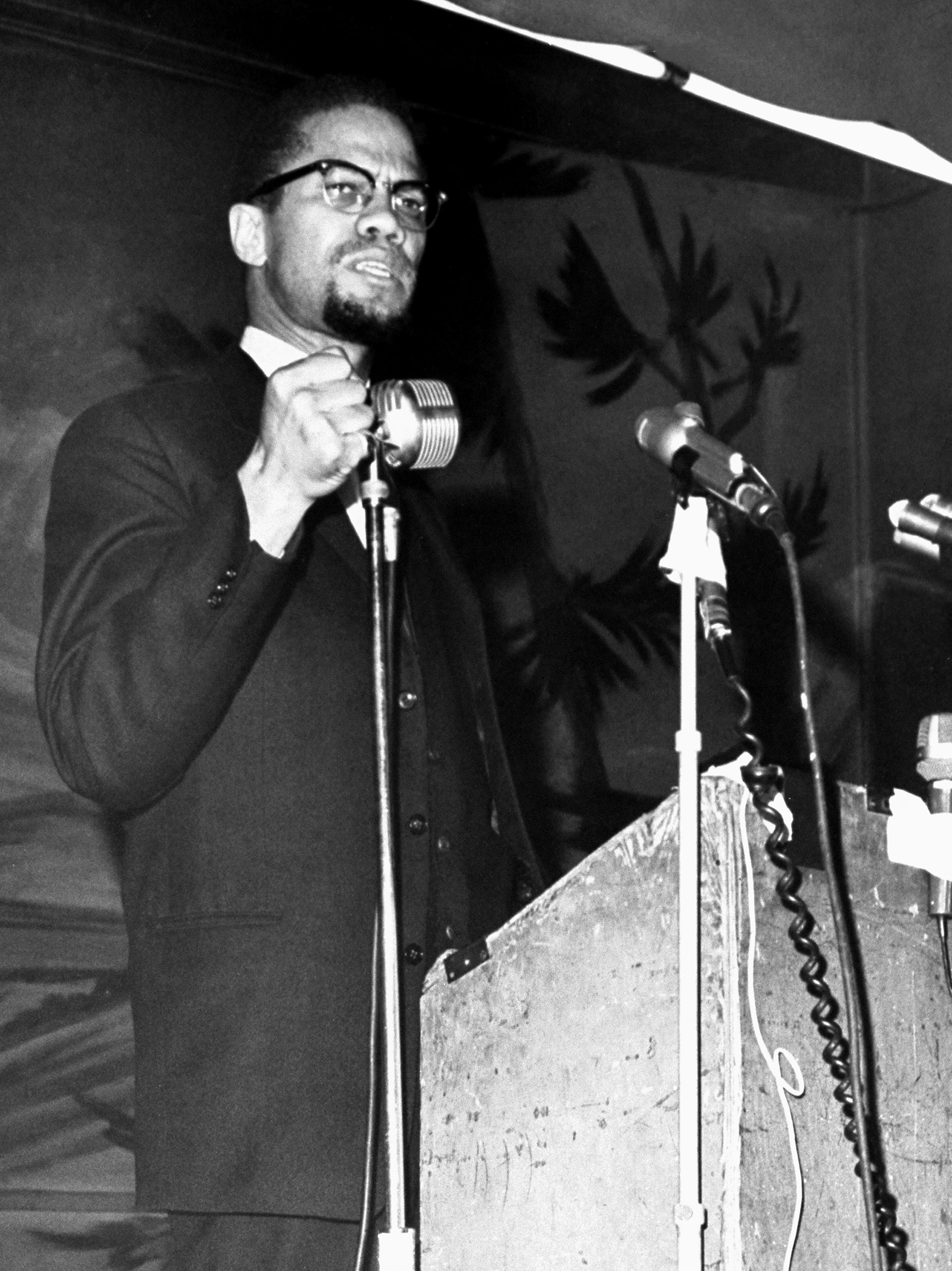

The fact that one political party is the depository of the black vote has troubled black leaders for generations. In 1924 the writer and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson observed that “practically every Negro vote is labeled, sealed, delivered and packed away long before election.” A frustrated Johnson asked, “How can the Negro expect any worthwhile consideration for his vote as long as politicians are always reasonably sure as how it will be cast?” In 1965, Malcolm X implored black voters to abstain from voting altogether if they felt their votes were being cast in vain. The “black man,” he commanded in masculine tones, needed to be “re-educated into the science of politics so he will know what politics is supposed to bring him in return.” “Don’t be throwing out any ballots,” Malcolm instructed. “A ballot is like a bullet. You don’t throw your ballots until you see a target, and if that target is not within your reach, keep your ballot in your pocket.”

