On the rainy Tuesday morning after Hong Kong’s legislative elections, Nathan Law’s office looked something like a slumber party in a fallout shelter. Two members of his political party, Demosistō, were curled up asleep on battered futons, and crossing the room meant tripping through a minefield of campaign detritus: bullhorns, empty Pocari Sweat bottles, extension cords, a ladder propped against a mountain of cardboard boxes. One campaign member had hung his laundry from the metal grid of the drop tile ceiling and forgotten it there.

“We let things get messy during the election,” Law grins.

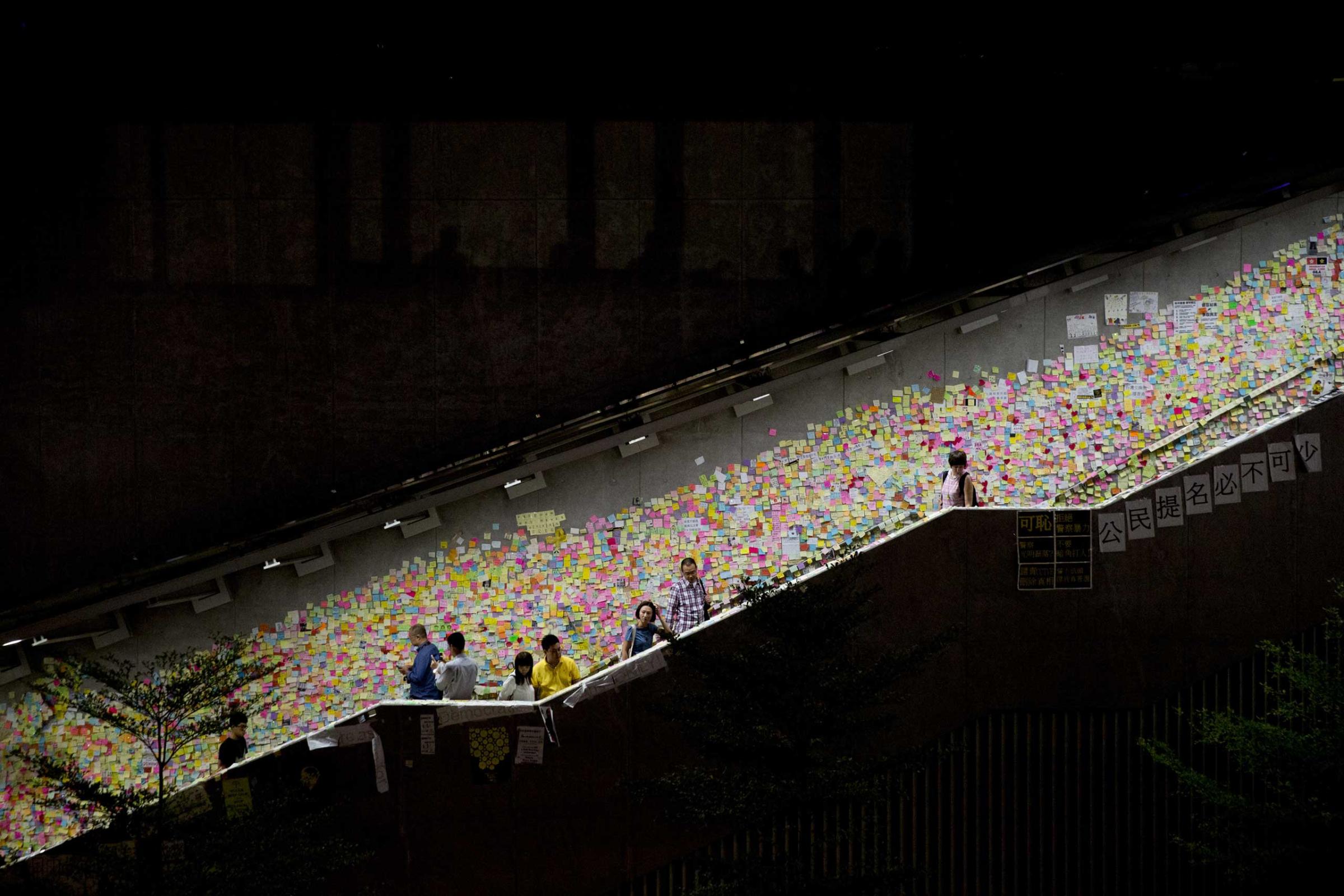

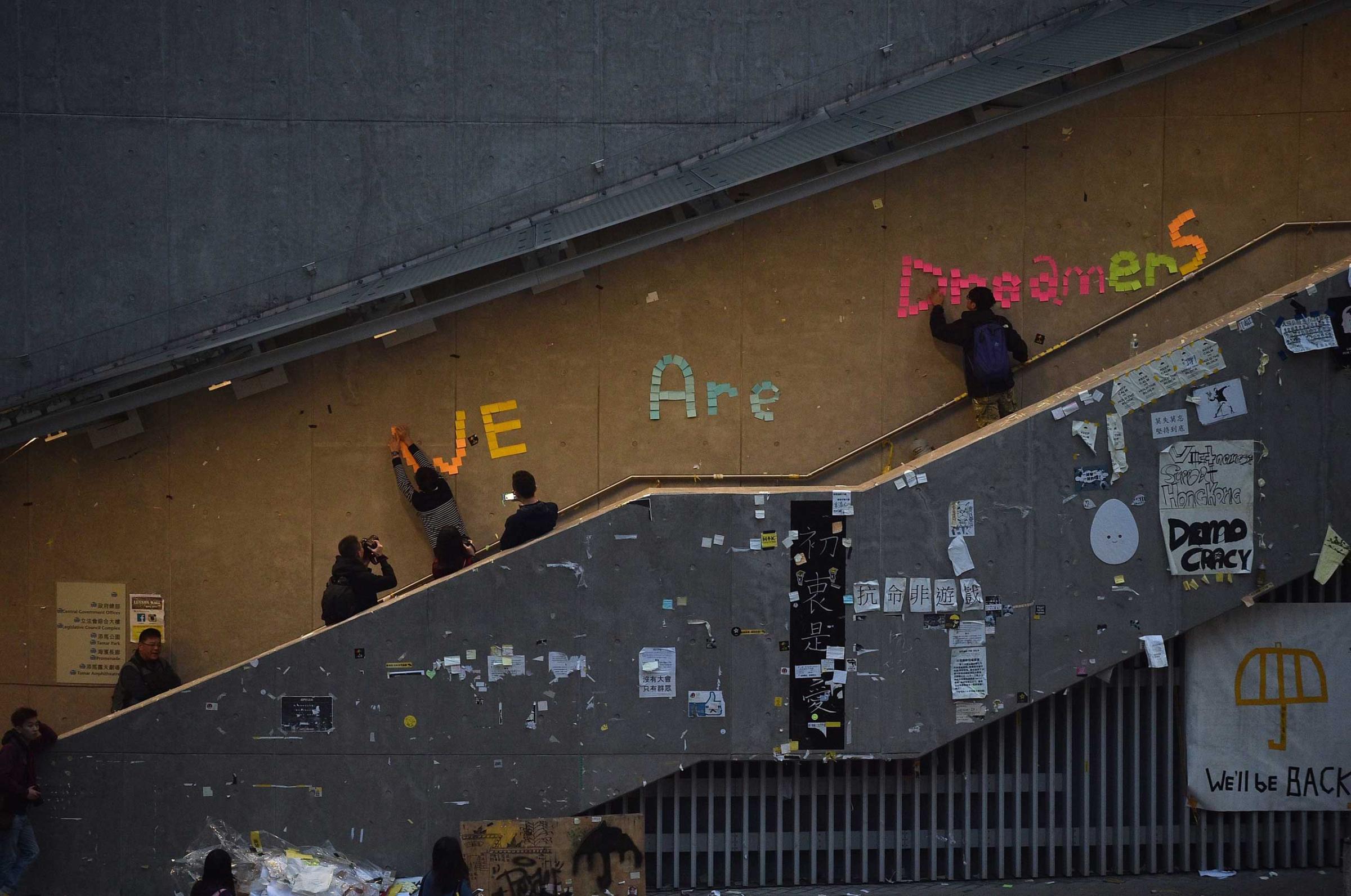

And if he is fazed by the result of that election — in which he, at 23, became the youngest lawmaker in Hong Kong’s history — he’s adept by now at affecting grace under pressure. He’s had two years to acclimatize to the political spotlight, ever since he emerged as a leader of the massive pro-democracy demonstrations, collectively known as Occupy Central or the Umbrella Revolution, that floored Hong Kong for three months in the fall of 2014. He’s grown up since then — his wardrobe is chicer, his jawline a little more pronounced — while Hong Kong has grown more anxious, neutered in the face of what it sees as Beijing’s encroachment on the semiautonomous territory.

“People have put their trust in me, and now I have to perform,” he says. “We hope that we can bring the issue of Hong Kong’s future to the parliamentary table. That’s completely different to protesting.”

