Although the Venice Film Festival ends on September 10, my time here is drawing to a close. The Festival has made several physical additions this year, chief among them a new theater structure, the Sala Giardino, which is open to the public—and better yet, all screenings held there are either free or cost only 3 euros. The Venice Film festival is a public one—in other words, it’s not just for professionals, and movie lovers have always been able to purchase tickets to the public screenings of all films. But the Giardino, with its low- or no-cost ticketing structure, is something new, a democratic and civic-minded enterprise. And considering the theater was packed full at the evening and weekend screenings in particular, it appears to be a success. Film festivals that are open to the public—as Toronto is, for example, and as Cannes is not—are special creatures, and in a world where plenty of people are happy to stay at home and watch stuff on Netflix, it’s heartening to see so many venturing out to watch a film on the big screen, together. The day I stop believing in the power of that communal experience is the day I’ll know it’s all over.

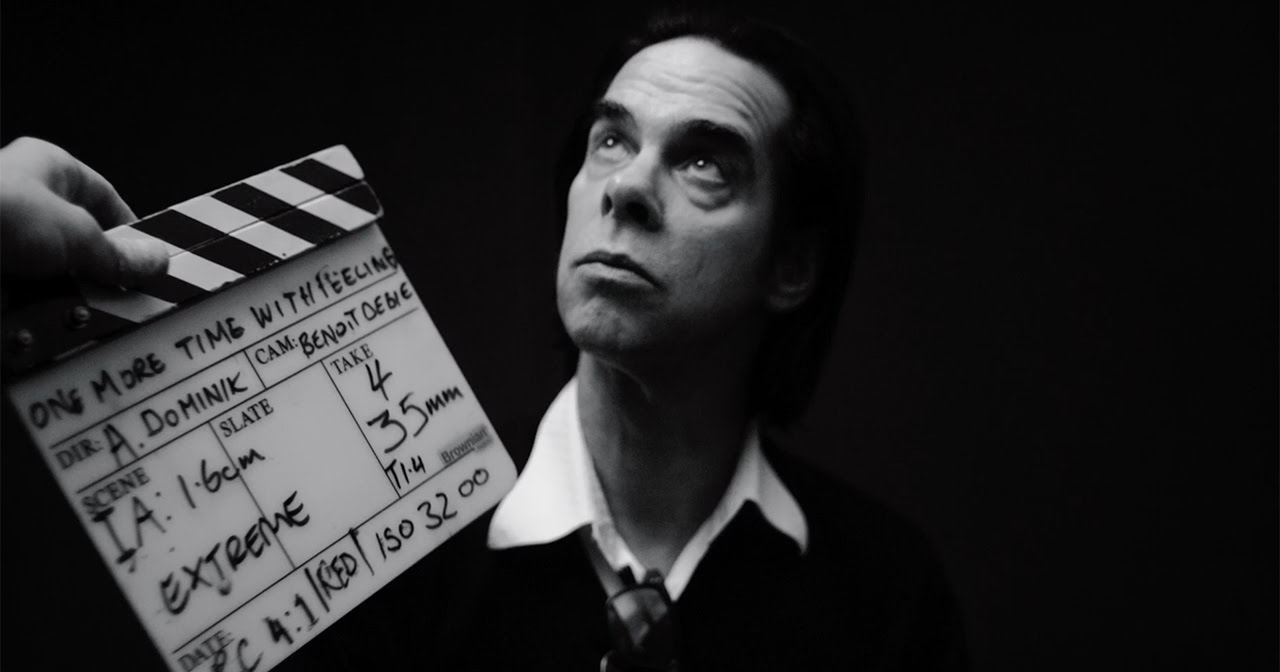

Because to see a movie with an audience is, sometimes, to be haunted together. Of all the films I’ve seen in the eight days I’ve spent here, the one I can’t get out of my head is Andrew Dominik’s One More Time with Feeling, a documentary shot in 3-D black-and-white that follows Nick Cave as he records the 16th Bad Seeds album (to be released on September 9), Skeleton Tree. But the circumstances of this making-of documentary are specific and tragic: In July 2015, Cave’s 15-year-old son, Arthur, died after plunging off the side of a cliff in Brighton, England. The album was partially completed at the time at the time of his death. Cave realized that after he finished it, he would have to promote it. So he approached his friend Dominik to make the documentary, as a way of avoiding having to talk to the press about his son’s death. The resulting film is both gentle and staggering, an examination of the way our personal experiences can spur creativity—or render it inconsequential.

Dominik’s camera follows Cave—along with some of his cohorts, like longtime collaborator Warren Ellis—as he does relatively mundane things, like re-record vocals that didn’t quite gel the first time, and unspeakable things, like try to explain how the trauma of losing his son made it harder to write songs, not easier. As the movie begins, the tragedy is alluded to but not mentioned outright—in fact, I suspect many viewers may have nearly forgotten that it happened, not out of callousness, but perhaps because when artists we love suffer a loss like this one, the kindest thing is to turn away. What can we do, after all? It’s only right to allow public figures—rock stars, actors, politicians, anyone—the privacy of their grief.

Mostly, Cave and his wife, Susie Bick, who also appears in the film, talk around Arthur rather than about him: It seems they’re balanced on a thread between heightened awareness and permanent numbness. Cave speaks somberly about his inability to think, let alone talk, about the days around the time Arthur died. “Time is elastic,” he says, “We can go away from the event but at some point the elastic snaps back and we always come back to it.” At one point Dominik’s lens scrutinizes Cave’s face, currently that of a tired, ancient boy, as if he were showing it to us for the first time. In fact, it’s as if Cave is seeing it for the first time. “What happened to my face?” he says. “Look at these bags under my eyes. Where did they come from? They weren’t here last year.”

Even if it makes sense that One More Time with Feeling is in black-and-white—Cave is surely a black-and-white kind of guy, a Daguerreotype in motion—you may be wondering why the picture was shot in 3-D. But the effect works, drawing us in close in a kind of whispering intimacy, while marking a line that we absolutely cannot cross. 3-D makes you think you can reach out and touch an image, or a person, but really, we’re kept at a safe and respectful remove. It’s not easy to watch artists we care about suffering, even suffering quietly and guardedly, as Cave and Bick do. But by sharing something of themselves with us in this movie, these grieving parents give us something that goes beyond art. There’s only so much you can put in a song. The rest is in Cave’s eyes.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com