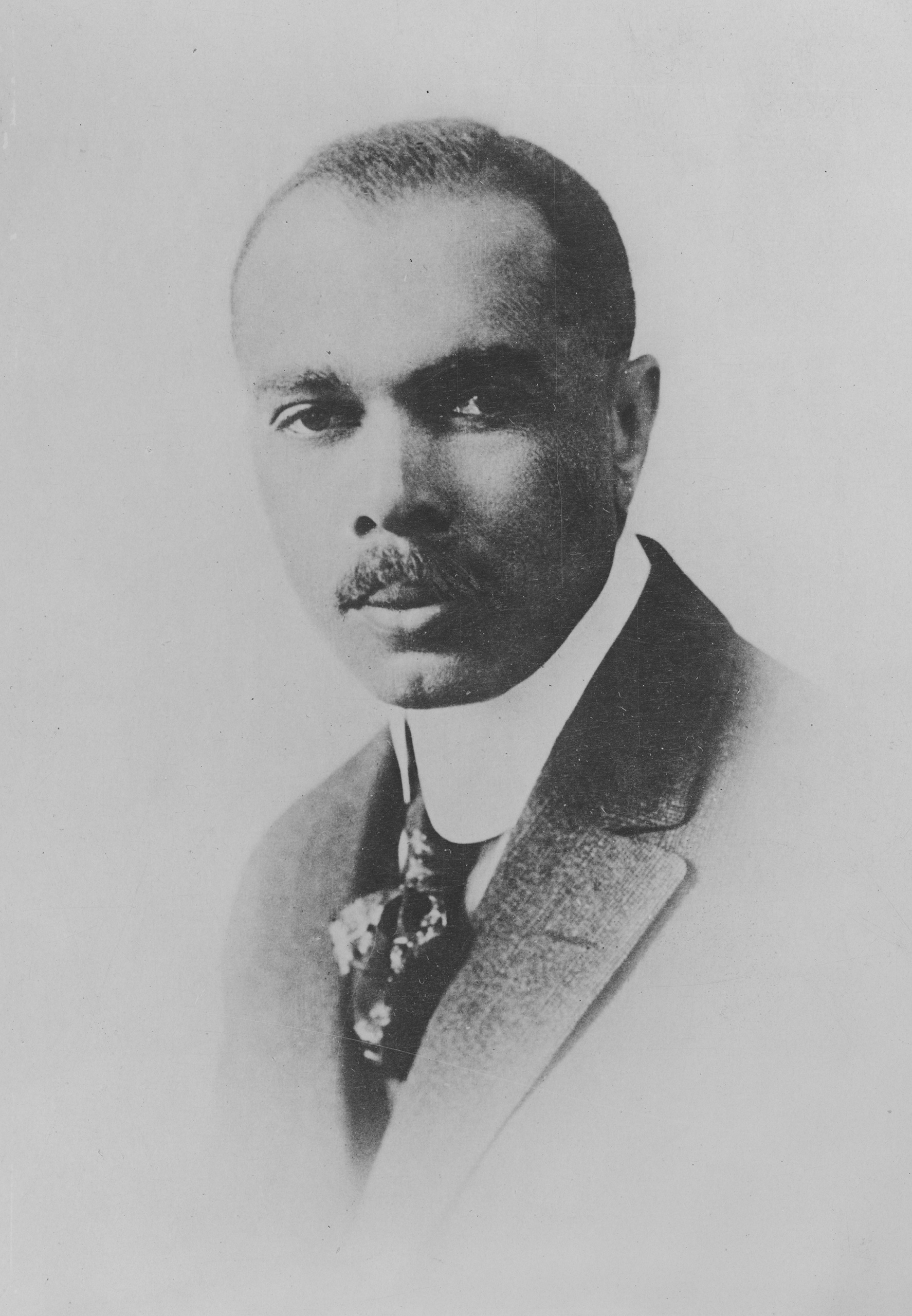

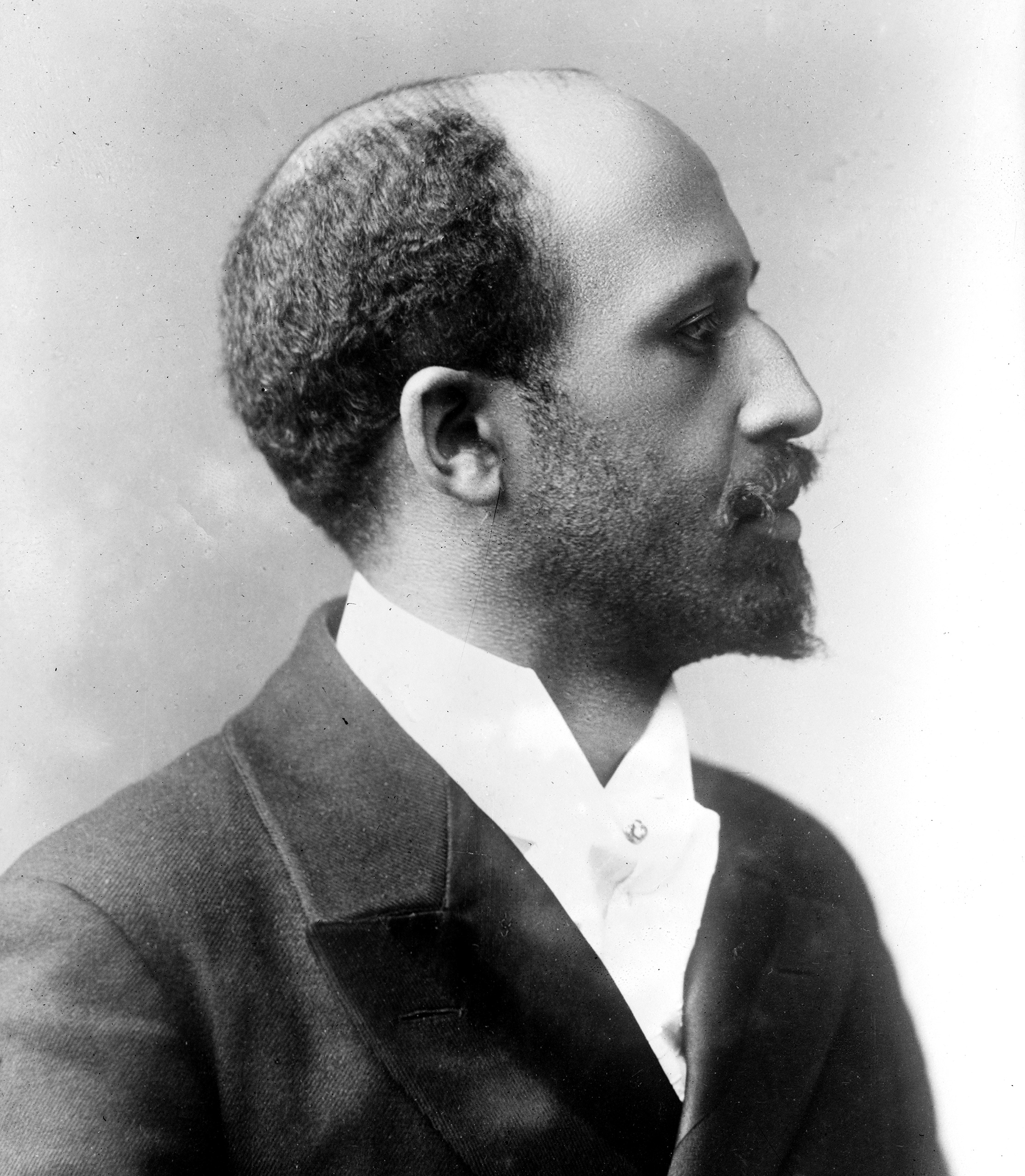

When the Republican Party captured the black vote in the early 20th century, enfranchised blacks were growing weary of having to choose between the lesser of two evils. They had to vote for either the Party of Lincoln, which had abandoned African Americans in Reconstruction’s demise, or the Democratic Party, which was the party of white supremacy in the one-party South. One desperate solution was for blacks to risk voting for the candidate who represented the greater of two evils, in the hope that he would be sympathetic to African Americans because they helped secure the election. In 1912 the civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois endorsed Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson for President and asked black voters to get behind Wilson’s candidacy. Wilson signaled that he would be a different kind of Democrat for blacks. “Should I become President of the United States count upon me for absolute fair dealing for everything by which I could assist in advancing their ‘interests of the race,’” Wilson wrote in a letter to a black minister.