Law is one of a handful of young pro-democracy activists who earned seats in Sunday’s elections — an unprecedented feat in this town of career politicians, and indicative of a widespread urge for political change that has been mounting since the 2014 protests. Then, demonstrators demanded the right to directly elect Hong Kong’s leader, the chief executive, who is chosen by a council seen as Beijing’s proxy — one of several constitutional mechanisms intended to ensure that the central government has the final word when it comes to managing the territory, which has otherwise nominally held a “high degree of autonomy” since the British returned it to China in 1997.

The call for reform went unanswered, and the protest leaders were dismissed by critics as hapless, unschooled fringe ideologues who ultimately lacked real political power. Sunday’s elections have invalidated this. Law earned more than 50,000 votes, the second highest of any candidate in his constituency Hong Kong Island, which is allotted six seats in the legislature.

“It shows that Hong Kong people want changes in the democratic movement,” Law says of his victory. “Hong Kong’s democratic movement has been stuck in a place where it can’t escape from the road map drawn by the Communist Party.”

His zeal for democratizing Hong Kong is the passion of a convert. He was born in Shenzhen, the mainland metropolis just north of Hong Kong’s border, to what he calls a “blue collar” family; they moved to Hong Kong in 1999, when he was 6. His parents enrolled him in schools run by Beijing sympathizers. Law recalls an October morning in 2010 when his principal stood up at a morning assembly to denounce Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, who had just won the Nobel Peace Prize for “his long and nonviolent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” (Liu currently sits in prison for “subverting state power,” slated for release in 2020.) There were lessons in Chinese politics — which were presented as “uncorrupt and democratic,” even though Law saw nothing on school field trips to the mainland that could compare with Hong Kong’s rule of law.

