An entire section of the visitors’ guide to the Holy Mountain of Athos is devoted to the subject of photography, and to summarize the gist of it – there are no pictures allowed. We learned about this a bit late in our trip. Yuri Kozyrev, TIME’s contract photographer, had already flown from Moscow to meet the rest of our trio in northern Greece. Otis, our Greek translator, had come from Athens. I had come from Berlin. And a few days later, Russian President Vladimir Putin was due to arrive on the Holy Mountain for a pilgrimage.

Photographing his visit to one of the most sacred sites in Orthodox Christianity was a pretty important part of our assignment. So Yuri groaned as Otis translated the rules – no swimming, no sunbathing, no shorts, no photography, and on it went. This was at the end of May, and we were standing near the spot where the border of Mount Athos is marked with a wall of stone. “Forbidden entry for all,” said the sign on the other side of it. “Violators will be prosecuted fully to the extent of the law.”

We started to question our chances. Mount Athos – or, as it is officially called, the Autonomous Monastic State of the Holy Mountain – is a spit of land about five times the size of Manhattan that juts out of northern Greece into the Aegean Sea. For roughly the past thousand years, it has been governed by a council of Orthodox monks, and as the name of their microstate suggests, they enjoy a great deal of autonomy from the rest of Greece. Under Article 105 of the Greek constitution, the monks are guaranteed the “ancient privileged status” of self-governance, and they alone can decide who enters Mount Athos.

On this point their rules are especially strict. No women are permitted to visit. Female animals are also banned, with the occasional exception of cats and songbirds, which are too difficult to keep away. The formal reason for such rules is the same as the reason for the monks’ vows of celibacy: they must remain faithful only to the Virgin Mary, who they believe received Mount Athos as a gift from Christ to use as a private garden. As Article 105 of the Greek constitution further stipulates, “Heterodox or schismatic persons” – in other words, non-believers – are forbidden from living there. Men not baptized into the Orthodox faith are discouraged from even visiting, as we learned upon presenting our documents at the Athos pilgrimage office.

This bureaucratic oddity, unique within the European Union and possibly throughout the world, consisted of a basement room in the Greek village of Ouranoupolis, which borders Mount Athos to the north. Apart from the Orthodox icons hanging on the walls, it resembled the waiting area of a provincial police station, complete with a glass partition between the monastic bureaucrats and the applicants. Upon seeing my U.S. passport, the men behind the glass began loudly debating something in Greek before handing the document to their superior, who looked me up and down.

“What is your religion,” the man said. On my mother’s side, there is some Russian Orthodox blood, and in my passport my place of birth is listed as Russia, the most populous Orthodox country in the world. This was apparently enough to earn me a diamonitirion, the visitor’s permit that comes stamped with an image of the Virgin Mary. (Yuri and Otis, who are bona fide Orthodox Christians, were more readily admitted.)

But we still had no permission to photograph much of anything, and the Kremlin seemed unwilling to help. Over the phone, its press office had explained that this visit would be a personal one for Putin – more spiritual than political – so they would not be organizing the type of press pool that normally accompanies the President on his travels. “If you manage to get there,” the spokesman said, as if issuing a challenge, “we’ll see what we can do for you.”

Read next: Putin Aide Vladislav Surkov Defied E.U. Sanctions to Make Pilgrimage to Greece

We got there two days early. From the port of Daphne, where our ferry came ashore, we pushed our way onto a bus full of pilgrims, priests and monks from all around southern and eastern Europe, mostly Greeks, Russians, Bulgarians and Serbs. A lot of them seemed as confused as we were upon reaching the ancient city of Karyes, the capital of the Holy Mountain.

It is a tiny hamlet, consisting of a bus station, a medieval church and a few administrative buildings, along with a few cafes and souvenir shops, where T-shirts printed with Putin’s face were on sale next to rosary beads and icons of Orthodox saints. The shopkeeper said the shirts were selling briskly, and he advised us on how to reach the place where we were staying.

Over the next four days we met dozens of monks on Mount Athos, and apart from the fact that they have beards and dress in black, it is difficult to generalize about them. Like any large community of people, they come in all types, including a fair share of zealots. Some were narrow-minded or even hateful in their opinions of the sinners of the outside world. But as a proportion of the population, there did seem to be an unusual number of men on Mount Athos who gave the impression of profound serenity and perceptiveness, as though they were able to guess your thoughts before you said a word. Our host, Father Makarios, is one of these.

Thin almost to the point of emaciation, he greeted us at the entrance of his cell dressed in a sun-bleached black robe that was coming loose at the seams. In case it isn’t clear by now, my views on organized religion lean heavily toward skepticism, and Mount Athos did not bring about my conversion. But when Makarios came over to shake my hand, something strange did happen. For a long moment my mind went blank, and instead of my name I could only remember to mumble something that sounded like “salmon.” He took this with a smile and showed us inside.