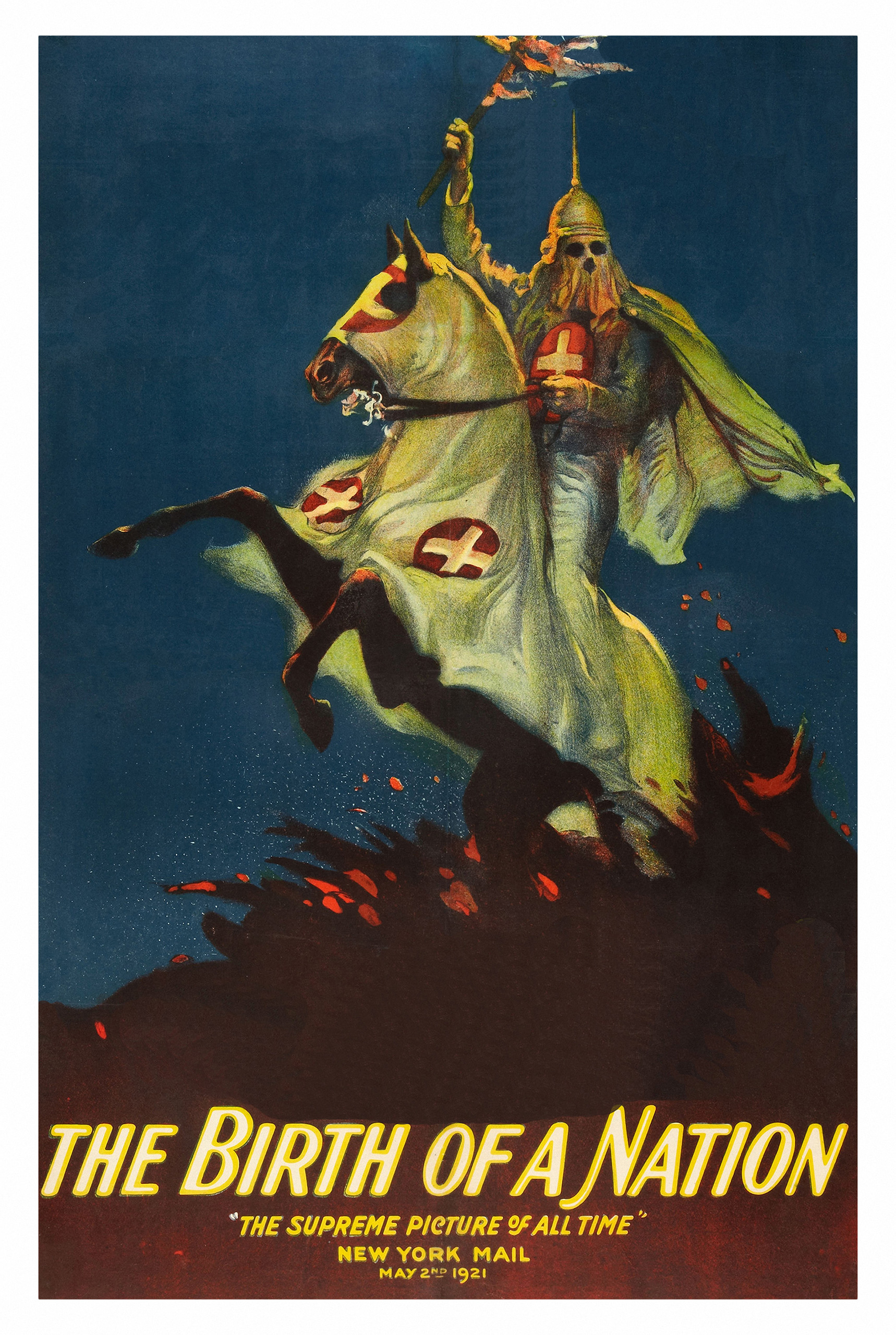

The bulk of black voters remained loyal to the Republican Party, and the endorsement of Wilson from DuBois and other black leaders backfired. After Wilson was elected, he supported the segregation of federal office buildings in the District of Columbia and turned a blind eye to black leaders who met with him to protest lynching and racial segregation. To add insult to injury, Wilson screened The Birth of a Nation—which glorifies the Ku Klux Klan and portrays actors in blackface, among its other racist offenses—in the White House and subsequently praised the film for being “so terribly true.” Jumping ship was a lesson learned for black leaders and voters: it is better to support the party that’s lukewarm to your community’s interests than to risk supporting one that is outright hostile.

Black migration, World War I and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal unlocked the grip of the Republican Party. Black migrants from the South fanned out to cities across the Midwest and Northeast—St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York—in states that happened to be rich in electoral votes. Both parties competed for these new voters, who had been disenfranchised by Southern Democrats.

That created a competition for votes that, along with the New Deal and tepid Republican support for civil rights, gradually moved black voters into the Democratic column. This wasn’t a matter of forgiving the Democratic Party; it was a rational political calculus. As NAACP official Henry Lee Moon explained in his 1948 book on the black vote, “the size, the strategic distribution, and the flexibility of the Negro vote lend it an importance which can no longer be overlooked.” Moon estimated that in 16 states with a total of 278 votes in the Electoral College, “the Negro, in a close election, may hold the balance of power.” In the wake of the closely contested 1948 election, the increased value of the black vote led to policy-focused concessions from Harry Truman and the Democrats. The party included a strong civil rights plank in its convention platform, and Truman issued an Executive Order desegregating the military. Black voters rewarded Truman and the Democratic Party that November, providing him with the pivotal votes he needed in a razor-thin victory over Republican Thomas Dewey.