An independent judiciary is something Hong Kong’s democracy supporters regularly point to (with alternating pride and worry) as a vital distinguishing factor between the semiautonomous territory and the rest of China. On paper, Hong Kong’s freedoms are preserved by the constitutional dynamic known as “one country, two systems,” designed to bulwark the city’s freewheeling ways even as it acknowledged China’s sovereignty. The fear now is that it is not enough. The demonstrations in 2014 were a call for election reforms, but more essentially they channeled an existential angst over what many saw as China’s incursion into the territory’s way of life. (The chief executive, whose method of appointment protesters were seeking to alter, is widely seen as Beijing’s lieutenant.)

Law was a figurehead of the protests, in large part because he was one of three student activists arrested for storming a public square near the government headquarters on Sept. 26, 2014, which proved to be a watershed night for unrest. The two others were Alex Chow and then 17-year-old Joshua Wong, the gawky, bespectacled activist who emerged as a poster boy for Hong Kong’s democratic movement. Today, Wong — at 19, still too young to run for public office — is the secretary general of Demosistō, the political party Law heads, which emerged from the ashes of the Occupy movement. Wong is a foil of sorts to Law: he is vociferous, occasionally to the point of theater; Law is more measured, with the pensive, scholastic look of a graduate student. (Never mind that he hasn’t yet graduated from college. Schoolwork took a backseat to politics for awhile.)