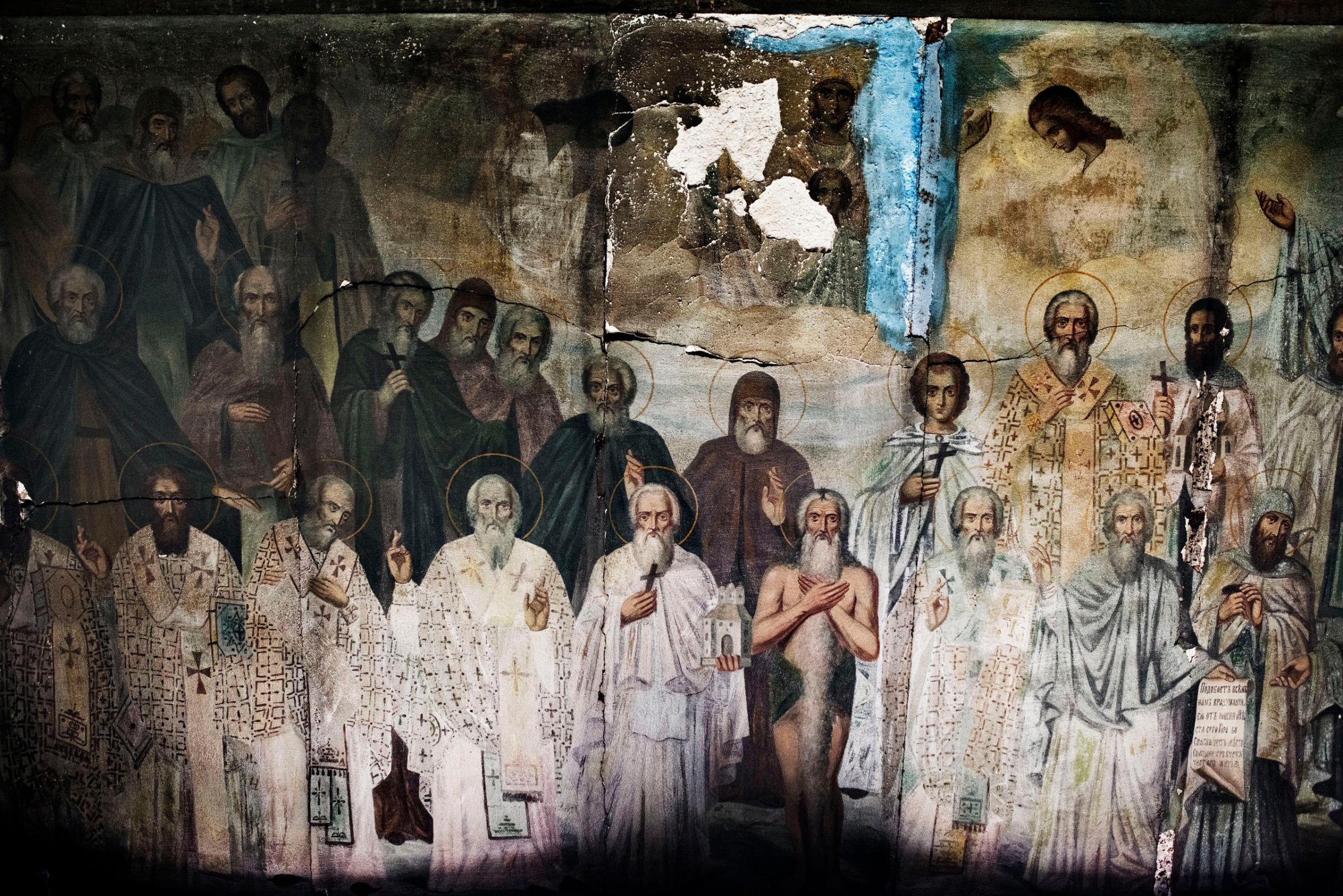

Around a shaded courtyard, his cell, or kellia, included a complex of stone and wooden houses with a tiny church near the entrance and, in the back, a large dining hall, its walls covered with frescoes of Orthodox saints. On one of the tables he had set a typical meal: boiled potatoes and green beans, bread, water and an unfamiliar type of leafy green that tasted a bit like pine. Then he left us alone to eat and plan out the rest of the trip.

Getting around would be the hard part. There are 20 monasteries on Mount Athos – 17 of them Greek, one Bulgarian, one Serbian and one Russian, each representing one of the traditional centers of the Orthodox faith. By foot, all of them take hours to reach along the trails that wind through the mountains. So keeping up with Putin’s entourage would require a car. But taxis on Mount Athos are in very short supply, and the buses to most of the monasteries usually run once a day. After sundown, the monks shut their gates, and no one is allowed to come or go.