By the 1950s, civil rights for African Americans were emerging as a consensus issue for both political parties. However, the 1964 presidential election reconfigured the political landscape: the Republican Party positioned itself as the anti-civil-rights party. Barry Goldwater, whose campaign slogan was “In your heart you know he’s right,” opposed the 1964 Voting Rights Act. Lyndon Johnson, pressured by the activism of the freedom movement, commanded congressional Democrats to pass the bill. After Johnson’s landslide victory over Goldwater, Southern white voters began their long exodus from the Democratic Party and African Americans became, once again, captive to one party. To be sure, the passage of the Voting Rights Act increased the numbers of black voters in the South. Since then black voters have provided the margin of victory for Democratic presidential candidates over the years—Jimmy Carter in 1976, Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996, and Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012. In each case, black voters were urged to turn out in large numbers for the Democratic Party, a party that, in the context of governing, would take them for granted.

2016 AND A NEW STRATEGY

We see one way to loosen the hold Democrats have on the black electorate: for African Americans to become strategic voters. We call it the Blank-Out Campaign.

As both pressure voters and pivotal voters, African Americans can simultaneously deliver a victory for the Democratic nominee in swing states and keep the Democrats’ feet to the fire. Casting ballots as pressure voters would not merely be a symbolic act. Depending on the Blank-Out campaign’s success, it could have consequences for Democratic Party leaders down the line. Lower vote totals for the party’s standard bearer in red states could reduce representation of delegates at the 2020 convention, under formulas the party uses to estimate the number of delegates for each state. How well the party’s presidential nominees performed in the preceding two elections is one factor used to calculate the number of delegates for each state. We think the threat of losing delegate representation should incentivize red-state Democrats—and other Democratic leaders—to prioritize issues that directly affect black communities on the state and federal levels.

But at the symbolic level, the Blank-Out Campaign would announce that African Americans are done with business as usual. Party leaders, black and white, would be served notice that black voters are more than cattle chewing cud, to be herded to the polls every two and four years. So how does it work?