“It’s amazing. We’ve created a miracle in Hong Kong,” Wong says at campaign headquarters the Tuesday morning after the elections. He had two hours of sleep the night before. “People want change. Don’t think that young people can’t be a force of change.”

But for all their lyrical rhetoric, Law and his colleagues are not Hong Kong’s new radicals. The popular anxiety that enabled their political rise also fostered a more extreme movement — a crusade for Hong Kong’s outright independence from China. It is an implausible solution, but it has Beijing anxious: last month, a number of pro-independence candidates were banned from running in the Legislative Council elections on the grounds that their platform was unconstitutional.

“For now, our final goal is a city with high autonomy, a fair political system, and social justice,” Law says. “This vision is superior to independence, because it relates to how we live together as a society. No one can guarantee that independence would resolve certain issues with the local establishment.”

He hopes that Hong Kong people will eventually have a referendum determining their future, but concedes that it’s a “target that’s still far away.” His short-term goals are things like local agriculture incentives and water-purification facilities, all of which will reduce Hong Kong’s dependency on the hard resources of mainland China.

It will be interesting to see if he plays well with others. He does not have a massive amount of respect for the more traditional pro-democracy lawmakers in the Legislative Council, whom he sees as hamstrung. “They cared too much about getting votes,” he says frankly. “They were afraid to provide a political vision and talk bluntly about the real issues.” (He’s not alone in feeling this way: four veteran democrats were voted out in Sunday’s elections.)

Nor does he see himself as the liaison between the new democratic movement and the pro-Beijing camp, which will continue to hold the legislative majority — 40 seats to the democrats’ 30, in large part because of the curious nature of the Legislative Council elections, which allows half of all seats to be elected by representatives from various economic sectors and professions (a system seen as favorable to Beijing). In the legislature, he will be serving alongside fellow freshman lawmaker Junius Ho, a pro-Beijing figure who has openly called for Law to receive a harsher sentence for his storming of Civic Square in 2014.

“I don’t know their attitude, and I don’t really care, to be honest,” Law says of the pro-Beijing camp. “They’re the ones abusing Hong Kong people, so I don’t think there’s room for cooperation with them.”

The election of young protest leaders to the Legislative Council is only the latest referendum on how Hong Kong feels about its sovereign overlords in Beijing; in a recent survey conducted by the University of Hong Kong, less than half of those polled said they had faith in Hong Kong’s future. (A startling 1 in 6 is on board with the idea of the territory’s independence, and 40% of the 15-to-24 age group say they are.)

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

Those who derided the failure of the Umbrella Movement to deliver tactile policy results are now left to answer to a new political tide that is rising because Beijing and the local establishment declined to take its earlier and more modest demands seriously.

“The new political movement is effectively the creation of C.Y. Leung and Beijing,” the China expert Willy Lam says, using the initials of the current Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying. “Five or six years ago, most young people in Hong Kong were apathetic about their political future. But now there’s been no political progress, and 2047 [when ‘one country, two systems’ is scheduled to expire] is not that far away.”

Experts are now waiting to see how Beijing reacts to the results of the elections, which many have linked to the rampant distrust of Leung. Law professor and Occupy Hong Kong initiator Benny Tai ventures that the elections will be the “determining factor” in whether Leung is chosen for a second term in next March’s election.

“Beijing will have to re-evaluate, since it appears they’ve lost the ability to govern Hong Kong,” Tai says. “Replacing an unpopular leader with a highly popular one is a strategy Beijing likes.”

Law and his political compatriots are eyeing next March’s chief-executive election — Wong says that it may occasion further protests — but in the meantime they are more concerned with weathering Law’s transition from outspoken activist to formal politician. Wong is currently in the process of finding the party a new office on Hong Kong Island, near the government headquarters, while Law, a 23-year-old who grew up in public housing, will now be making nearly $144,000 a year, plus perks. He will not wear a tie to work.

“I’ll dress like a young person,” he shrugs. “I am a young person.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com