Our savior came in the shape of a corpulent monk named Father Ioannikiy, who owns an old pick-up truck and was willing to take us around for about $100 an hour. We had no choice but to accept. Along the gravelly roads and sheer cliffs of the mountain it took us about an hour to reach the Russian monastery of St. Panteleimon the next day, as preparations for Putin’s visit were winding down. Dozens of Russian security agents were staying in the guesthouses, and a few of them had even put on wetsuits to go diving in search of threats to the President’s boat.

Outside the main gate, we sidled up to a group of reporters from a Russian TV channel and joined their tour of the grounds. The first stop was called the kostnitsa, or “bone room,” whose walls were lined from floor to ceiling with human skulls. On their foreheads, many of them had been inscribed with the names of monks and the years when they had died, some dating back several centuries.

One of the monks pointed out the skulls marked with the date of 1913, a tragic year for St. Panteleimon. That summer, several ships of the Russian Imperial Navy came to suppress a theological rebellion among the monks, whose teachings the Russian Orthodox Church had deemed heretical. After failing to convince them to change their views on the nature of God, a Russian bishop allowed the czar’s troops to storm the monastery. Hundreds of the Russian monks were taken prisoner and brought back to the Russian Empire to be punished for their heresy.

Unsurprisingly, our request to photograph the bone room was denied. So were Yuri’s attempts to photograph the courtyards of St. Panteleimon and its dining hall. It was mostly by chance that he managed to shoot inside the ancient Greek monastery of Vatopedi near the end of our trip. As we pulled up to its gates around dawn one morning, they swung open and a large procession of monks emerged, carrying an icon of the Virgin Mary that was shielded from the sun with an elaborate parasol. We later learned that this ceremony takes place only a few times a year, and there were so many pilgrims filming it on their smartphones that the rules against photography seemed impossible to enforce. Eventually the monks relented.

Read next: Russia’s President Putin Casts Himself as Protector of the Faith

With Putin we got nearly as lucky. On the day of his arrival, many of the roads around Athos were closed to allow his cortege to pass, and several cordons of security were set up around St. Panteleimon. The first two were manned by Greek police, and Otis somehow convinced them to let us pass. But at the final gate a Russian soldier dressed in camouflage instructed us to leave; it was, he said, a private event.

Putin had not yet arrived. On his way to the Russian monastery, his black Mercedes SUV had made a stop in Karyes, the capital, for a ceremony with the governing monks. We got there just in time to see him climbing the marble staircase into their administrative headquarters. The scene was hectic. Snipers were positioned on the roof of the building. Dozens of Kremlin security agents were milling around in shiny suits, sweating and struggling to control the crowd of black-robed monks and foreign dignitaries. Inside the conference room with Putin, a pair of waiters brought two silver trays loaded with shots of tsipuro, the liquor that the monks of Athos excel at brewing themselves.

But the President declined the drink. He looked bored and restless in his chair beneath an icon of the Virgin, as though eager to get through the Greek monks’ speeches and move on to the Russian monastery. A few hours later he was gone, having spent only half a day on the peninsula, and we headed over to the only restaurant on Athos for a meal of bean soup and tsipuro.

At the table behind us a group of six Russian pilgrims were just making a toast when a man came in to sell some holy oil. With the timbre of a carnival barker, he listed the bones of the saints that had been used to bless his bottles of oil. “I’ve got the left foot of St. Ana,” he said. “I’ve got the head of St. Prokofiy. I’ve got the right hand of Ioann the Theologian.” There weren’t any takers.

By the time we got back to Makarios’s house the sun was already setting. On the benches in his courtyard a few Greek pilgrims were sitting around and watching clips of Putin’s visit on their phones. As recently as a decade ago even radios were officially forbidden on Mount Athos. Electricity was scarce back then, and the bigger monasteries only had a few landline phones for everyone to share. Now most of the cells have Wi-Fi, and many of the monks keep iPhones tucked into the pockets of their robes.

When it got too dark to sit in the courtyard, Makarios invited a few of us into his library, where the table was set with glasses and a bottle of schnapps from the night before. Instead of a blessing or a prayer, he went around the room, grabbed each of us by the head and, with a quick twist, cracked the bones in our necks to let out the stress. It was a trick he used to shatter people’s preconceptions of how a monk is supposed to behave.

Sitting down, he mentioned that he’d come to Athos as a teenager, hoping to “live a solitary life.” That was 48 years ago. He is now 65. And his life is hardly solitary. Whether it’s pilgrims, reporters, smartphones or foreign heads of state, the outside world has a way of intruding on Athos, no matter how many walls and rules the monks create to keep themselves secluded. I asked if that bothers Makarios. “Nothing bothers me,” he said with a smile. “Nothing.” Yuri was welcome to take his picture.

Yuri Kozyrev is a TIME contract photographer represented by NOOR.

Alice Gabriner, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s International Photo Editor.

Simon Shuster is a TIME correspondent based in Berlin.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com