Black voters in red states should vote as they usually do for candidates, down the ballot—and leave their choice for President blank. Or they should vote for a third-party candidate of their choice. Either way, red-state black voters—and allies in those states who are committed to social justice—should put their presidential votes to better use than as wasted votes for the Democratic Party. These are pressure voters.

Consider, for instance, the value of voting for a Democratic presidential candidate in Alabama. According to estimates by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, black voters contributed roughly 70% of Obama’s share of the vote in the state, both in 2008 and 2012. But black votes for Obama were inconsequential in preventing Alabama’s nine electoral votes from being delivered to John McCain and Mitt Romney, both of whom defeated Obama in that state with 60% of the vote. By converting “wasted” presidential votes into “none of the above” or support for third-party candidates in Oklahoma, Arizona and other deep red states in the South—the Confederacy, essentially—black voters would exert pressure on party leaders to not take black voters and their issues for granted.

Moreover, it would give grassroots organizations an opportunity to huddle around issues that affect their immediate communities. These organizers would urge black voters not only to participate in the Blank-Out Campaign but also to draw attention to issues that extend beyond the current election cycle. They would then network their efforts with other organizers around the country who are participating in the Blank-Out Campaign.

But our call for African Americans to operate as strategic voters is two-pronged. Not only do we think black voters should abstain from voting for the Democratic presidential nominee in red states, we also think black voters should continue their role as pivotal voters in battleground states. As they enthusiastically did in 2008 and 2012, black voters should turn out in massive numbers this November in states where their votes can determine the margin of victory for the Democratic nominee—Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina and Florida.

While their contributions as pivotal voters have gone largely unacknowledged, Ohio black voters, in particular, have pulled more than their weight for Democratic victories in one of the most highly contested states in the Electoral College. In 2012, Obama won Ohio with a slim 50.1% of the vote, a victory that handed the incumbent 18 electoral votes. Though blacks constitute only 11% of the voting-age population in Ohio, they made up 28% of Obama’s share of the vote in the state. The high levels of black turnout in battleground states that we saw in 2008 and 2012 should be repeated in 2016.

The electoral strategy we are calling for will have to be executed alongside grassroots movements. The Black Lives Matter movement has shown us the power of protest to elevate dormant issues to the political agenda. Indeed, BLM’s success in that regard has put traditional civil rights leaders and organizations to shame. Not only has the Democratic Party captured the black vote, but it appears that the party has captured many civil rights leaders and organizations as well. Many of these leaders and organizations appear to operate as appendages to the Democratic Party rather than as independent advocates. In the past seven years, it has been difficult at times to discern whether they are surrogates for the Obama Administration or nonpartisan guardians of community interests. But rest assured, this November—as they do ritually every four years—civil rights leaders and organizations will by default rally African Americans for the Democratic Party, commanding them to “vote as if your lives depended on it.” And they will be helped along by the policy stances and racist rhetoric of Donald Trump and the Republican Party. The aim is to get us to vote from a place of fear instead of a position of power.

As the Obama presidency winds down, the shallowness of this arrangement has become apparent. Other key Democratic-leaning interest groups were knocking at the President’s door with agenda items for him to act on after he was elected in 2008 and re-elected in 2012. Yet it took a coalition of civil rights organizations—headed by Al Sharpton of the National Action Network, Marc Morial of the National Urban League, Ben Jealous, then president of the NAACP, and Melanie Campbell of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation—four years and nine months to deliver an agenda for black America to Obama. BLM has done more in two years to elevate the need for criminal-justice reform than a two‐term black Democrat in the White House, civil rights leaders, the more than 40 black members of Congress and the scores of black delegates and party leaders at the 2008 and 2012 Democratic Conventions combined.

The Blank-Out Campaign would get us to see beyond the elections themselves and send a clear message to Clinton. She will not win the White House with the traditional politics of the Democratic Party. The Blank-Out Campaign would disrupt the idea that democracy rests primarily in putting someone in office, and allow us to reject the game that both political parties play with black votes. No more games. Too much is at stake. Black voters, and American voters in general, must take back our democracy, and this requires dramatic action. If what we call for seems drastic, it is because the political choices African-American voters have before them have grown so dire.

Glaude is the chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University and the author of Democracy in Black.

Harris is the director of the Center on African-American Politics and Society at Columbia University and the author of The Price of the Ticket.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com